EDITOR’S NOTE: Full disclosure — I’ve been in friendly contact with Stephen Turnbull for a number of years and VintageNinja was a quoted and cited source for this new book.

During the 1980s ninja boom one’s shelf was packed with a variety of books on the subject, from seemingly legit self-defense manuals based on generations old hand-to-hand combat, to less…er…responsible…guides to hypnotic mind powers and secret death cult rituals. There were books that explored a little feudal history, a few fiction tomes set in what we assumed was a realistically portrayed past, and manuals for making shadow-tools based on the scribblings of the ancients.

As wide-ranging as that all seems, the English-language writings of the time had one major thing in common — they were coming from the martial arts world and were produced by people in the business of martial arts training. Determining whether or not these authors and publishing houses were legitimate curators of ancient secret scrolls or cash-grabbing charlatans was like negotiating a storm at sea in the dark, and regardless of legitimacy of source, the fact that these texts were coming from martial arts standpoints vs. the historical, sociological and anthropological left us without a guiding lighthouse.

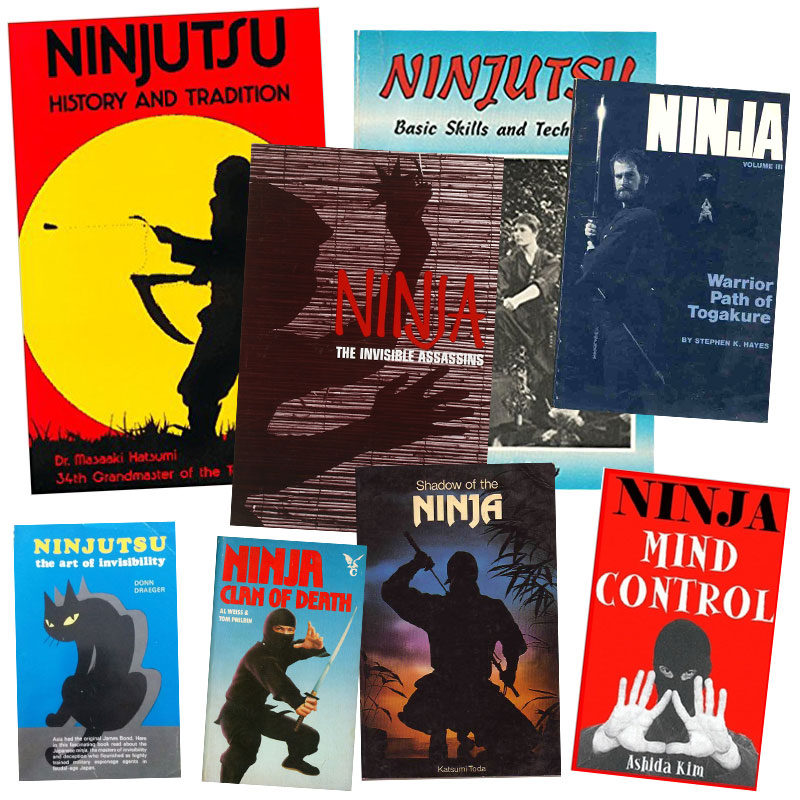

So when in the early 90s (albeit a half-decade too late for the craze fervor) military historian Stephen Turnbull unleashed his Ninja: The True Story of Japan’s Secret Warrior Cult, its stance from a history book point of view, with no ‘dog in the fight’ if you will, was a refreshing voice of reason largely free of the agendas and politicking of the martial arts community (particularly those who had brought the arts to the West). It had copious Japanese sources cited, and no ads in the back for training videos, seminars or mail order weapons. The text would later be honed into two smaller paperbacks aimed at military buffs/gamers and younger readers.

