There were a hundred or more movies and TV shows delivering a consistent, almost branded, ninja idiom in Japan during their 60s craze. Entering 2026, we have access to more of that astounding vintage media than ever before, and posterity is going to credit film and TV as the dominant forces that drove the mid-century shinobi renaissance.

But realize this… in the mid 1960s a movie had its time in the theater then went away. No VCRs, no cable TV, no on-demand streaming. A TV show aired once, and maybe got re-run months later, but you couldn’t watch and re-watch endlessly like we do now.

The reality was, if obsessed fans wanted a daily ninja fix, if some friends wanted to ponder over weapon designs or mimic poses and techniques in the backyard, if a kid needed a good dose of Sasuke and Hanzo at night to send him off to dreamtime, the only source of fuel was PAPER.

The movies and shows might have shined brighter during their brief time in the spotlight, but it was non-fiction books and magazines, aimed at a variety of age groups, that did the heavy lifting day after day. Well-read, beat-up dog-eared pulp was scrutinized for more hours by more people, and could be brought to school, traded, passed-on or left in the loo for another family member to discover.

These tomes turned lore and tall tales, military history, contemporary martial arts, manga tropes and iconic character designs into formalized cannon, gospel chiseled in stone. They created a knowledge baseline, and common vocabulary, that seeped into the culture. And then they’d serve as research for future decades of movies, comics, toys, video games and more, never mind serving as templates for seminal works fueling the West’s ninja boom 20 years later.

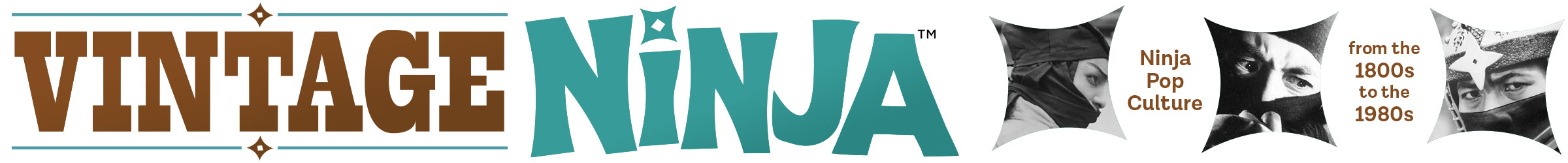

In short, a legion of books made the fervor for ninja more than just fandom, they made it academic. And the black hood and sword across the back was always the lead.

Was everything in these books historically valid? No. They were products of their times, and leaned on the shoulders of way too few researchers whose findings were unquestioned until recently. Plus, the sensationalism of black hooded commandos doing superhuman martial arts was what sold copies and graced their covers, almost categorically.

Some admittedly flawed human psychology is at work here — books seem more authoritative, we assume books have a THEY that is vetting these things, it’s our nature to lazily assume their reliability. In some cases that’s totally legit, publishing (especially in decades previous to our dystopian-in-progress present) had a lot more clout and was a nobler field — and one assumes a book editor to be a more responsible, less mercenary or lascivious sort that your average studio exec or exploitation film director.

Truth is, the books cemented a lot of unsound notions, silly media tropes and tourism myth-building. However they were also sometimes surprisingly candid in their admission the exploits of legendary ninja were little more than fantasy dressed for night work. Ninjutsu icon Masaaki Hatsumi wasn’t shy about the fact that, especially with the kid’s books, he was giving the public what it wanted, while any sort of real lethal martial traditions remained sequestered in the shadows.

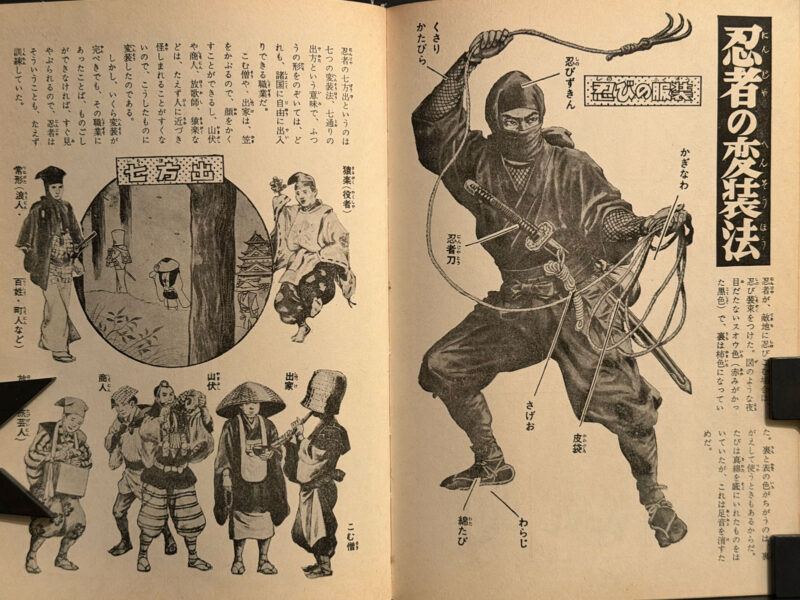

There’s some common framework for these non-fiction ninja books, following is a quick rundown.

