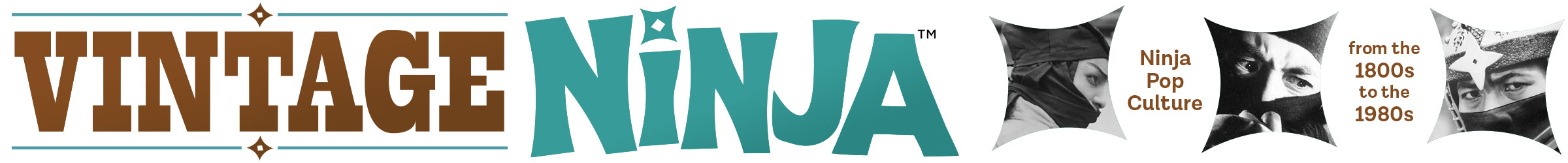

We’ve recently been blessed with the book Carnal Curses, Disfigured Dreams by Japanese cinema researcher Kigami Jigoku Kobayashi, and it inadvertently provided some jaw-dropping insight into the depth and breadth of ninja movies going back to the 1910s and how everything we’ve all been crediting as original to booms in the 60s and 80s actually happened decades before in remarkably similar fashion. Ninja were big business as the first celluloid was ever shot in Japan. But first, the book.

It’s a book about ghost movies.

Well, ghost movies, monster movies, mythical creature movies, cryptid movies and all sorts of weird f’d-up stuff the Japanese have always put on screen. There term is Kaiki-eiga — “bizarre films.” Unaware there was any tie-in to the history of silver screen shinobi, I bought this book solely for my interest in yokai and the Yokai Monsters films. I was aware such creature-centric films dated back to the silent era, but not how many existed and how multiple studios cranked them out in fierce competition with each other. What I was aware of though, is how most of Japan’s silent era films are lost to natural disasters and man-made wars, and therein lies the heart-breaking underlying core of this research effort…

It’s a book of the ghosts of movies.

Carnal Curses, Disfigured Dreams is like a war memorial to the fallen, a long scroll of the lost, a memory of something that can never live again. It’s an exhaustive list culled from the ledgers of film distributors and bills from studio and cinema accountants. Such documents yield titles and release dates and sometimes personnel – directors, occasional actors. From that compilation, the author tracked down whatever descriptions and details he could from reviews in increasingly rare aging newspapers and copies of movie magazines that managed to survive the quakes and the bombs.

The bulk of the book, therefore, is tantalizing long lists with frustratingly few synopses, flushed out with whatever publicity photos or advertising posters Japan’s National Film Archive and some private collectors could offer. Sadly, it’s not much. This is one of the most sobering lessons on the fragility of the silent age and how easily entire eras of cinema history can be lost to the modern world.

BUT…

An unintentional side benefit of the author’s work in cataloging year-by-year supernatural-themed movies is the surprising amount of things familiar to the shinobi-cinefile that show up – toad and snake magic, warriors using sorcery to transform or instantly disappear or teleport to other realms, etc. — you know… NINJA MOVIES!

Even with this woefully incomplete picture of an essentially lost era of film, even with the focus of the book NOT being a history of ninja movies, Carnal Curses, Disfigured Dreams is basically a chronology of the earliest ninjutsu in cinema, and just from the amount of titles, the studios involved and familiar names that are still showing up in ninja media today, one can put a skeletal account together of the earliest ninja stories, stage plays and even folklore that made the leap to the silver screen, and how clustered those adaptations were in their release patterns.

Jiraiya and Sasuke – the first multimedia ninja

Springing from the mists of oral tradition and tall-tales in 1806, an heroic shape-shifting ninja wizard named Jiraiya would use his toad-magic to battle the snake-magic of villainous Orochimaru in highly popular books and, perhaps more importantly, Kabuki plays laden with innovative stage effects and even giant monsters.

As Japan embraced the burgeoning art of silent film, it’s greatest amphibian kaiju-commanding shadow master was right there. The first adaptation — Jiraiya Goketsu Tan-Banashi — came in 1912. 1914 would see three different adaptations of the same character/story by rival studios, including a gender-flipped version. And additional remakes followed for years to come.