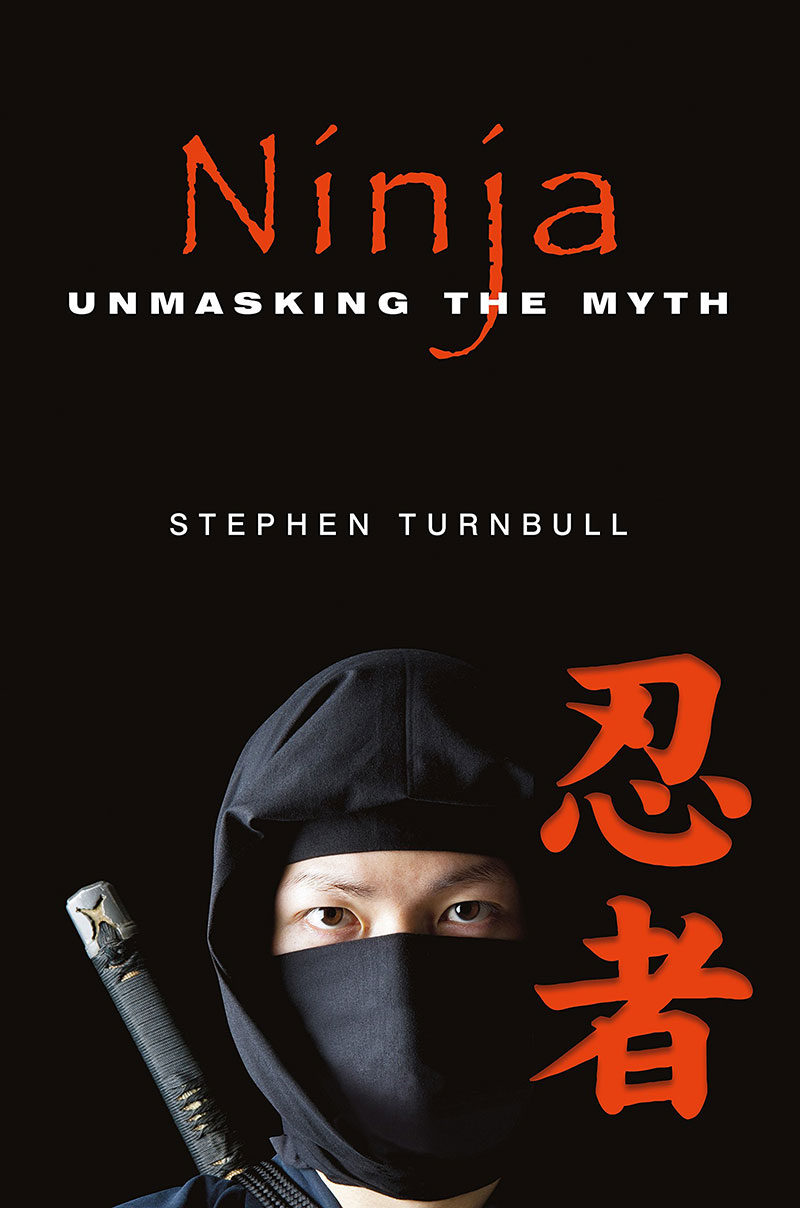

Fast forward to the past five years or so where we see a new surge of ninja history-oriented publishing, largely based on new translations of old Japanese texts, and coming from a more diverse variety of sources than the 80s ever saw — pop culture influencers, well-travelled martial artists whose efforts endured the post-craze decades and new youngbloods parlaying social media and new book-release business models into some high-profile apple-cart-upsetting. Out of this same time, Turnbull’s notions of possibly updating his previous work were met with an abundance of new info and a changing landscape of the ninja phenomenon in Japan, and the decision was made to proceed on an entirely new tome. Finally, this week, we have Ninja: Unmasking the Myth, the new hardcover from British publisher Frontline Books.

