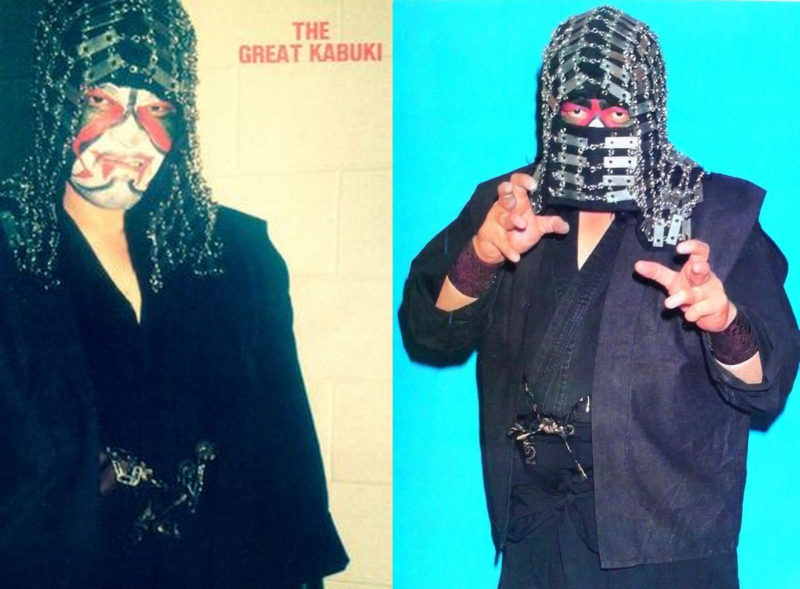

Akihisa Mera is a name unknown to most ninja-maniacs — he never starred in a martial arts film, was never featured in the pages of Black Belt, never consulted at a Bujinkan seminar. Yet he is one of the most significant ninja figures of the 80s boom, an absolute icon in his field and a testament to how far-reaching the ninja craze was into other entertainment avenues. Those of us paying attention to such things in that decade will never… EVER… forget Mera’s professional wrestling alter-ego — THE GREAT KABUKI.

Mera began wrestling in Japan as a teenager in the mid 1960s and toured the globe in the 70s to gain experience, eventually finding success in the Southern territories of the United States. Post WWII, Japanese wrestlers making careers in the West were too often saddled with characters like villainous judo or sumo masters using martial arts to cheat the rules of the wrestling ring. A lot of these same guys adopted the look of Odd Job from Goldfinger in the 60s, and all of those stereotypes persisted for decades. But in the 1980s, pop culture heavily fetishized anything Japanese, and ninja were about to become one of Japan’s most consumed exports.

