If you lived through the 1980s ninja craze, an un-welcomed bi-product of all that wicked awesomeness was the negative media attention it often attracted, including critical malcontents from within. How many times did you read or hear some sentiment along these lines:

“Ninjutsu” has caught the attention of the general public, to the point of phenomenon. Movies about ninja (or alleged “ninja”) are mainstream hits, you see ninja in advertising, on billboards in cities, starring in popular comics. But are they authentic, is this the real ninjutsu? Sadly, no. In the face of their exploding popularity, how far these depictions are from reality and how little solid historical fact is being presented to the general public as an alternative to these mis-truths, is indeed an outrage. Out of respect to the past and in service of the future, the public should be enlightened.

Familiar, right? As the movement got bigger, there was no shortage of this train of thought — reader letters in Black Belt magazine, testimonials from disgruntled dojo masters, complaints of violence in movies, and a few too many bloviated prime-time exposés on TV news alarming parents that mail-order ninja weapons were going to kill their kids.

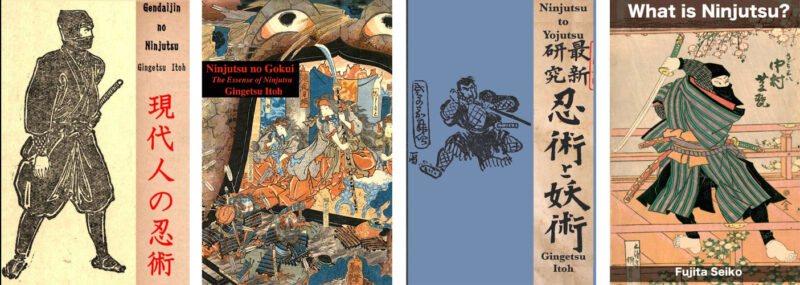

But here’s the thing, the passage above is not from the 1980s. I’ve paraphrased it from a translation of a Japanese newspaper article that eventually expanded into a successful book (seen below). These thoughts were expressed by martial arts and feudal history enthusiast Gingetsu Itoh…

…in 1917.

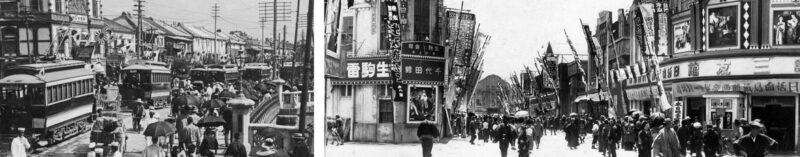

It happened here in the 80s, in Japan in the 60s, but 40+ years earlier, this is not only clear reference to a ‘ninja boom’ in the mid-to-late 1910s, but a craze so prevalent, already out of control even, that it has garnered ninja pop culture’s first outspoken hater! So while the U.S. ended its hunt for Pancho Villa and entered WWI, Buster Keaton made his screen debut while Chaplin starred in three films, and the first ever World Book Encyclopedia was published, Japan was evidently knee deep in ninjutsu!

I have long seen glancing mention of Japanese ninja fads before the 1960s — references to turn of the century literature, martial arts teachings in the 1920s, early animated films, etc. — but a clearly defined picture of what these peaks on the shinobi EKG actually amassed into has been elusive. I always chocked this up to the initial decades of the 20th century being too long and broad a span to define as a singular boom period, nothing as clean cut and defined as the 60s or 80s eruptions. Clearly periods of fascination were there, but metered out only as fast as the times before nationwide print distribution and broadcast media allowed.

However, over the past ten years of so, certain crucial books have been translated, fragments of silent films recovered, and collections of antique tomes digitized and hosted online by American universities. Scanning around all that, even casually, a span of time keeps recurring in various attributions. Admittedly looking back on it through the lens of the 80s craze, and in full realization this may all be leading to a biased false positive, I ask… can we look at the very same year 1917 that the above Itoh book hit shelves, bracketed by a few years on either side, and call it a ‘ninja craze?’ Was this hot trendy ninjutsu thing of the teens as high profile and saturated as the 60s and 80s would be later?