This is no mere rehashing of old text tempered by a few new discoveries. Instead it dismantles the entire familiar structure of what we consider ninja, and rebuilds it in what turns out to be a rather pragmatic way that for the first time takes EVERYTHING into account — from the most ancient scrolls to the popular media of the 20th century to the tourism business of tomorrow. Canon is questioned, trusted translations of the past are put through a new ringer, and the timeline of development of what is popularly known as ninja is turned on its head.

But this is NOT a hater rant, not a debunking frenzy, but rather an effort to look at a bigger picture based on the fact that the myths of the ninja are as old as the realities, and the process of creating these historical icons has been evolving and mutating constantly for centuries, and will continue to do so.

Turnbull takes to task repeated efforts over multiple historical eras to create a continuity to the feudal past (typically times of peace redefining what went on in previous times of war) as well as the retro-crediting of old military manuals and written histories (both credible and not-so) as being ninja-releated. He highlights the fragility of translating the very terms “shinobi” and “ninjutsu” and ultimately “ninja” and how liberal usage of those translations had been used to ‘cook the books’ so to say, of history to fit a contemporary narrative. Unmasking the Myth also shines new light on who contributed to the cementing of our current notions of ninja and how recently it was all done.

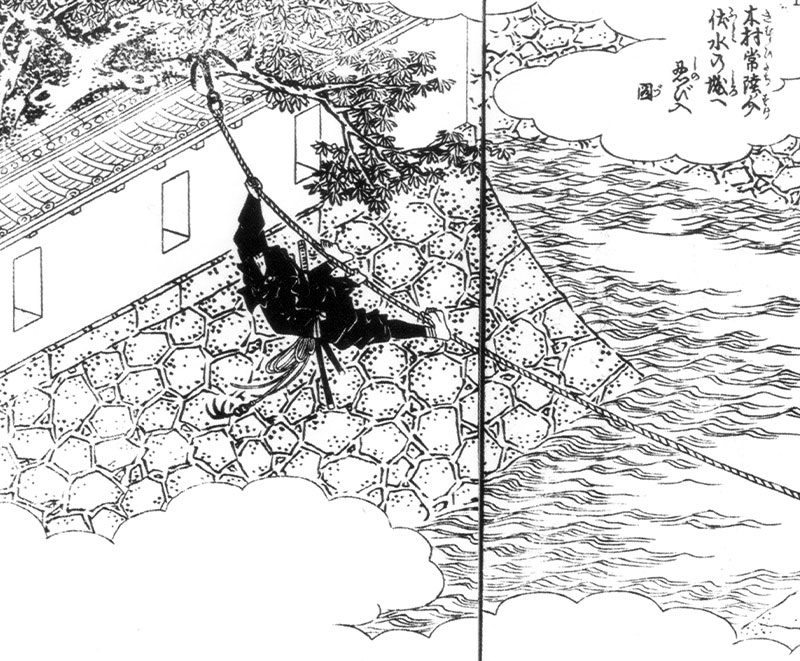

I’m particularly grateful for him including, for the first time in such a book, the genuine role of popular media — from wood-block prints of the late 1800s to early 20th century kids books to the films of the 60s Japanese ninja boom — not as mere footnotes or frosting on the cake, but as vital players in the larger narrative of what has come together to give us the all-too easily accepted definition of the black-hooded set. His treatment of the fabled Fujita Seiko will raise some eyebrows (and probably ires) and he goes on to give the first enlightening exposure to the life and contributions of the man he calls “the inventor of the ninja” Okuse Heishiro, pioneering author and champion of the Iga tourism trade. When it all came together in the 1960s — history texts written for tourists, popularized martial arts, and those same martial artists advising on major mass media projects — we see what he refers to as “a consummate exercise in standard setting” — the release of Shinobi no Mono in cinemas.

IN HIS OWN WORDS

Turnbull’s inclusion of all such aspects of ninja is what makes Unmasking the Myth so PERFECT for the readership of this site. We were fortunate enough to catch the author for an exclusive interview with VN’s particular readership in mind:

VN: Is Unmasking the Myth a replacement for your previous books, or do you see them as a good tandem?