So yeah, exploitive knock-offs of ninja movies are nothing new…

These earliest of adaptations were largely efforts to capture the stage experience for a gimmicky new technology few at the time would have guessed would become so dominant in future decades. The sets were essentially play stages, the cameras centered and often dead-still. The cinema experience was augmented by live narrators, themselves accomplished performers belting out the stories and prompting crowd responses like carnival barkers.

1915 would see another manifestation of folklore via pulps and kabuki — Sarutobi Sasuke. Somewhat more ninja-like from our modern perspective than Jiraiya, the impish trouble-making student of a wise old mountain wizard lent early filmmakers opportunities to explore visual effects film could do more convincingly than stage — instant disappearances and pop-transformations into various magical creatures.

With the groundwork laid by the various Jiraiya and Sasuke films, the original ninja movie craze was on. Check out the density of titles and the competing studios (in parens) trying to one-up each other with tales of ninjutsu magic:

1912:

Jiraiya Goketsu Tan-Banashi — “Legend of the Hero Jiraiya”

1914:

Jiraiya (Nikkatsu)

Jiraiya (Tenkatsu)

Jiraiya O Teru (Nikkatsu) — female version of the same hero

1915:

Sarutobi Sasuke (Tenkatsu) — considered by the author the first outright ninja movie, as the Jiraiya character was often more of a swashbuckler hero who used some ninjutsu black magic, but ultimately won his fights with gallant swordplay. Sasuke kids books from Tatsukawa Bunko were hugely popular at the time, and this is likely an adaptation from the literary realm rather than the stage.

1916:

Jiraiya Goketsu -Den — (Komatsu Shokai)

1917:

Kintoki Kinta (Nikkatsu)

Nidaime Jiraiya (Nikkatsu)

Ninjutsu Botan No Choji (Tenkatsu)

Ninjutsu Juyushi (Tenkatsu) — likely the first adaptation of the ‘Ten Sanada Braves’ story

Ninjutsu Sanin Taro (Tenkatsu)

Tengu Sodo (Nikkatsu) – possibly ninja-related

1918:

Jiraiya Goketsu Banashi (Nikkatsu)

Sarutobi Sasuke (Nikkatsu)

1919:

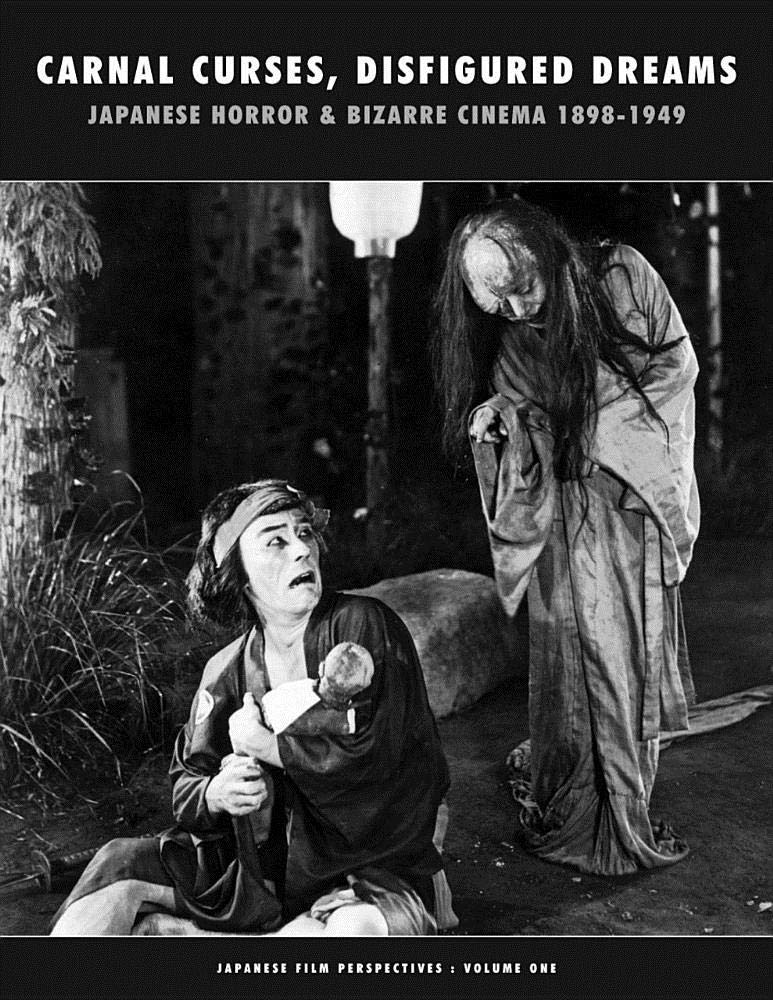

Amago Juyushi (Tenkatsu) – possibly the first kunoichi portrayed on film

Kaijutsu Ryuomaro (Tenkatsu)