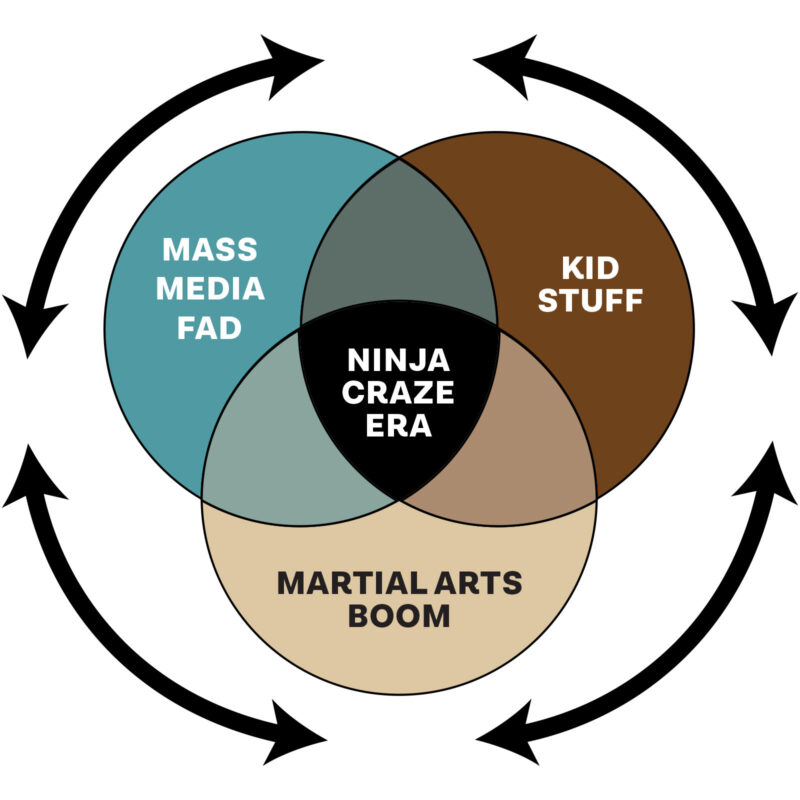

Before diving in, we should first look at what actually constitutes a ‘boom’ or ‘craze’ period like we enjoyed in the 1980s.

Ninja Venn-geance

Looking through that 1980s lens, three things went on, at first independently, but quickly overlapping and congealing into one massive hootenanny. It started with the martial artists — the first folks to even experience the term “ninja” outside of Japan. Pioneers like Donn Draeger and Andrew Adams pollenated their knowledge of the subject to the West in the pages of Black Belt and their own books, but the audience was siloed within the martial arts community. Throughout the 60s and 70 the historical martial arts interest gathered marginal steam, but by the 80s it would be the likes of Stephen K. Hayes bringing a dojo-friendly art back from Japan, teaching it and writing about it, that would truly catalyze a movement within that realm.

That swelling was enough to put the idiom on the radar of a select few media creators looking for new fodder — Eric Van Lustbader‘s bestselling novel The Ninja, and rumor of its major motion picture development, piqued the ears of Golan and Globus at Cannon and they jumped when Mike Stone‘s ninja project crossed their desks, trying to beat the big studios to the punch. You Only Live Twice and The Killer Elite had featured somewhat forgettable ninja in previous decades, with scattered episodes of TV shows like Hawaii 5-O, Kung-Fu, and Baretta planting seeds as well. The 80s began with The Octagon, which felt more like a ninja-infused 70s action flick than something big and new, and Shogun with its influential ninja segments did only air that one time. The real starter pistol, the real flare that went up and stayed up, was Enter the Ninja — an outright declaration of ‘Hey, it’s the 80s and we’re doing ninjas now!’ AND it was on VHS and cable all the time after its successful theatrical run, so we were watching it for years. Things exploded from there, with Revenge of the Ninja and ilk cycling through theaters, VHS and cable TV — perpetually creating new fans and swelling the ranks of the faithful.

As a youngster at the time, ninja were there for me on the magazine rack of the local pharmacy and the spinner rack of trashy beach-reading novels in the supermarket. They were in cinemas, at the video store and on cable. In the karate classes I was enrolled in all we could talk about were ninja and related media. Eagle Force’s Savitar and GI Joe’s Storm Shadow inhabited pegs in the action figure aisles and everything from Marvel Comics to Coke commercials fell in line.

But even more gold lay waiting to be mined — in Christmas lists to Santa, the aisles of Toys R’ Us, Saturday morning and after-school cartoons, Spaghetti-O’s and fruit pies… yes, the kids audience. The shift from a wave of R-rated grindhouse exploitation to mainstream kids fare, safe enough for stuffed animals and Under-oos, was inevitable and immediately profitable to an obscene degree.