ST: It is definitely a replacement for the 1991 book [Ninja: The True Story of Japan’s Secret Warrior Cult], and in fact most of the illustrations in that book will reappear in my next ninja book, which is the ‘unofficial’ training manual (see below!). The Osprey book [Ninja AD 1460–1650 (Warrior series, 2003)] incorporated some revisions to the 1991 text and of course the color plates are very good.

VN: Are you prepared for the seemingly inevitable controversy that this new academic and wide-encompassing work could generate with the martial arts-practicing audiences?

ST: My experience of martial artists is that on the whole they are a serious bunch who value the ideas and origins of their craft. My book is about ninja, not ninjutsu, but I feel I have presented correctly where the notion of a martial art called ninjutsu came from. As my book makes clear, until modern times ninjutsu meant either the art of the shinobi i.e. espionage, or something magical, not a martial art in its own right.

VN: What would you say to someone entrenched in a modern ninjutsu pursuit who may feel under attack here?

ST: I would hope that any reputable instructor would encourage their students to ask questions about where everything really came from and just enjoy it! Even well-established martial arts systems like judo have controversial histories. Ninjutsu as a modern martial art is nothing compared to some awful hybrids I have seen which are a pick and mix mess of Chinese, Korean and Japanese martial arts dressed up with no historical or cultural background whatsoever.

VN: We in the West see a Japanese source for information and assume it is trustworthy and coming from a position of superior knowledge. You are contending that’s not necessarily the case. Do you feel duped by shady Japanese historical beliefs and how do we behind the cultural and language barriers deal with this?

ST: Just because the source is Japanese doesn’t rule it out from academic rigour and investigation. It must be subjected to the same evidence-based criteria that is applied to anything. Yes, you need Japanese language skills for that, which is why I have tried to be scrupulously honest about my conclusions.

VN: Can you comment on how much historical record seems to be corrupted by translation alone, with “nin” itself being debatable, differences in “shinobi” and “ninja”, the crucial differences in words as nouns vs. adverbs/adjectives, etc.

ST: Yes, see the quote from [Iga-Ryu Ninja Museum director Jinichi] Kawakami that a ninja is a fictionalised shinobi, and remember that the word shinobi meaning spy and infiltrator appears in a Japanese-to-Portuguese dictionary dating from 1603. The two meanings of nin as secrecy and endurance are fascinating topics in their own right because they keep coming up as ninja evolve.

VN: We’re curious, is this book being translated into Japanese for release there, or have its tenets already been covered in other homegrown texts?

ST: I’m trying; it would be the ultimate compliment! There is however so much in Japanese, particularly from Mie University in the last few years, that I don’t think a Japanese publisher would want the expense of translating stuff back from English. Note however that I have received the greatest friendly cooperation from Japanese authors. Why? First of all they are nice people who respect my honest efforts, but also because for every one person who reads their books 100 will read mine because it is in English, so it is in their interests for them to make sure I get it right and of course credit them, as I do.

VN: Movies like Shinobi: Heart Under Blade and mega-properties like Naruto did a lot to deconstruct the trope of the black suit and hood, and even replaced ‘ninja stars’ with kunai knives as the iconic signature weapon. Yet a decade or so later Japan reclaimed the stereotypical ninja suit and shuriken with a vengeance. That look is probably never going away, is it?

ST: No its isn’t. Mie [University] seem to draw a firm line between ninja/shinobi/black suit/shuriken etc AND Naruto/orange suit/space ninja… I am sure we will see ninja in black at the Tokyo Olympics [in 2020].

VN: From the “Cool Japan” campaign to the current boom of tourism redefining ninja as ‘hybrid acrobat/theme park stage performer’ — the invented tradition is once again undergoing mutation. Any speculation as to where we go from here?