Ninjutsu Shiteno (Kokkatsu) – launch of a new studio with a now reliable genre

Okubo Hikozaemon to Ninjutsu Yakko (Tenkatsu)

Onna Sarutobi (Tenkatsu) – gender-flipped Sasuke

Sarutobi Sasuke (Nikkatsu)

1920:

Genkotsu to Ninjutsu no Manyu (Nikkatsu)

Iwami Jutaro to Kirigakure Saizo (Kokkatsu)

Kirigakure to Sarutobi (Nikkatsu) – this and the above were competing films featuring the ‘Saizo the Mist’ character later portrayed by Raizo Ichikawa in middle Shinobi-no-Mono films

Ninjutsu Koboshi (Kokkatsu)

Sarutobi Sasuke Ninjutsu Daisakusen (Kokkatsu)

1921:

Goketsu Jiraiya (Nikkatsu) — this can actually be seen here!

Goto Matabei Ninjutsu-Yaburi (Kokkatsu)

Joso Ninjutsu (Kokkatsu)

Ninjutsu Goro (Nikkatsu)

Sanada Daisuke to Sarutobi Sasuke

1922:

Jiraiya (Shochiku)

Kirigakure Saizo (Nikkatsu)

Kirigakure Saizo (unknown studio) 3 minutes rumored to exist

Ninjutsu Sanyushi (Shochiku)

Sarutobi Sasuke (Shochiku)

1923:

Ninjutsu Gokko (Shochiku)

1924:

Sarutobi no Ninjutsu (Shochiku)

Gijin Sarutobi (unknown studio)

1926:

Ninjutsu Ichiya Daimyo (Nikkatsu)

Sarutobi Sasuke to Seikai Nyudo (unknown studio)

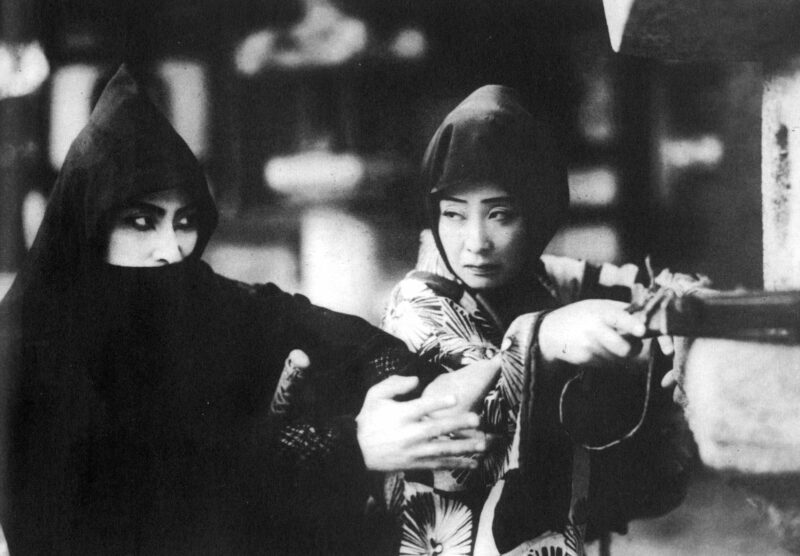

Despite upstart studio Shochiku’s best efforts, this initial ninja movie boom ended, but would rekindle a bit in a new form – early anime – in 1934 with the introduction of Fireball Boy in Ninjutsu Hinotama Kozo – Edo no Maki (Nikkatsu) with two sequels following in 1935.

Yojutsu Sharanui Kumo (1936) is described by the author as one of many lower-budget period films portraying ninja black magic, mythical creatures, shape-shifting and swordplay. I read this as ‘exploitation’ in all the best ways. Ninjutusu Togakushi Hakkenshi and Ninjutsu Yaoya Tanuki followed in 1937 with Kai Genma and Kaiketsu Tora in 1938 introducing concepts of skull-hooded villains and half-tiger ninja superheroes that would reincarnate and flourish on kids TV in the 1970s.