Multi-Styled and Multi-Purposed

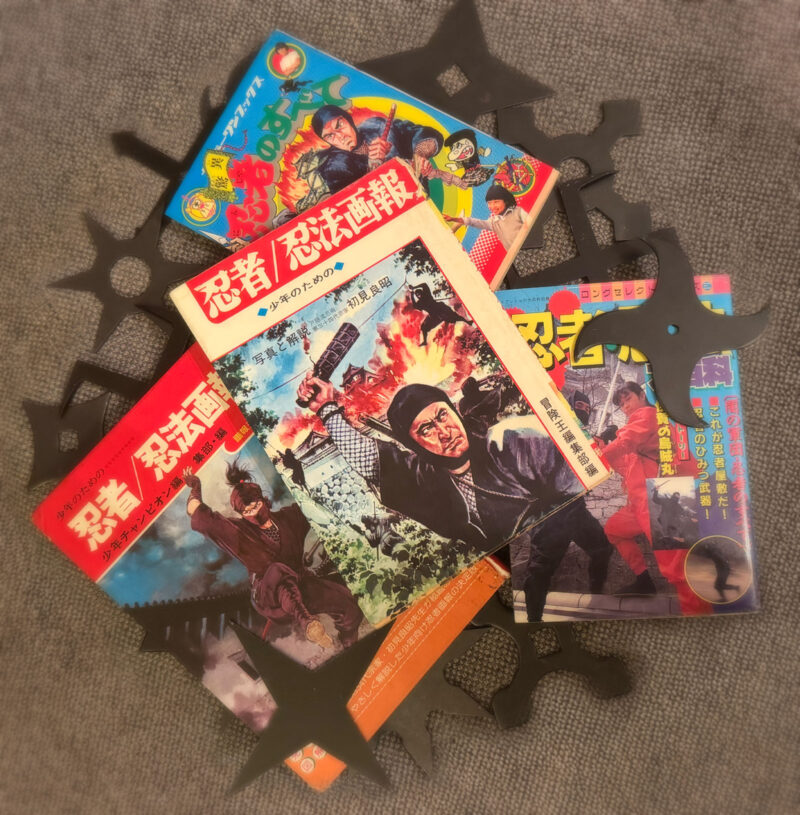

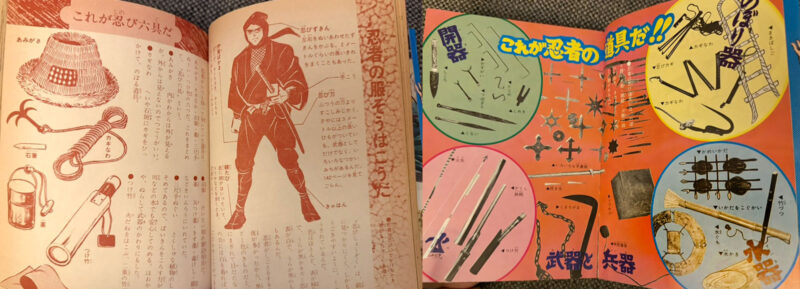

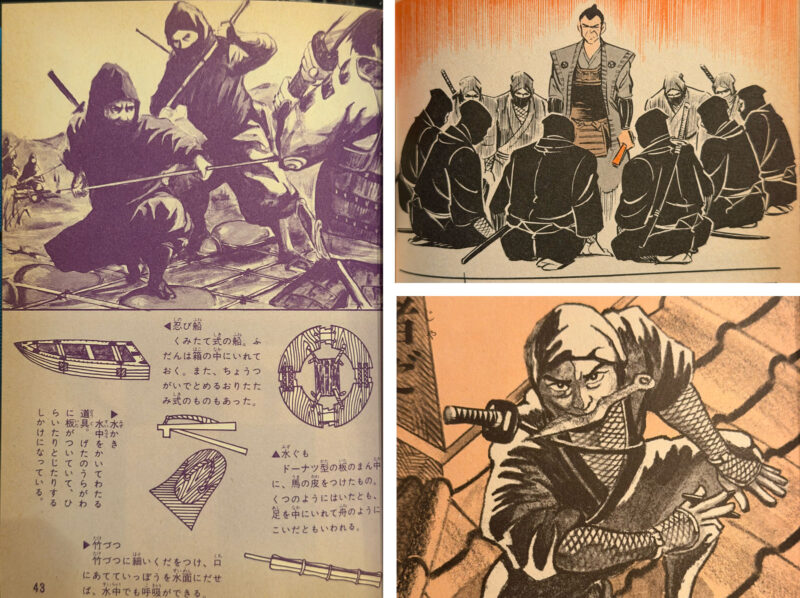

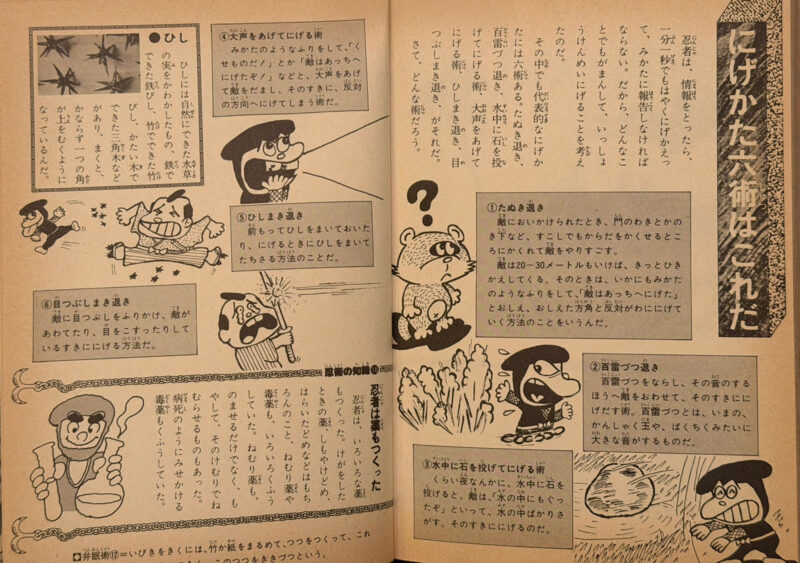

If all you’ve seen from ninjutsu books are grids of photos of dudes in black gi’s tumbling on mats, you’ll be struck right away by how crazy busy and multi-styled the Japanese equivalents are from chapter to chapter, section to section, with entirely different media living hand-in-hand. These were like a Las Vegas buffet of black hooded mayhem. An initial spread of color photos of historical gear and weapons would be followed by 20 pages of manga story with Hattori Hanzo saving the Shogun, then a chapter with press photos from contemporary ninja films, then cartoon strips of comedic ninja characters demonstrating techniques of espionage, back to more photos of landmarks and battlefields and castles, followed by mechanical illustrations of sword canes and explosives and the like. It was like Ninjutsu-ADHD, sugared up on Botan Rice Candy and Calpis.

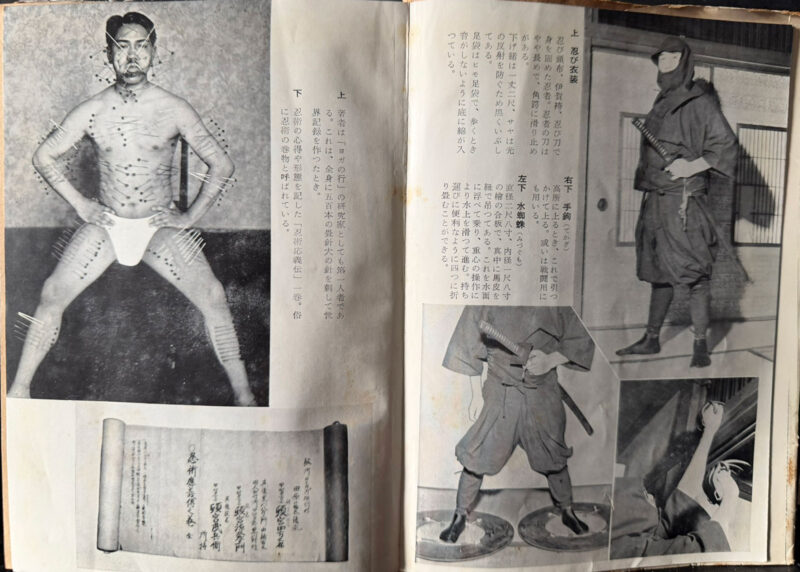

Take the above, from Masaaki Hatsumi’s Ninjutsu for Boys — a single spread containing martial arts demos from a dojo, illustrations and photos of historical props, a press still from the Shinobi no Mono film series and a portrayal of manga hero Kagemaru of Iga. This multi-disciplinary collage blitz would continue throughout the book.