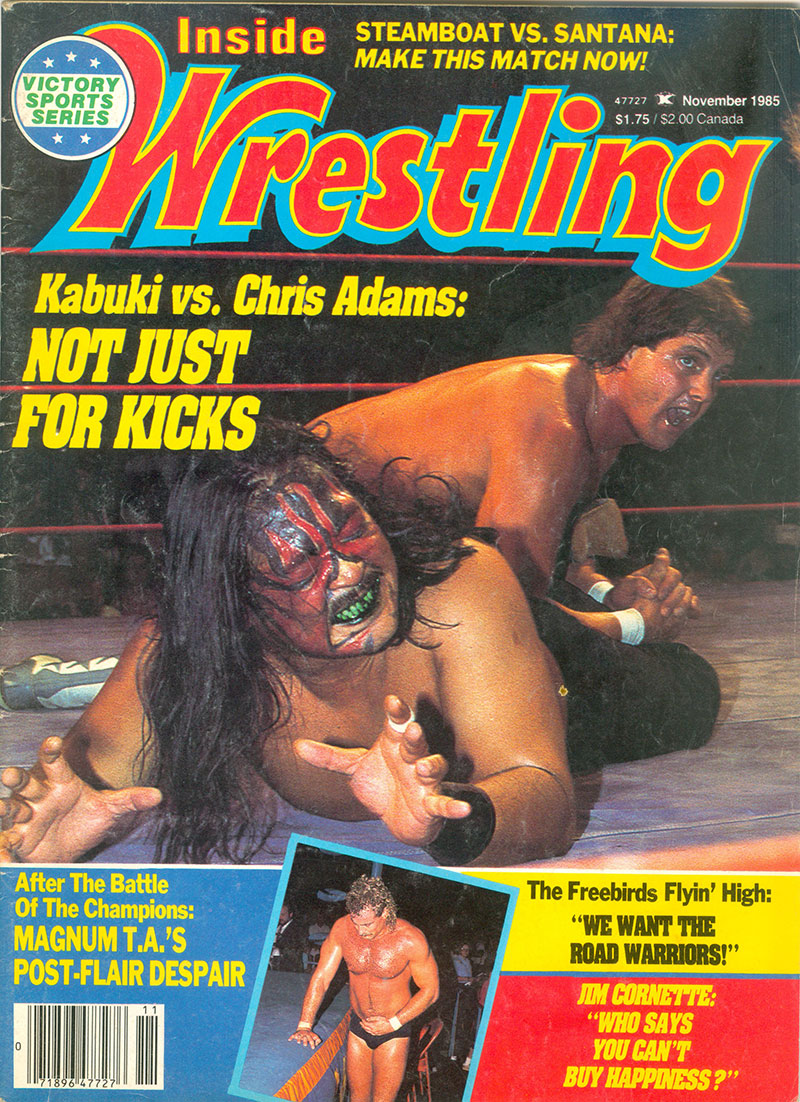

In 1981 — the same year as Enter the Ninja hit movie screens — Mera reinvented himself, trading wrestling tights and patent leather boots for Japanese hakama and tabi, came to the ring in ornate kimonos instead of ring jackets or entrance robes, and topped it all off with Noh theater masks or samurai helmets. When the headgear came off, it let loose an unnerving mess of long hair obscuring an ornately painted face — ostensibly to hide burns and scars suffered from Japanese death matches or arcane martial rituals. Kabuki (aka “Kabooki” to less literate promoters) was born.

“The Mystery of the Orient” or “Pearl of the Orient” persona was the co-creation of one of pro wrestling history’s greatest minds, Gary Hart. In a golden age of ‘heel’ managers (Captain Lou Albano, Freddy Blassie, Jim Cornette, etc.) Hart stood out as an importer of peculiar characters from far off foreign lands and unexplored corners of the globe (aka “From Parts Unknown”). His stable of villainous mercenaries included the likes of Abdullah the Butcher, Kamala the Ugandan Giant, the quasi-cannibalistic Missing Link, and yes, the hooded budo warrior Kabuki. Hart was, probably inadvertently, mirroring the character of Mr. X from Ikki Kajiwara’s seminal Tiger Mask manga and anime of the early 70s — a dapper gent hellbent on stopping a popular ring hero with an endless string of outré imported man-monsters.

Gary Hart, at his carney best, started dropping the term ‘ninja’ whenever he could circa early 1982, sensing the cresting wave of the boom elsewhere.

“What you see standing before you is The Great Kabuki! A master of all the martial arts… not just karate, gung-fu, zen… he is also a master of ninja style. You Oriental buffs will know what I mean, when I say NINJA STYLE!

This man comes from Singapore, and he’s in Texas for a purpose. And that purpose is to do what Gary Hart wants done to the people that he wants it done to.”

Hart was particularly gifted at “selling” the dangerous nature of his mercs — they’d be barely containable and prone to getting disqualified from sanctioned wrestling bouts by overly brutalizing helpless opponents. Broadcast hosts holding microphones for interviews looked genuinely afraid they’d be next. Hart always put on aires of being utterly exasperated from the effort of keeping his men on a leash (sometimes literally).

Kabuki was no exception. A nervous Hart would announce his man insisted on giving demonstrations of his martial arts mastery before engaging in a bout. Kabuki would produce a pair of sais, a samurai sword, or tandem nunchaku, hit some targets or slice up some melons, and then leer at the wrestler waiting to get into the ring. No one from wrestler to announcer to the old lady in the front row to Hart himself knew if those weapons were going to be unleashed on some innocent soul next.

What followed would hardly be called a classical wrestling match. Never the chiseled muscleman nor agile high-flyer, the somewhat doughy and technical grappling-limited Kabuki made up for it all via dramatic posing and sheer persona. He moved like a martial artist practicing kata in a dojo, until exploding into sudden fits of spastic spinning like something out of late 90s J-horror. He moved like no one else in wrestling, with exaggerated arm motions making common knife-hand chops look like the scythe of the grim reaper. His fingers were long and twisted like reptilian claws. His low spinning short kicks were superb and high long kicks knock-out blows. But as precise as his martial arts were, alternating bizarre trances and fits of anarchic rage were positively unhinged. The performer was a superb in-ring character-builder and storyteller, even without a mouthpiece like Gary Hart.

The “Dragon Sha” challenge was a Kabuki specialty — Hart would give a kendo bamboo practice sword to any wrestler up for it with the promise of a $100 reward if they could actually land a blow. Kabuki would adeptly block the stick with an armored glove for a while, then annihilate the poor sap in a burst of rage.