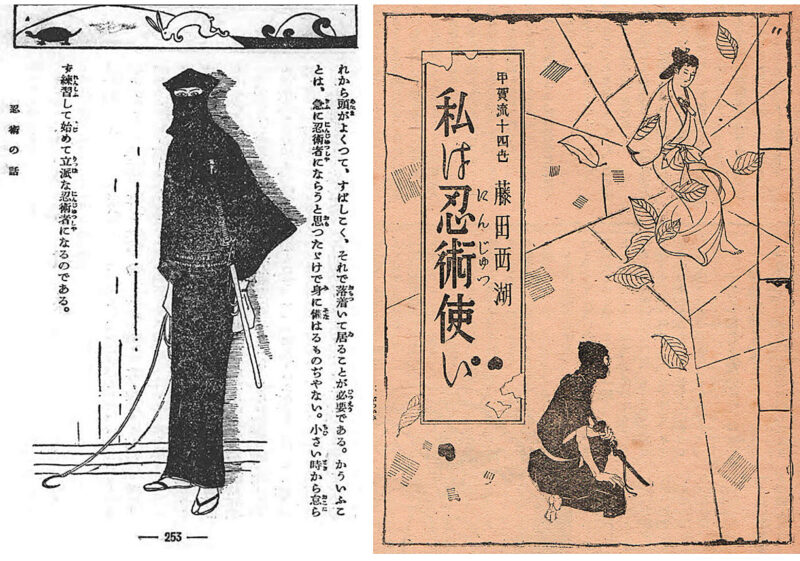

Seen from space, it looked like this:

All of these happening at once, feeding each other (maybe cannibalizing each other) but regardless overlapping, is what made it seem like NINJA was f’n everywhere. In any given decade, one of these things can flourish on its own, and while that seems like big deal within that silo, its not a real boom until it goes wider and interlinks other unrelated audiences, then ultimately the mainstream. In the early 1980s, this interwoven, self-perpetuating overlap turned a once obscure term into a household word you couldn’t avoid even if you tried.

The same thing happened in Japan in the early 1960s. Hybrid shinobi history / martial arts manuals by the likes of Masaaki Hatsumi were big hits, especially the kid’s versions. The Iga tourism campaign was full force pushing the region’s ninja history. Onmitsu Kenshi (aka The Samurai to Australians) was a smash on TV, Shinobi no Mono set the all-time bar for realistic ninja cinema and there was a near-glut of legendary manga from the likes of Shirato Sanpei. It all overlapped, the layers feeding each other, and a ‘ninjas are everywhere’ situation was inescapable.

But what about the time around 1917? You can take all sorts of scattered breadcrumbs — actual hard data like copyright dates, release years, performance calendars, newspaper ads, theater reviews etc. — and assemble them into a rather tasty little snack.

Ninjutsu on Stage

So it’s 1917… and you have tickets to the theater.

The real history of ninjutsu and the historical figures the 20th century saw amalgamated into “ninja” is savagely debated and will likely always be shadows in fog. Regardless on which side of the fence you fall on these arguments, something far more subjective, even quantifiable, is the history of ninja and ninja-like adjacent characters in popular entertainment.

We’ve got centuries of playbills, ticket stubs and financial ledgers of theaters demonstrating how successful stage productions centered on ninjutsu practitioners and related black magicians were, and how far back in time they go. All the various forms of Japanese stage entertainment were rife with familiar names we ninja-maniacs now know from movies and manga.

Starting with the simplest form of theater first — kamishibai — portable busking stalls with over-the-top narrators flipping illustrated screens like comic book panels. This is truly where the modern superhero was born, and ninjutsu was Japan’s home-grown planet Krypton or radioactive spider. Every public park in the country saw kids enjoying magical-powered heroes and black masked villains, with imagination the only limit to their exploits.

Bunraku puppet theater also innovated several things that jumped to the ninja media realm as well. Going back to the 17th century, action-driven samurai tales could take on a whole different level of spectacle when unbound by human limits and physics in general. Dueling puppets flying around the small stage certainly seeded the minds of pioneering anime creators.

The upper-crust of Japanese theater, Noh drama, was rife with supernatural tales and black magic masters aplenty, all portrayed in garish, expressive masks. The hannya demon mask, horned or otherwise, common to ninja movies in Japan and the U.S., comes directly from the Noh stage. But it was Noh’s louder, more obnoxious cousin that provided the first big crossover ninja property in popular entertainment.