Repetitious and Inbred

Another thing you notice right away when looking at these books is how repetitive they are in content. Illustrations and photos were recycled between magazine articles and book chapters, and expanded new editions were often just combinations of repeated elements from other previous titles. And all of it was telling the same story over and over again…

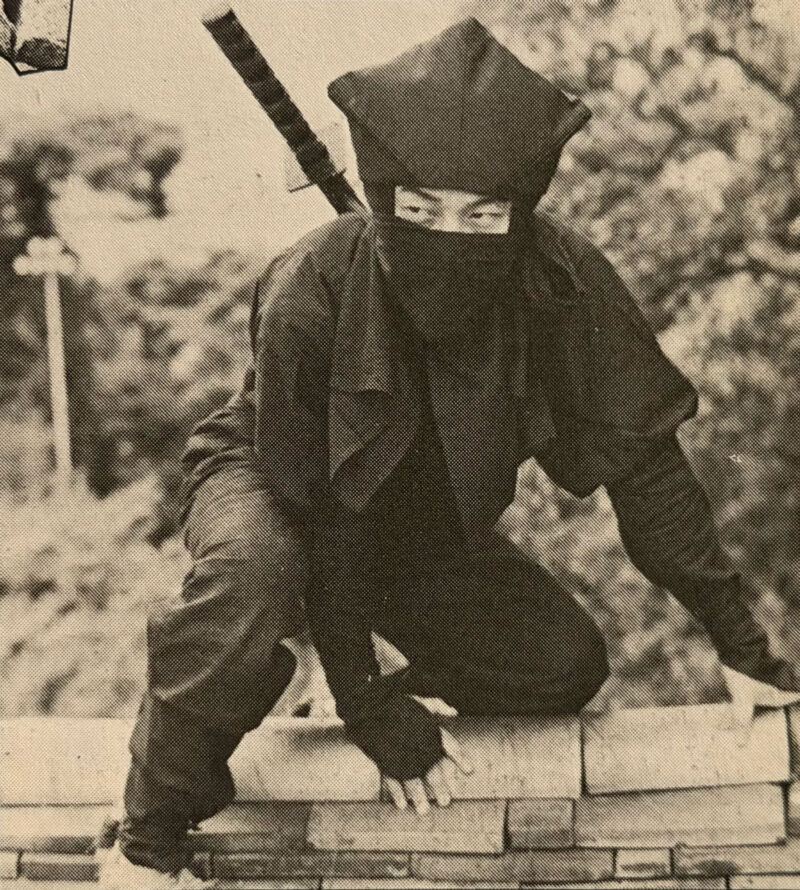

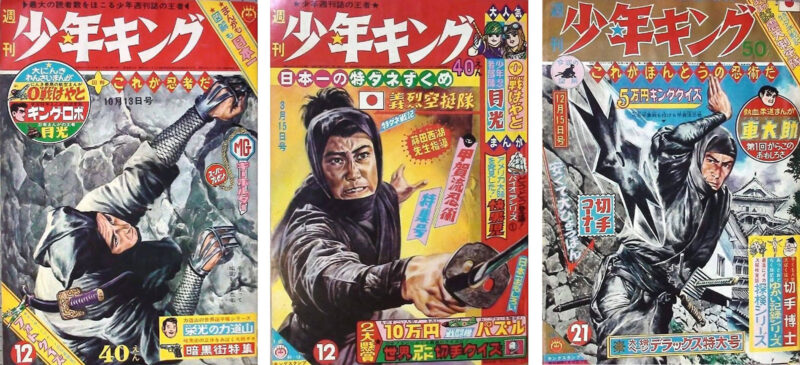

Above is a sampling of “Shonen Champion” magazines of the 60s, where much of the art for the books below either ran first or was recycled from. The ninja-crazed public was endlessly willing to double dip at any given time. Think of it like Black Belt Magazine here, publishing ninja articles from Andrew Adams over the years, which were then collected and reorganized into the best-selling book Ninja: The Invisible Assassins. Decades later you’re way more likely to find a beater old copy of that book that you are any of those individual issues, so it’s when the material jumps to square-bound book format that it reality enters the posterity pool.

And here’s probably the best example of that posterity pool cannibalizing itself… Masaaki Hatsumi’s What is Ninjutsu featured the illustration at right, which has been copied, bitten, ripped-off, whatever you want to call it, ever since it was first published. Check out the manga-styled adaptation in the below competing Japanese book The Ninja Encyclopedia. It’s also been outright plagiarized in a few books from England and the States in decades since.

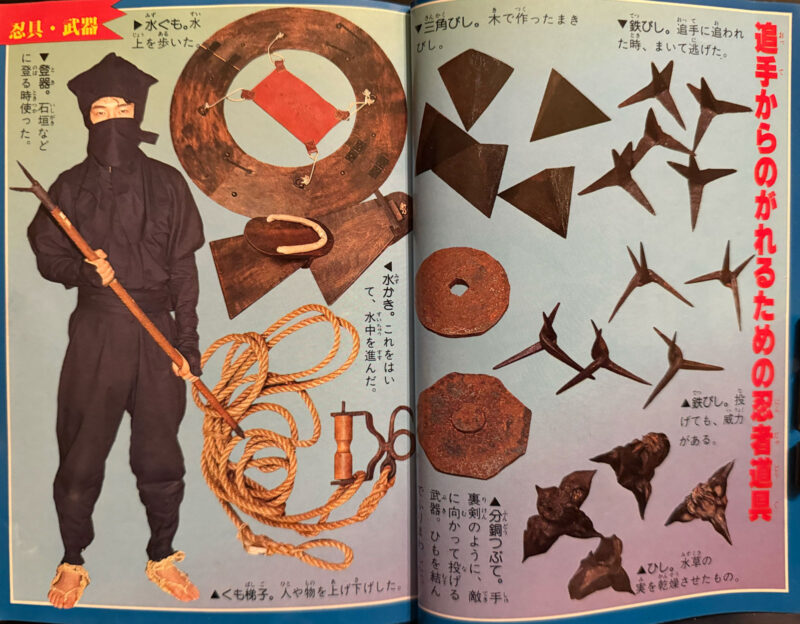

Even when a book was supposedly all-new or from a competing publisher, it covered most of the same ground — you see all the usual suspects repeated: shuriken photo collages, re-enactors from the tourist villages modeling ninja suits and demonstrating trap doors, water-spider wooden shoes and bamboo-punk gadgetry diagramed as if they were science. Most all of it is funneled conclusions from the work of three men — Gingetsu Itoh starting in the 1910s-20s, Fujita Seiko in the 30s and 40s, and Heichiro Okuse acting as tourism magnate for the Iga region starting in the 1950s.