Then there was… the green mist.

Kabuki was never known for a specific finishing move like the Hulk Hogan leg drop or the top-rope “Super-Fly.” But he did come up with one unique bit that would make him a legend. As the pre-match rituals ended, he’d secretly break some sort of liquid dye capsule in his mouth and spit vibrant green mist on his raised hands, like he was Christening a ship with champagne. Hands and arms drenched, every blow he’d hit on a foe would leave a green welt, and he himself would be covered in overflowing verdant gore.

The mist would come back again at the end of the match, violently blown into the other wrestler’s face and eyes, causing immediate blindness and seizures. If the story called for it, the referee wouldn’t notice and Kabuki would score a pitfall victory as easy as a spitting cobra downing a field mouse… OR… the ref would actually be aware that one of the men in the ring had just been douched in green muck and was suddenly writhing around like a SWAT-team pepper spray victim and disqualify the villain. Audiences didn’t care either way, they just went bananas for the mist spot!

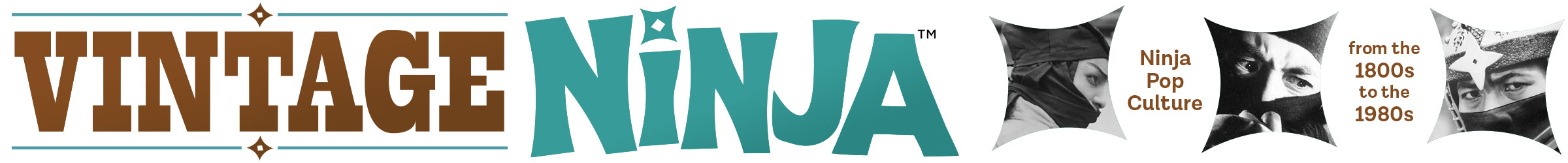

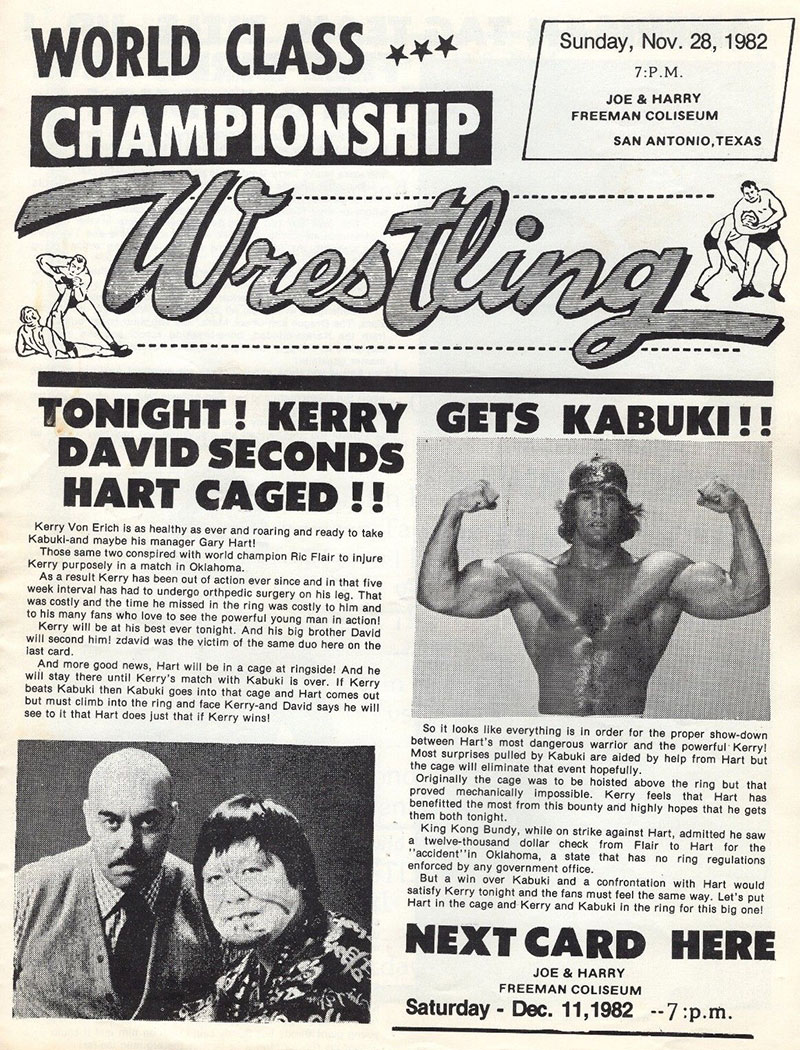

A life-long pro-wrestling fan, I first fell in love with Kabuki when he landed in World Class Championship Wrestling from Dallas,Texas. The WWF (now WWE) was getting too cartoonish as they took over the industry via national cable, so blood-thirsty pre-teens like myself who watched too many bad kung-fu movies as kids did the punk rock thing and sought out all the niche territorial stuff shown on competing networks — where wrestling was still dead-serious, brutal, violent and un-PC as hell. Hart unleashed Kabuki on the likes of the Von Erich brothers, Iceman King Parsons and a particularly memorable feud with Gentleman Chris Adams which culminated in a duel between the British star’s “Super Kick” and Kabuki’s “Thrust Kick.”