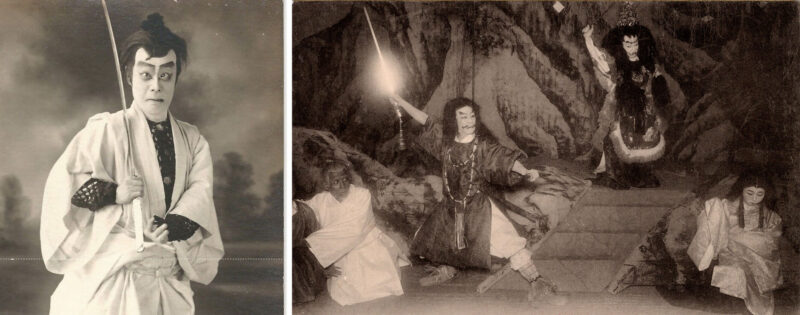

Loaded with over-the-top stylized violence, innovative special effects, face painted heroes and monstrous villains, kabuki theater was the equivalent of summer blockbuster action movies, and the perfect vehicle for tales of black magicians. At center stage, those proto-ninjutsu masters would establish themselves and their arts via the “mie” — a formal trait-defining pose struck and held by an actor in order to introduce his character. Manga, anime, video games, pro wrestling, anything… when you see a warrior hit the scene, bark out his name, and strike a signature pose that is literally trademarked for action figures and t-shirts, that all comes from kabuki.

Kabuki was the perfect damp, warm environment in which the ninja fungus could fester, and the closer you get to the 20th century, the more recognizably ninja-like things got. Familiar names from kabuki fueled the ninja genre in every form of entertainment that followed, including Goemon and Jiraiya.

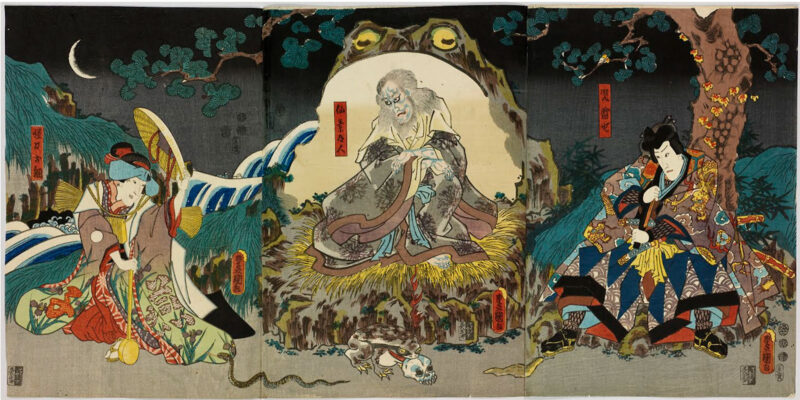

Culled from Chinese folklore, The Heroic Tales of Jiraiya (Jiraiya Gôketsu Monogatari) was a series of over 40 popular illustrated books (you wouldn’t be wrong describing them as ‘pulps’) published in the mid-1840s. They possibly would have remained an obscure footnote in history if not for two things — the illustrations of the legendary Utagawa Kunisada, and starting in 1852, the successful adaptation of the books’ black magic exploits into spectacular special effects sequences on kabuki stages. This is where ‘toad magic’ was brought to life in spectacular fashion, and the ninja genre (and kaiju cinema for that matter) have Jiraiya to thank.

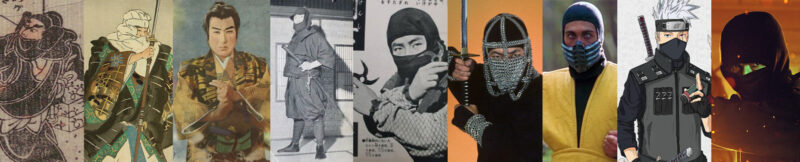

Ishikawa Goemon is a name as rife in lore and pop media as Robin Hood. A famed bandit from the late 1500s and would-be Shogun assassin, his exploits were sensationalized in pulp, stage and silver screen format from the earliest days of those respective media. The more he became an overblown character rather than genuine historical figure, the more shinobi-fied his portrayals became — Goemon perhaps more than any other entity embodies the evolution of fictional ninja, from black magician to black hood.

In our chosen year of 1917 everything old was new again, and depictions of Jiraiya and Goemon were refreshed with Vitamin N. Any strata of theater, from the street busker narrating manga-like panel art to the high-falootin’ stage craft for rich folk, was benefiting from new audiences hungry for ninjutsu magic, and it wouldn’t stop at just the stage.

Ninjutsu in pulp and film

So it’s 1917… you’re a young student in Osaka.