1938 would reportedly also see ninja cinema infused with a trend of portraying primitive robotics and mechanical gimmick prosthetic limbs with films like Muteki San-Kenshi and Tetsu no Tsume a year later, and ninja-transforming-creature (i.e. mystical raccoon) flicks like Ninjutsu Daishingun and Ninjutsu Hyakuju Gassen – an effort to fuse any successful kids fantasy genres into one successful mutt, culminating in a 1939 Japanese adaptation of the Chinese legend “Journey to the West” called Ninjutsu Saiyuki.

However…

Between a catastrophic earthquake in 1923, the fire-bombing of Japan’s cities in WWII, and a post-war period of censorship that lead to the destruction of myriad films with any sort of fight scenes in them, every film mentioned above was lost, save for fragments of two of the Jiraya films.

It’s just all gone. We’ll probably never see any of these films. Silent films in general are in a continual state of going extinct. Age alone has claimed a vast majority of the world’s reels. The survivors are either the highest profile star-driven classics (Chaplin, Keaton, Fritz Lang etc.) or those with miracle tales of survival where prints escape countries and are found in barns or vaults in continents on the opposite side of the globe (look up how close we came to the complete destruction of Nosferatu). Those happy endings are a lot less likely with the Japanese output of the same time. For a variety of reasons, international distribution wasn’t nearly as prolific as it was for Western countries, the chances of finding wayward prints that ran the gauntlet of time, disaster and neglect even less likely.

But from the ashes of this era, we shinobi-files can sift out some revelatory info. The silent era to pre-war ninja movie boom, portrayed here only in fragments of damaged film, scarce publicity stills, ledgers of distribution paperwork and scant surviving newspaper reviews, still provides some clear insights:

- Ninja were a significant component of Japan’s earliest popular cinema efforts, and there is a distinct glut of these pictures for about the same span as the Japanese craze of the 1960s and the American boom of the 80s.

- They effortlessly made the transition from stage and page to screen and afforded early experimental innovators with all sorts of special effects opportunities.

- Competing studios were instantly knocking each other off and exploiting each other’s successes in a Cold War arms race-style escalation.

- Ninja movies were inextricably connected to sorcery/magic, creature effects and otherworldly themes, even weaving their way into primordial mecha and transforming superhero themes.

- When adult-oriented films waned in success, more exploitive studios did well adapting the same themes and characters to kids’ fare.

From an admittedly under-informed perspective of a non-Japanese-reading Westerner, I had always viewed the post-war period of ninja movies as a decade of… hmm… sort of grasping at straws — adaptations of various folklore, 19th century pulp and stage properties making the jump to color film, with vague notions of more mature-themed black-clad commando action simmering under the surface and showing up once in a while here and there. Watching the few ninja films from the late 40 through the 1950s, they all felt old and dated. But knowing how prolific the ninja idiom was in silent film from day one, and how it was ALL lost, that 1950s period was clearly more about re-adapting old stories and characters to film again, just to have them to watch at all.

Here’s another nugget to chew on…

At the same time as this initial wave of movies, Gingetsu Ito was writing books informing a modern public on the martial history of ninja, and outspoken Koga Ryu ninja practitioner Fujita Seiko became a public figure with his first writings as well. Segments of the Japanese public — from kids looking for spectacle to adults curious about military history to the earliest movie-goers wowed by this new art form — were being addressed by various ninja media.

Martial arts and their masters coming into public light + movies on the silver screen + illustrated books in every kids’ pocket… sounds a lot like the 1960s and 1980s, doesn’t it!

The co-dependent relationship of ninja mass media and ninjutsu martial arts really has always been a chicken-and-egg deal, and more noticeably than ever, going back to the silent era. If it’s this apparent just from the skimming of titles from a book about ghost and monster movies, the imagination soars as to what else was out there at the time. You can just see kids playing ninja in the back yards of Japan a century ago.

Carnal Curses, Disfigured Dreams from Shinbaku Books is available on Amazon. It’s an 8.5×11″ paperback clocking-in at 140 pages, with a decent amount of photos considering how obscure and outright extinct the subject matter is. Highly recommended, especially for the creature-feature lovers. The same publisher/author combination is responsible for some nice genre poster books too under the series name Tokyo Cinegraphix. All worthy of your shelf.

And who doesn’t need some quarantine reading right now…

Keith J. Rainville — 5/6/2020

–