Credible and Sensational in Equal Amounts

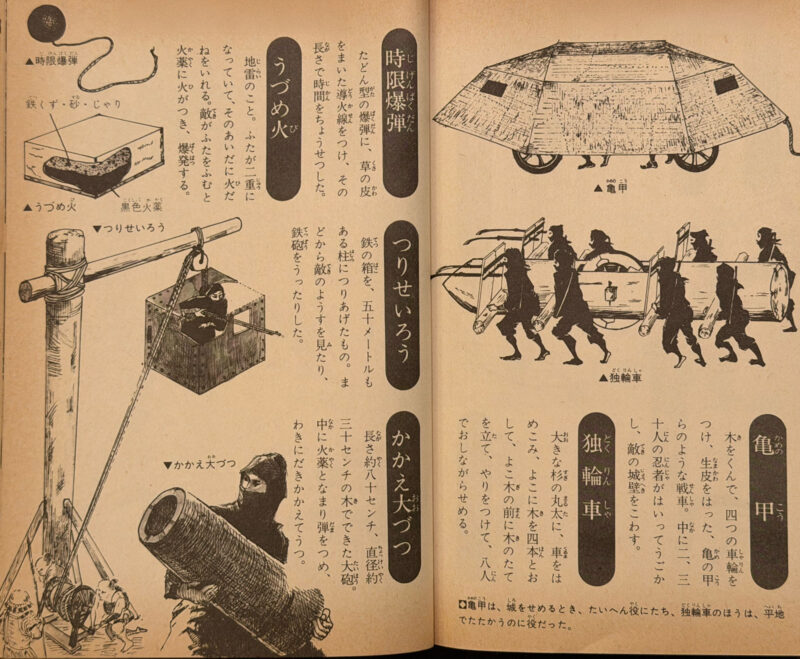

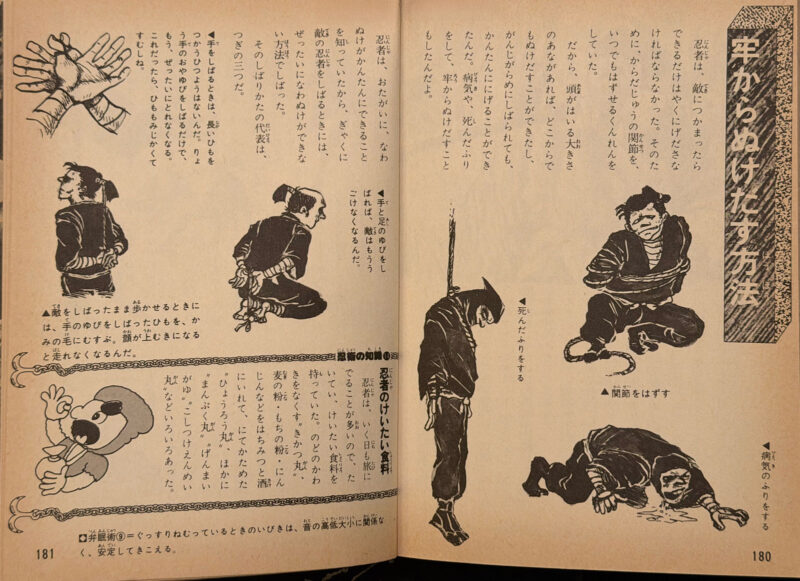

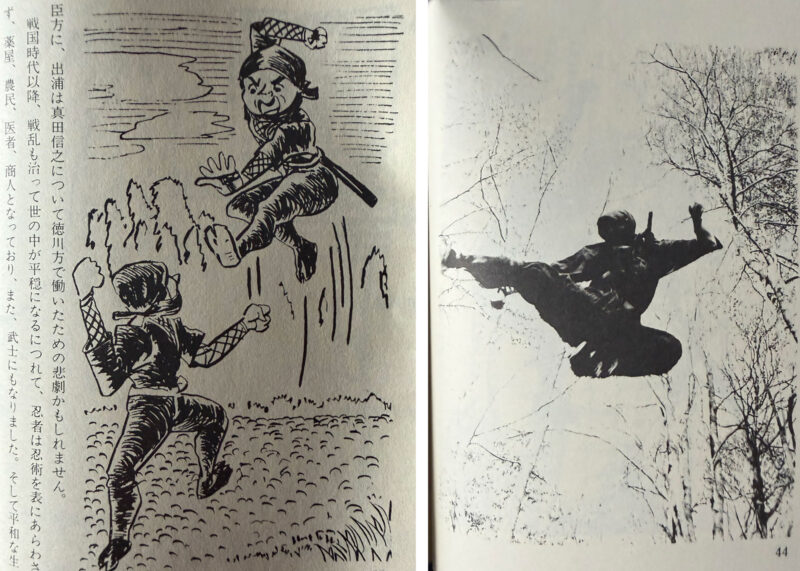

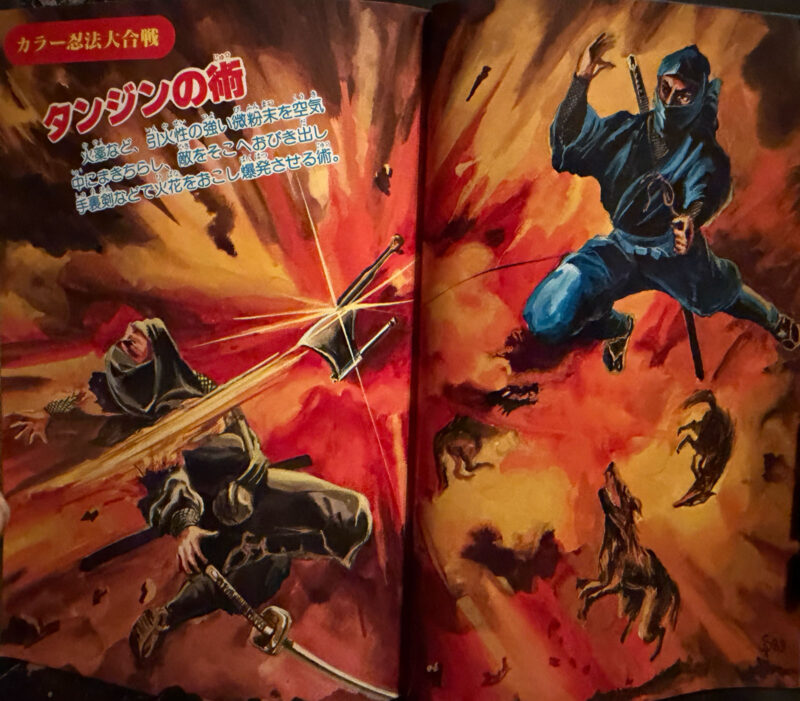

Consistent in most of the books I’ve seen, especially the kids and teenage boy market books, is the full-on embracing of both ends of the pendulum — credible history and spectacular tall tales. One book will have spreads on real things like nightingale floors or pilgrim-monk and traveling musician disguises, then 50 pages later we get illustrations of bamboo submarines sculpted like dragons, bombardiers flying over castles on kites and water wheels that catapulted ninja squads from rivers over fortress walls.

These publishers were not afraid to sell books — they were running full speed with every black hooded trope, kabuki magic act and spectacle-filled fairy tale they could, and nothing so dour as historical credibility was going to slow them down.