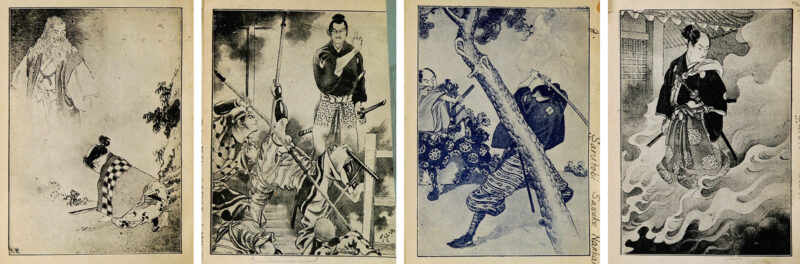

Nestled in your jacket is a Tatsukawa Bunko — a pocket sized chapbook that ALL the kids have become obsessed with in the past two years. The format is trend-driven short prose stories — either stand-alone or multiple issue arcs — with alluring illustrations every few pages. Several publishers adopt it and fight for market share. But it’s the new hot thing that has everyone captivated — jidai shosetsu, historical adventures that have brought samurai history and lore into the pulp era. You’re especially jazzed, because the particular issue in your pocket features the continuing adventures of THE hottest character in Japanese fiction — Sarutobi Sasuke. The ninjutsu-wielding ‘leaping monkey’ is the plucky, defiant hero of a generation of readers. His stories are full of everything a young male could want from a fantasy — princesses saved, skeptical adults won over by a youngster’s heroic deeds, giant creatures summoned, and forces of nature mastered at will.

And this magical super monkey’s latest leap is to the burgeoning silver screen!

‘Brave Jiraiya’ was again the pioneer. The swashbuckling swordsman, and dabbler in ninjutsu magic, had migrated from page-to-stage-to-screen as early as 1912, with two more adaptations coming from rival studios in 1914. Jiraiya was the key in the lock, but Sasuke was the turning of that key and the door was now open to proto-ninja heroes running wild in multiple media forums. Tenkatsu Studios’ silent film production of Sarutobi Sasuke is released in 1915, a time when new fangled cinemas were a sensation in cities and an increasing number of projectors and screens were migrating across the country. Prints would still be circulating and routing into 1917, and by now the film is a massive hit. Enough of a hit to seemingly retro-influence Jiraiya, whose subsequent adaptations leaned more heavily on the ninjutsu aspects of the character. Over three dozen ninjutsu-centric silent films would follow in the next decade.

Both Jiraiya and Sasuke were of the colorful variety, ornate even (especially on stage), with villains like the insidious Orochimaru trending more to darker colors. The outright black-suited ninja commando wasn’t here yet (on stage and screen at least, see below), but the vocabulary for what was to come was absolutely set-up for future generations. By the mid-to-latter 1950s, these same characters would be re-outfitted in black and grey ninja gear and sneaking around rooftops.

Read about Japanese silent film here.

Ninjutsu in the news, and the dojos

So its 1917... and you’re into martial arts.