Seeing Kabuki for that first time was a real lighting bolt moment. My love of samurai and burgeoning awareness of ninja crossed streams with the over-the-top world of pro wrestling and shot right into my soul. And as if the Oni-masked Kabuki wasn’t cool enough, as the ninja craze went on, he dropped the theater costuming in favor of increasingly awesome martial arts gear, and for those of us who paid way too much attention to these things, none of it was off-the-rack from Dolans or Asian World, either! Particularly memorable was what became his signature plate-mail ninja hood, a prop in my opinion, superior even to what Sonny Chiba was wearing at the same time on Japanese TV in Kage no Gundan.

For this young ‘mark,’ Kabuki’s greatest moment would be a rare ‘face turn’ (becoming a good guy in rasslin’ vernacular). He disappeared from Texas rings for a matter of months, during which time blonde hottie manager Sunshine was continually harassed by gangs of bad guy wrestlers. Unable to cope with such an out-of-control environment, she held a press conference where her newest acquisition would be unveiled, a man she guaranteed would throw such fear into the evildoers afoot the scales of justice would be balanced in no time. As cameras rolled, an imposing black shadow stood like a statue behind her, finally revealed at the flick of a spotlight as the hooded ninja enforcer Kabuki! For those of us to whom WCCW was like church every Saturday morning, we utterly lost our shit. She went out and hired the most evil entity in wrestling to serve as her personal enforcer, like a one-man Magnificent Seven, and it was brilliant long-form story-telling.

By this time, Kabuki was full-on celebrated for his Japanese nature, and whether heel or hero, his Japanese-ness carried absolute cool factor. He took his dual nunchaku and smashed the stereotypes of the “Pearl-Harboring” Imperialist judo cheater, the evil sumo throwing salt in the eyes of good ole’ American boys, or the shifty Odd Job clone. Yes, these things persisted in one watered down form or another, but for the young audience at the time, we wanted ninja-infused pro wrestling, and The Great Kabuki did it the absolute best.

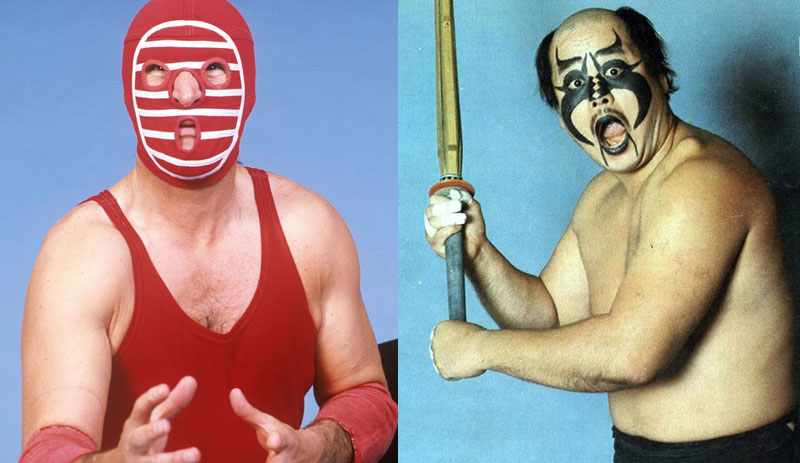

A slew of similar characters sprung up instantly, most notably Kendo Nagasaki (Kazuo Sakurada, not to be confused with the legendary masked wrestler from the 70s in Great Britain who despite being a weird white dude was a significantly ahead-of-his-time pioneer in the hybridizing of martial arts and pro wrestling), and mail-order ninja gear was often used to disguise domestic undercard talent as imported foreign exotics.

Kabuki would bring his American character back to Japan in the mid-late 80s, where he faced some of the top names in the business, including NWA Champion Ric Flair. He continued to wrestle in various companies — often getting disqualified for out-of-control antics — until retiring from regular active duty in 1998, but still doing occasional special attraction bouts until as late as last year.