Like here, more pages from Masaaki Hatsumi’s What Is Ninjutsu demonstrating legit gadgetry like pyrotechnic shuriken and ‘black egg’ powder bombs, and from the next chapter a submersible dragon-themed nautical craft loaded with ninja sailors (‘coincidentally’ featured in a season of the mega-hit TV show Onmitsu Kenshin).

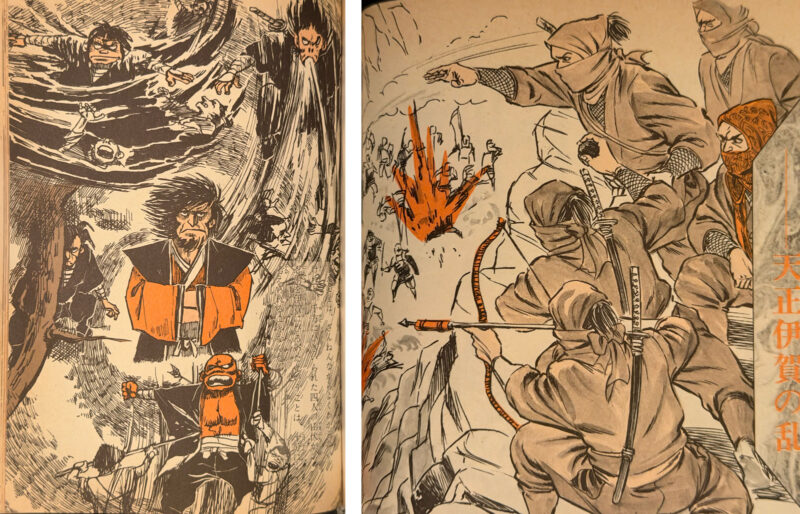

Unsung heroes of Ninjutsu

With the sort of saturated exposure these books lent, the artists within were indeed the real heroes here. They did the same thing for shinobi that Howard Pyle did for our notion of pirates and N.C. Wyeth did for Robin Hood. Look at how many book cover artists or interior illustrators informed the entirety of a property. Conan didn’t look like Conan until Frazetta, and every Conan project since, from the 80s movies to modern comics and video games are just trying to capture the same magic. Sherlock Homes was never described as wearing the trademark houndstooth hat in Arthur Conan Doyle’s texts, it was cover artists who locked that look in well before film and TV.

So with their work more viewed than any film or TV show, and them cementing the look and stoking the demand, you’d assume artist names would be emblazoned all over the tomes they made so sellable?

Alas… Illustrator credits throughout these books were buried, if even present at all. When they were credited, it was just a nondescript group listing lacking specific identification for any given work. So for the mere sake of giving them SOME recognition, here’s a list of artists I was able to glean whose work you’ll see throughout this article: Ikukuzo Ito, Yu Kimono, Sinichi Matsuyama, Yukio Mihara, Takashi Kato, Kaneya Ueki, Hiroki Sato, Shin Takashita, Masanori Yagi, Shigenori Yoshiura, Toshiaki Mori, Toshiaki Shinohara, Masahiro Mihashi, Tadashi Nakazato. The manga creator for the Hatsumi books was Shinichi Sato.

So Let’s Look At A Few…

This Christmas I gifted myself a few more of these vintage books to an already too-expensive collection, so allow me to justify some tax write-offs here, and let’s take a look at the ink and paper realm of the 1960s Japanese ninja boom…

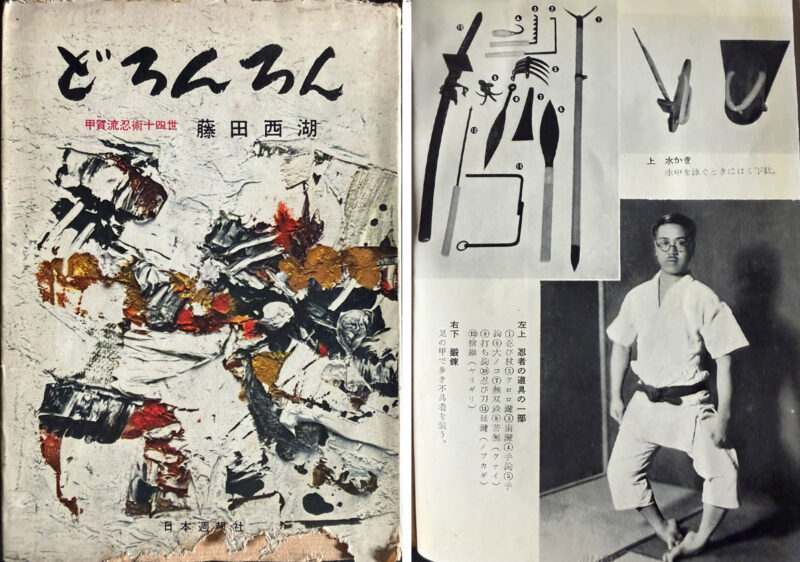

Fujita Seiko’s Doronron: The Last Ninja

Originally published in 1958, this 5.x7.5″ 265-page paperback is an amalgamation of material previously seen in newspaper articles and other books from past decades, released right at the fuse-lighting stage of Japan’s 60s ninja boom. Seiko was outspoken in his concern about mass media aggrandizement of ninja as entertainment, and a swelling demand for shinobi based on the success of some late-50s movies (Sarutobi Sasuke reboots) may have triggered this new collection. Alas, with Shirato Sanpei’s Ninja Bugeicho coming a year later and several more movies in the pipeline, the cat was already racing towards the bag’s opening…

The book is primarily text, with a few glossy pages inserted into the front featuring photos of the recently opened Iga museum exhibits, and classic photos of Seiko’s outré carney-type demos. Such was the schizophrenic nature of ninjutsu’s first celebrity expert. He would pass away eight years later, at the zenith of the ninja craze, but his writings have remained in print to this day and more have been translated into English than ever before.

Masaaki Hatsumi’s What Is Ninjutsu and Ninjutsu for Boys

In the mid-60s the man then known as Yoshiaki Hatsumi was making a career out of curating the disparate knowledge of ninjutsu’s obscured past and reshaping it all into a dojo-based martial art for modern times. He had become THE go-to guy for technical consultation on movies and TV, made the talk show circuit, gave demos for the likes of James Bond creator Ian Fleming, and more… but his farthest reaching impact by sheer numbers were his best-selling books aimed at wide-eyed young readers. Hundreds of thousands of teens and kids were grabbing flashlights and reading these under the covers well past their bed times, indelibly impressed by images like this.