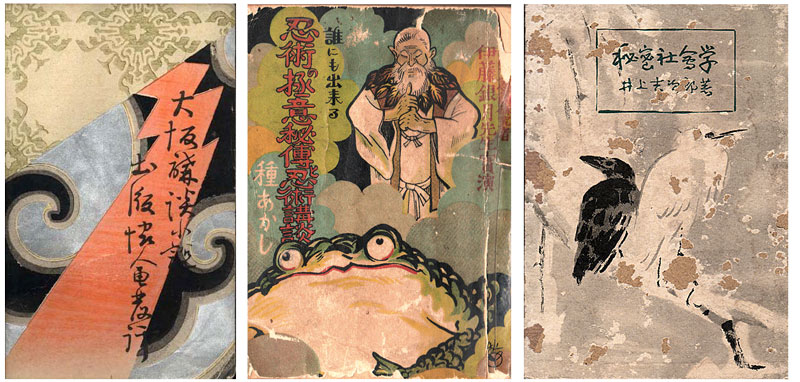

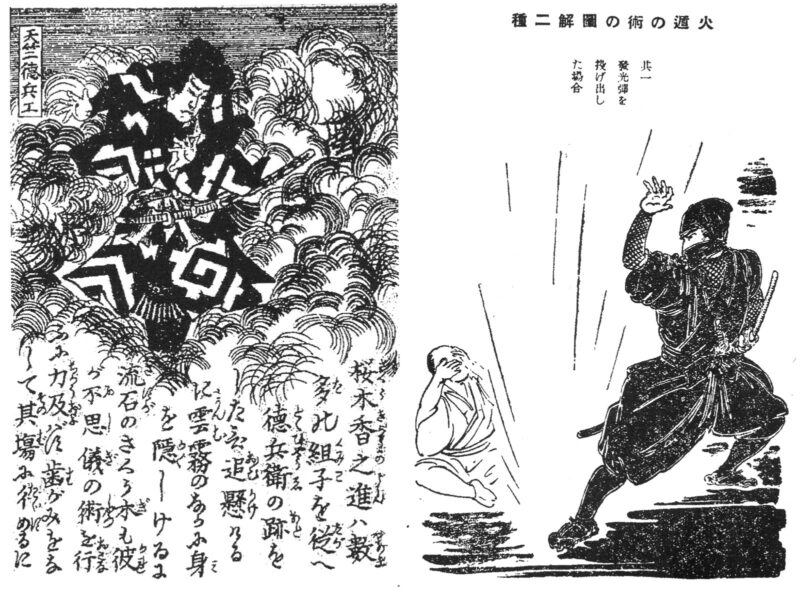

What Andrew Adams did for us 1980’s ninja boom kids in the pages of Black Belt and his pioneering book Ninja: The Invisible Assassins, Gingetsu Itoh (1871-1944) must have been doing for similar audiences in early 20th century Japan. His ninjutsu and martial history newspaper features would prosper into collected book form, starting in 1909 with Ninjutsu to Yojutsu. This first tome boasted revelatory new research on the subject of ninjutsu and its practitioners — the “ninjutsu-sha“ — and linked the shadowy arts of the feudal past to contemporary dojo training and streetwise savvy for the modernizing world. It also wandered into some mysticism, aestheticism and even uses for hypnosis.

By the time his second book, Ninjutsu no Gokui (The Essential Points of Ninjutsu) arrived in 1917, his introductory text became reactionary, defensive and even alarmist in tone, confronting the very real impact that the new technology of moving pictures was already having on the public perception of ninjutsu. Prints of at least six to eight ninjutsu-centric silent films from three different competing studios were all touring the country as this second book hit shelves, so it is no surprise that the initial chapter was dedicated entirely to correcting newly amplified misunderstandings about ninjutsu. It would seem the race between academic history and silver screen sensationalism was over before it begun, and to this day credible reality has placed a very distant second.