Despite a few title reigns here and there, and memorable feuds with the likes of Dusty Rhodes, The Great Kabuki’s true legacy is his impact on other performers in the business. In 1989, Hart would pass much of the persona — the hoods and the mist in particular — to burgeoning mega-star Keiji Mutoh, aka The Great Muta — in wrestling storyline, the son of Kabuki. Mutoh originally cut his chops as the cheaply costumed “White Ninja” (even tag-teaming with Kendo Nagasaki) but post ninja craze, the now ‘Muta’ would drop the weapons demos and theatrical gimmicks in favor of more colorful paint schemes and a spectacular array of never-before-seen offensive moves that would make him a legend. He even upped the mist game by changing colors from pre-match to end.

Other wrestlers like Japanese-via-Mexico high flyer El Ultimo Dragon would adopt the mist, The Great Sasuke‘s mask mimicked Kabuki’s face paint, Jinsei “Hakushi” Shinzaki brought back the antique accouterments and wrestling style but this time in all white, and every vicious kicker in wide pants like Tajiri the Japanese Buzzsaw owes their signature style to Kabuki.

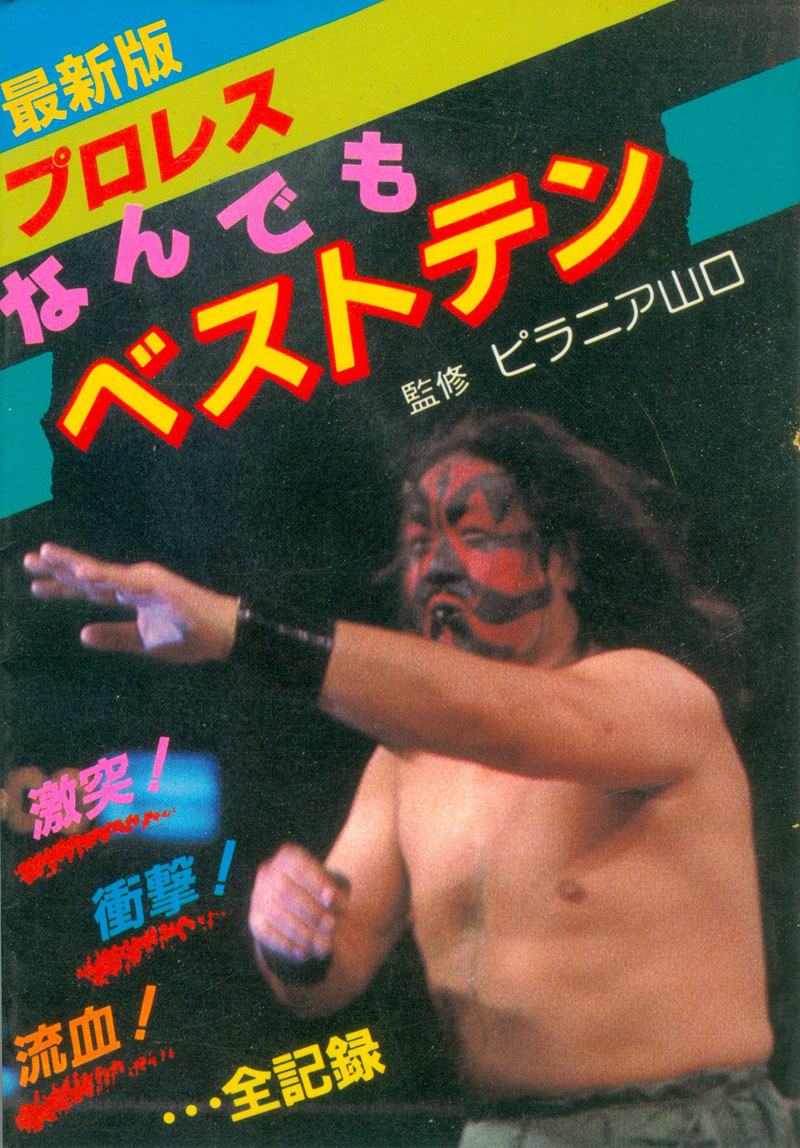

In the 2000s, Kabuki was finally recognized in some merchandise, amidst a wave of Japanese wrestling nostalgia.

The Great Kabuki’s formal retirement in December of 2017 was a touching affair — after a final ring appearance the aged legend blew green mist one last time, flipped the dual chucks then laid his weapons down in the middle of the ring amidst a downpour of celebratory streamers thrown from the crowd. I watched footage of this online with a bit of a tear in my eye, and endless admiration for his persistence in executing one of the finest characters the wrestling business — and the ninja business — had ever seen.

Keith J. Rainville — November, 2018