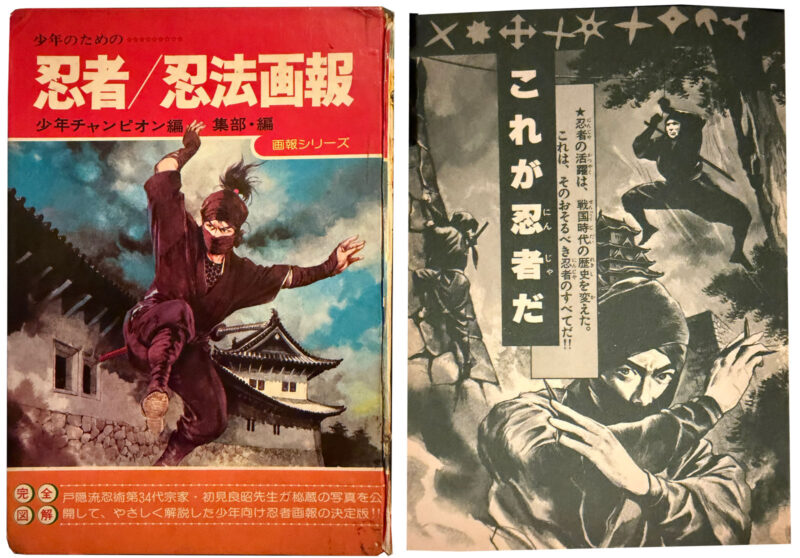

Ninpo Gaho was originally published as a hardcover in 1966, and kept in print through the 70s and 80s (mine is a 1971 paperback edition in a 6×8″ size, 160 pages). Claiming to be “The only book you need to learn about ninjutsu!” it seems to have been the trend-setter for the multi-media approach, dealing with both history and fish-tales in equal amounts, and bolstering the content with popular movie and TV show photos profusely. Hatsumi may have championed ninjutsu as a serious martial art with centuries of tradition and pedigree, but he was in no way denying the popularity of movies, TV and comics as the reason anyone was interested in the first place. In these pages, he was using those media properties as the shiny lure, then hooking readers into more credible matters as best he could.

Above is from an intro section loaded with stills from the massively influential and popular network TV show Onmitsu Kenshin (aka The Samurai to Australians). Stars Koichi Ose and TV’s #1 ninja Maki (Tonbei the Mist) Fuyukichi provided interviews and texts. We also see the hit film Kaze No Bushi (Warrior of the Wind) and collages of iconic shuriken, which dominated the up-front sections of Hatsumi’s and his competitor’s books — audiences wanted to see ninja stars right away.

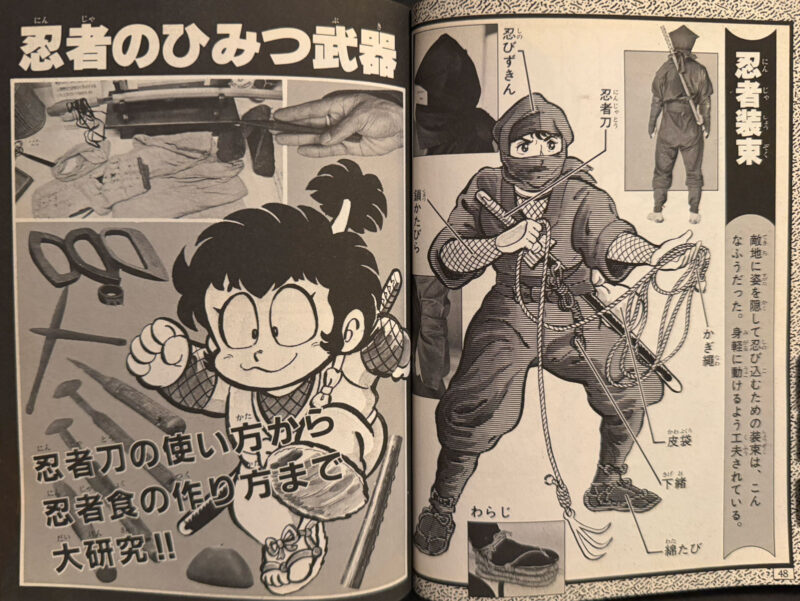

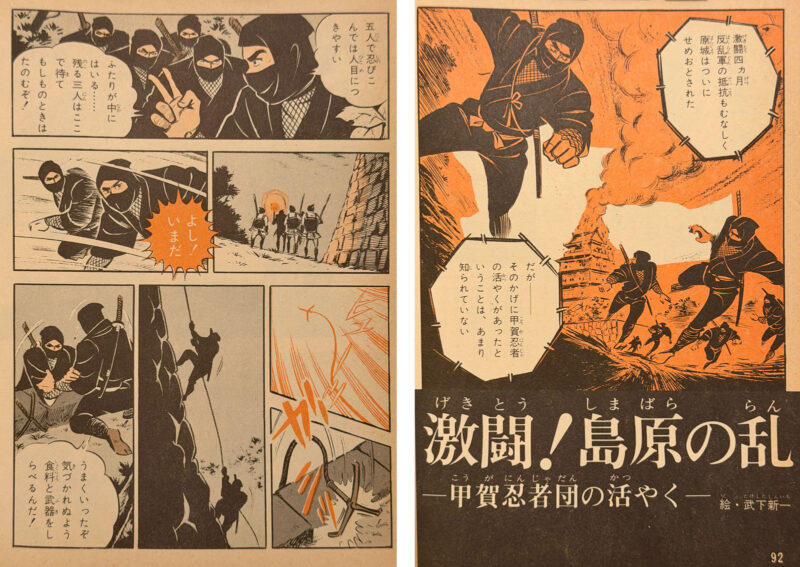

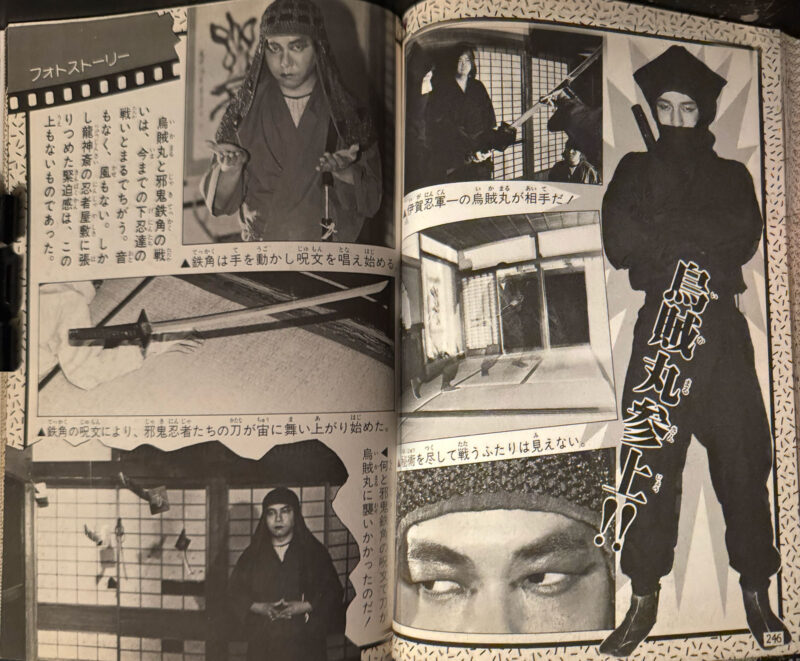

Ninjutsu for Boys (also translated as Ninjutsu Pictorial for Boys or Ninjutsu Illustrated for Boys) recycles much of the same material. This is a 1977 hardcover edition by Shonen Champion, edited by Akita Shoten, and it is just loaded with amazing art.