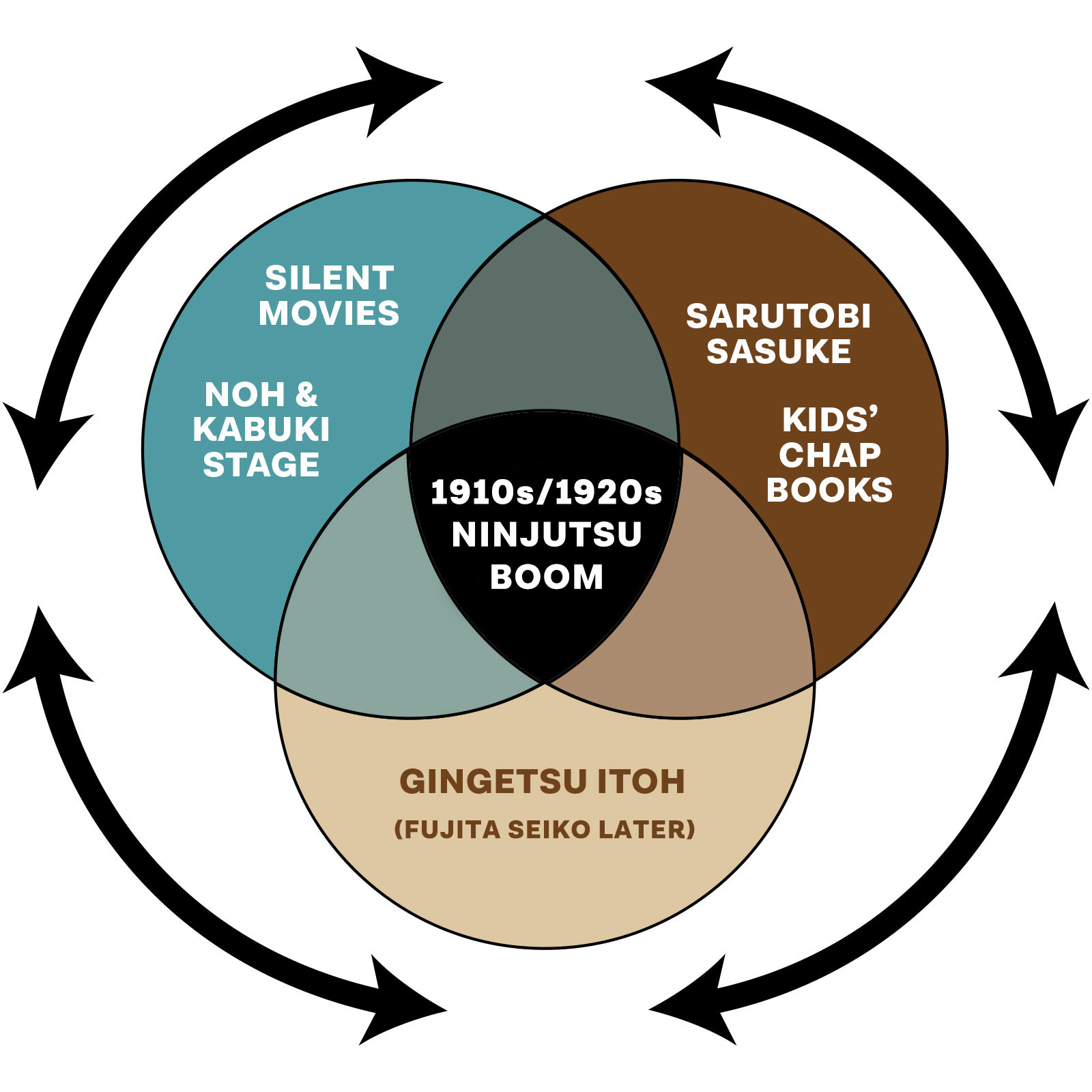

What’s kind of funny here is Itoh started to incorporate images of black-clad ninjutsu practitioners into his texts, which in his eyes would have been the more credible down-to-earth alternative to the ornately colorful Jiraiyas, Goemons and Sasuke’s on stage and screen. This look wasn’t cool enough yet to escape the boundaries of martial history interest though, it would take the post-WWII Bond era and gorgeous greyscale Fujifilm to catalyze that. Then in the 80s the snake ate its own tail with the skeptics and haters calling the ‘ninja suit’ a ‘Hollywood’ myth.

A few caveats…

It’s worth side-barring here and wandering a bit past 1917.

Itoh shifted tone in a 1937 book Gedaijin no Ninjutsu (A Modern Practical Guide to Ninjutsu). It also began with a chapter reinforcing the real vs. the wildly fictional, but then it quickly gets down to business portraying a codified practice and study of the modern “Nin-sha” as structured and organized as any other formal dojo-bound martial art. The final chapter calls for the incorporation of the ninjutsu mindset into modern military training as the world sat on the brink of war. This book was positively littered with illustrations of trademark black-clad, hooded, mesh-sleeved nin-sha performing all sorts of tricky subterfuge on samurai swordsmen — an outright blueprint for the ninja books that became huge in the 60s and 80s. So twenty years after his 1917 rant about sensationalizing ninjutsu, here he was chiseling in stone what some consider an equally fictitious iconic look.

By then Itoh would certainly be either influenced by, or reacting to, the legendary Fujita Seiko (1898-1966) — the century’s first shinobi celebrity, a man who was to ninja what Houdini was to escape artists or Evel Knievel to daredevils. Starting in the early 1920’s, Seiko would also write history articles for newspapers and journals, publish books on ninjutsu drawn from his treasured collection of centuries-old scrolls, and become that go-to expert whenever an author or journalist was working on something ninja-related. Seiko’s schizophrenic career would see him give public exhibitions of credible self defense techniques, teach at the military’s Nakano Spy School and become the voice championing the adoption of ancient shadow techniques for modern warfare. He’d also claim to have super leaping powers, communicate with ghosts and sold tickets to carny-like human pincushion performances. Posterity has never known quite what to do with this genuine enigma of a figure. He embodies a yin/yang of historical significance and sideshow aggrandizement that rather parallels the serious-vs-sensationalistic nature of the entire ninja idiom itself.

Our hypothetical ninjutsu fan with his nose buried in a Sasuke pulp in 1917 would be in his 30s when the black-suited ‘ninja’ started to replace black magic wizards with more down-to-earth commando/spy exploits. One wonders what he thought of it all…

Re-VENN-ge of the NINJA

OK, so now let’s refocus on that 1917. You can see a ninjutsu practitioner on a kabuki stage or a silent movie theater, read a Sasuke romp on the train the next day, and browse yet another shinobi editorial from Itoh in the daily newspaper that night. And just a few years later there’s even more movies, wider distribution of popular fiction and proto-manga, and the movement’s celeb figurehead Fujita Seiko making a spectacle of himself. This sounds a lot like the wave we were surfing in the 1980s.

Were the years leading up to this, and immediately after, an explosion of activity like Japan saw in the 60s and the rest of us in the 80s?

Not quite.

Keep in mind in the eras before modern broadcast media, these things spread slower and more organically, and went into remission slower too. We’re really looking at a few decades of interest on either side of this. Plus film was so new, you can chart a bigger boom of ninjutsu-centric movies a decade later, simply because there were more and more theaters and studios active as the industry grew.