ST: The ‘ninja as physical and moral exemplar for youth’ is very hot right now, but that is so Japanese it won’t travel. Western audiences would just laugh at the idea.

VN: Doing what you do as a historian, knowing what you know — are there any ninja movies or shows you still outright enjoy?

ST: Shinobi no Kuni – [aka Mumon: Land of Stealth and Mumon: Land of the Ninja, 2017] is great fun. Seventeen Ninja and Castle of Owls are also favourites. Of course I love watching You Only Live Twice just to laugh!

VN: Finally, for the person who just finished your book and wants more, where’s the next step?

ST: OK, the next step, I am afraid, is another book by me! Thames and Hudson do a superb series for young readers called ‘unofficial manuals’. The brief is to be historically accurate and also light-hearted. So far it includes gladiators, vikings, samurai (by me) and pirates (also by me). The author has to assume a persona, so I have written it as if I was a ninjutsu Grand Master in 1798. Because of that I can write with full conviction that ninja really existed. It’s a bit like Mansenshukai with jokes! (and loads of pictures). Chapters include ‘how to climb into a castle’; ‘how to blow things up’. I have really enjoyed doing it; it will appear in May 2019.

BUT DOES HE BELIEVE IN SANTA?

Unmasking the Myth does just that. While the new book’s criticisms and deconstructions steer towards a larger, more positive effort, I have to believe there will be readers who feel some sacred scroll is being blasphemed. I somewhat sardonically want to see the reaction to his entire chapter focused on Fujita Seiko basically inventing the “ninja star” in the 1930s.

But Turnbull is refreshingly realistic in where this book stands and how it’ll impact the world. While he takes particular task to the notion of Iga being the fountain from which all ninja waters flowed, he also realizes the Iga tourism board isn’t going to stop selling pink and red ninja suits in the museum gift shop anytime soon, either.

A complete skeptic can look at Unmasking‘s conclusions as a begrudging admission by an established expert that the entirety of the field is romanticized fiction and nonsense. A complete zealot could see the same as undermining their martial faith and the sworn testimony of their arts’ ancestry. But those in the middle should come away with an understanding of how time fogs truth and how the funneling of elements into a desired narrative can create an entirely artificial “history” based on unrelated facts. And not to be lost in it all — when the tall tales and fish stories are actually as old as the legit history they are embellishing, the endurance of such is a phenom worthy of study itself.

When it comes to a fascination with anything ninja, we can plunge a foot in the waters of alluring black-hooded fantasy, as long as the other foot is planted firmly on shore. Ninja: Unmasking the Myth is therefore essential beach reading.

Turnbull doesn’t shy away from admitting that he himself was not only a victim of previously-sacred but unsound research, but also how he profited from the popular tropes and iconography of the ninja as an author (and will seemingly continue to do so).

This book has suggested several models for the ninja’s origins as ancient Chines spies, lower-class Japanese criminals, independent jizamurai from Iga and Koka, special forces in a daimyo’s regular army, palace guards who specialized in intelligence work, spiritual exemplars, masked assassins or fictional magicians. The reality of the situation is that all are correct because the ninja is an invented tradition and its inventors could and did choose whatever they wanted.

But what an invention it is! The ninja myth is a complex and dynamic entity that is still evolving today.

He also ultimately encourages us all to continue our fascination with the ninja, but to do so with a tempered mentality and an arsenal of new knowledge now available.

…I believe that there is so much that is historically authentic among the ninja’s antecedents that the invention of the ninja tradition lies less in the creation of imaginative elements than in an inspiring blending of genuine ones.

So it’s like still enjoying Christmas once you’re too old to believe in Santa Claus. And who doesn’t love Christmas, especially if there are some mail order ninja stars under the tree…

Keith J. Rainville — May, 2018

AND, there are plenty of copies of the old book available used, too.

The author’s official website has plenty of additional material as well.

Equally notable colleague of Turnbull Johnathan Clements provided an insightful review of the book with some background here.