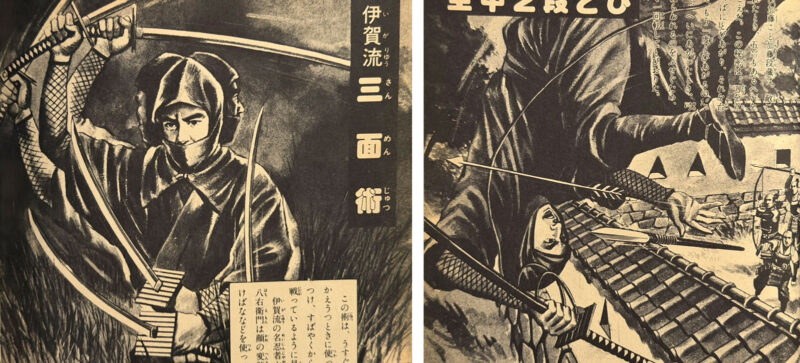

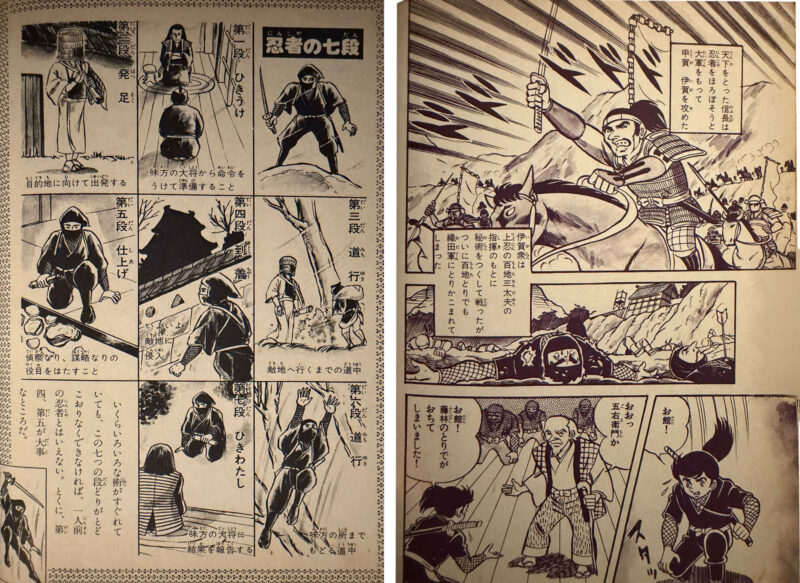

There were myriad artists involved with these books, with some outright manga depictions of famous ninja exploits and cartoon strips of espionage techniques.

And of course plenty of weapons and gadget photos, dojo shenanigans and museum displays. Some of these images crept into American books and magazines in the 80s, and as featured on Rob Tuck’s Critical Ninja Theory, so too did a LOT of the information, taken as historical fact.

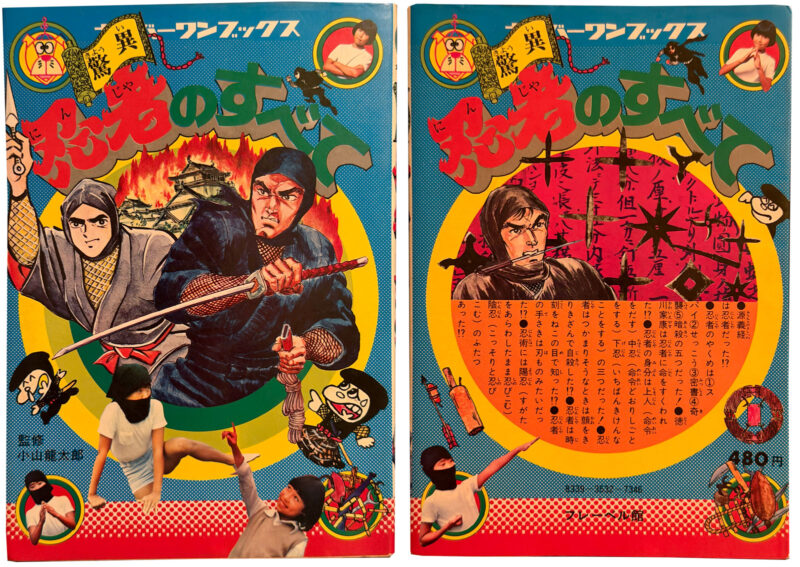

All About Ninja

Published in 1976, this 5×7″ 200 page gem from Number 1 Books, edited by Ryutaro Koyama, follows the example of the Hatsumi books, but is much heavier on manga short stories and leaner on dojo and museum display stuff. Definitely for a younger audience, it still pulls no punches.

Again, there’s lots of different art styles and tones throughout. Often it’s an artist riffing off of some other famed manga creator or cover illustrator. You see the stylings (and outright trademarked characters) of the likes of Shirato Sanpei and Mitsuteru Yokoyama but they were certainly not involved.

I’m betting this collects a lot of work published in various boy’s magazines of the 60s, shrunk down to pocket-sized.