And… it’s really important to realize the black suited commando illustrated in an Itoh or Seiko book is far from the same character archetype as the swashbuckling mountain magician punk kid of the pulps, stage and screen. A young teen might have both a Sasuke pulp and an Itoh martial arts history book on the same shelf, without even fully connecting the two. These disparate idioms would eventually converge post-war, but it wasn’t until the 60s that they really blended into what we love today.

Author/translator Eric Shahan has posted on social media quite a bit on the differences between a ‘ninja boom’ the way we see such and a ‘ninjutsu craze’, and I can see that argument. It’s more than mere semantics.

But damn… this 1917 year sure as hell does look like a dress-rehearsal for what we experienced in the 80s, and I just can’t let that go. I’ve always credited, and I’m not alone in this, the very clearly defined 1960s Japanese ninja craze as being the first time the idiom truly swelled to household awareness. Thus, the decades before, while littered with plenty of blips on the ninjutsu radar, were more of a long slow groundswell that allowed the 60s eruption to finally take place. But maybe that 60s boom was actually a reboot of previous movements, adrenalized by slick new color magazines, million-print-run national manga and programming on the movie, and now TV, screens?

While there are all sorts of archeological relics of proto-ninja fixations from previous eras, in the years around 1917 Japan would be witnessing the first time martial arts, military history, an iconic kid’s hero in best-selling print media, myriad forms of theater old and new, and perhaps most importantly the exploding new-fangled motion picture, were all available at once. And all of those realms found new heightened success with ninjutsu content, and likely nourished each other to a degree.

Also note this ‘boom’ didn’t fizzle after a decade the way the 60s and 80s ones did. The Venn diagram has even more overlapping material in the late 20s and 30s as well — more publishers, more studios, more audience and what have you — I suppose the question is was this one long period of steady popularity, or subsequent fads with down periods in between?

That dude from 1917… is ME

I was a young teenager when the 80s ninja craze caught fire, and I was into the martial arts stuff, the comics, the movies especially, was buying action figures well after the age I was willing to admit to doing so, and Stephen Hayes and Sho Kosugi were my gurus. Three decades later, after high school, college, jobs, multiple moves and life in general got in the way, I rekindled that same fervor. I delighted in finding the old stash of magazines and mail order weapons surviving in mom’s basement, I connected with others online of similar ilk, and I sat watching Castle of Owls and Mission Iron Castle for the first time, as gleeful as I was back when Revenge of the Ninja hit HBO.

Knowing how my teenage, and then mid-life, mind and heart took to all things ninja, I can image our hypothetical youngster in 1917 Japan the same way. He had his comics, books, movies, martial arts fascinations, etc. and so forth. Then next couple of decades would be pretty rough on him, but if he survived the tumult of mid-20th century Japanese history, I like to think he came out on the other side of it still loving those “nin-sha” of his youth. And I bet his grey-haired and bespectacled self would have been in a theater on opening weekend of Shinobi no Mono, as wide-eyed as he was as a kid, watching it all be reborn for a new age.

Keith J. Rainville — March, 2025

AUTHOR’S POST-SCRIPT:

I am hardly THE authority on anything above (in fact I’m rather nervous one of the legit experts cited here will shred it all to a point of humiliation), but I was driven to assemble this feature out of frustration that such analysis really hasn’t been out there in one place. With the continued corruption of social media and exodus of its better voices, online platforms disappearing entirely, and the not-so-slow death of the internet as we knew and loved it, I’m more concerned than ever that material like this be given a more stable home. To that end, I really want your additions, concerns, corrections, etc. and look forward to future updates of this first attempt. It really needs to be better than scattered Facebook posts, deleted Tweets, defunct blog entries, and YouTube vids in danger of copyright strikes. So I’m willing to hear everyone’s take in an effort to cement this into something better and yes, permanent.

NOTES AND THANKS:

Eric Shahan has translated all of the Itoh books and several Fujita Seiko works referred to in this piece and I highly recommend checking them out, amongst the rest of his adjacent work. See it all here.

Read of Fujita Seiko’s life in Phillip T. Hevener’s Fujita Seiko: The Last Koga Ninja and the writings and translations of the man’s works by Don Roley and Eric Shahan as well.

Adam Robert Turner on Facebook is well worth following, and join the group Historical Ninjutsu and Samurai Warfare for more.

Many thanks always to the Tru-Flyte Martial Arts Memorial Website and the collections of Charles and son Robert Gruzanski.

The University of Pennsylvania has an ample collection of period literature mentioned above, read about some of it here.

Princeton University on Sarutobi is also a good read.

BkrBudo links Sasuke to various martial arts traditions here.