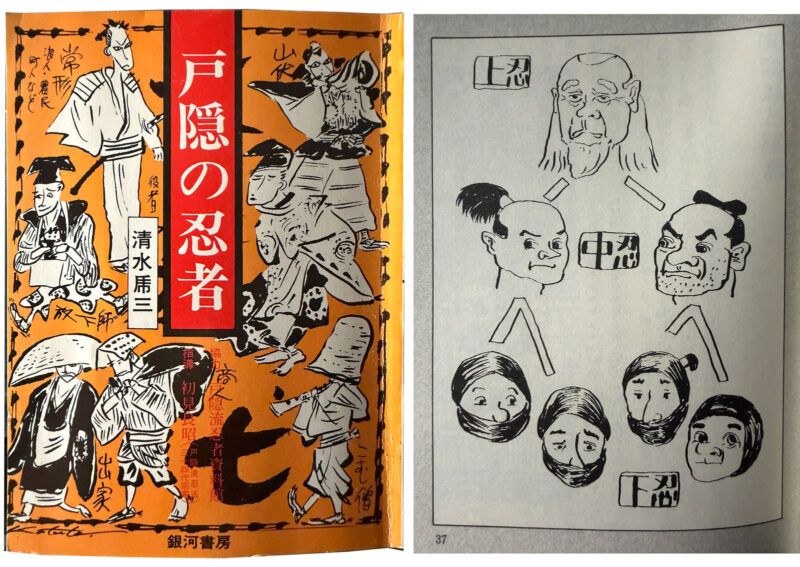

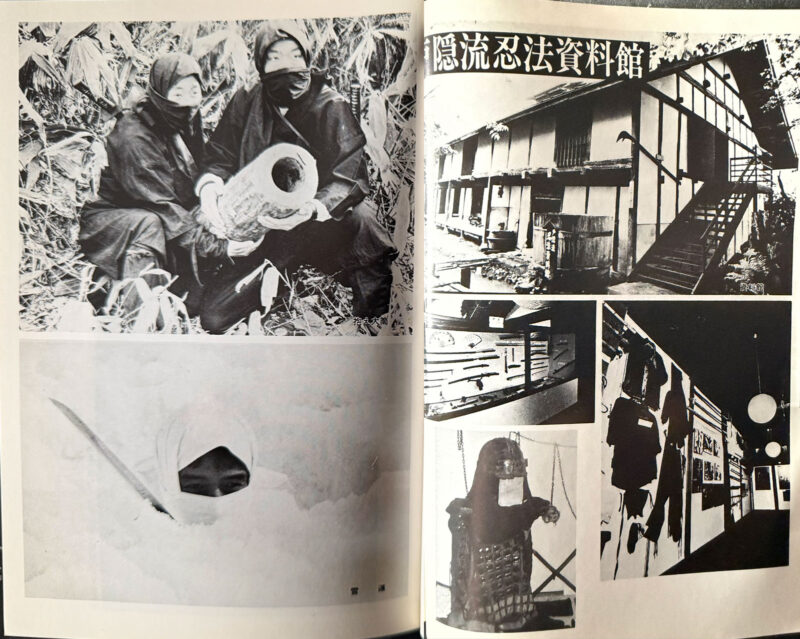

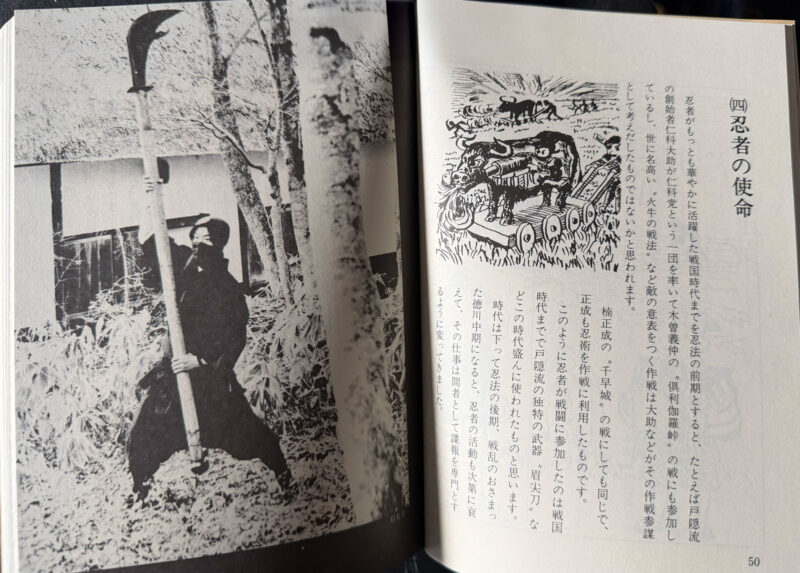

Togakushi Ninja

Originally published in 1982, and reprinted in a 200-page pocket-sized paperback in 2000 (my copy here), this work by Masazo Shimizu was done in cooperation with Hatsumi and the Togakure Ryu Ninja Museum. While covering much of the same ground, it stands apart from the above in having one single artist (whose credits are so buried I can’t find them anywhere) throughout, often replacing what would be photo matter or paintings in other books with abstract charcoal and brush doodles.

In general this has a more conservative and disciplined layout, likely aimed at older teen or adult audiences, in spite of the illustration style.

No matter how many of these books I flip through, there’s always one or two goofy weapons or techniques you’ve just never seen before…

AND HEY LOOK AT THAT! A ‘Kosugi Kick’ in a Japanese book!!!

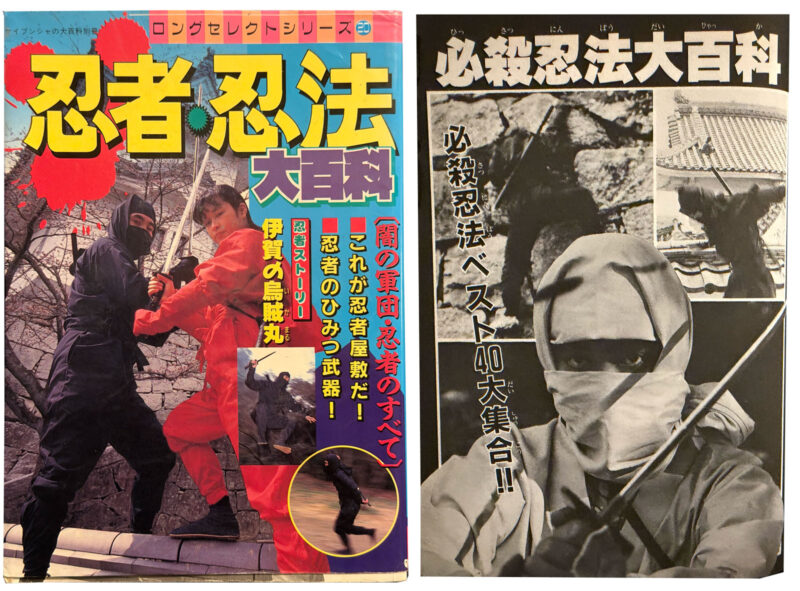

The Ninja Encyclopedia

Originally published by Keibunsha in 1983, then reissued with a new cover in 1990 (seen here), this 275 page 5×7 tome edited by Seimu Sakai is packed to the rafters in the finest 60’s boys-book tradition. Every spread is like an over-crowded Tokyo subway of ninja content, with multi-media executions living side-by-side the way they had two decades previous under Hatsumi.

Much of the material is the familiar tourist museum and dojo demo fare, and those spots were evidently barely updated in the decades since the 60s boom. But there are some 80s-looking ninja in here as well, and the movie stills do reflect some of the Cannon films from the States.

This one has more than usual glossy color signatures inserted, with some striking artwork. The editorial is the usual fare seemingly, although an appendix of popular ninja movies and anime is now a survey of retro media you might come across at a used bookstore or swap meet.

I just love that twenty years later a publisher heard that ninja were exploding in the US and abroad and cranked out a totally 60’s formula book in anticipation of another boom in Japan. Alas, despite many of the above books going back in print in one form or another, Kage no Gundan on TV and Kadokawa ramping up some special effects-laden shinobi cinema, the 80s never reached the heights of the 60s there.

Just Wait… There’s MORE!

The pool of vintage Japanese ninja books is DEEP, even six decades later and thousands of miles distant. I’ve got a few other books in the collection/library, and am about to self-gift a few more for my birthday in February, so you better believe my tax accountant— uh, my adoring readers — are getting a follow up to this feature… Stay tuned for more, and if anyone has some rare Japanese pulp they want to share, drop me a line!

Also, any time I feature old Japanese books, I always point back with thanks to Robert C. Gruzanski’s memorial site to the accomplishments of his father Ed.

Keith J. Rainville — January 2026