UPDATED!

We had some great response to this post last month, and since then another major find, so I’ve chosen to update and refine it a bit, and repost it as the start of a series of features on the storied and sometimes notorious “Ninja-To.”

Re-Enjoy!

Next to the black pajamas and the myriad shuriken designs adopted by ninja-craze merchants, there probably isn’t a more prevailent icon of 80’s shinobidom than the short-bladed straight-sword heavily marketed as the “Ninja-To.”

A long-handled, two-foot straight blade with plain square hand-guard, the alleged ‘sword of the ninja’ had a retro-fitted martial science all it’s own. The square guard could serve as a step to help you over walls, the sheath held hollow breathing tubes that could double as a blowgun and the end of it doubled as a spearhead or shovel. The un-curved blade was a necessity of the impoverished ninja villages where blacksmithing was much cruder. It also made the short sword easier to draw off the back. They were wielded reverse grip, a signature blade with a signature style…

Good as that all sounds, it is possibly all merchandise-inspired bullshit.

For starters, espionage arts are based on anonymity, so why carry a signature anything? Secondly, straight blades and reverse grips decimate the cutting power of a sword, why do that to yourself? And crude blacksmiths? Weren’t the same guys making all those other exotic assassination gadgets at the same time?

More to the point of this particular post, the popular version of this mass-produced 80’s sword always had shiny brass fittings, a bright-white handle with ornate cord wrapping, and a shiny-as-hell decorative silver blade. Real shadowy!

Regardless of its dubious at best historical pedigree, the Ninja-To was embraced by manufacturers and retailers because it gave them another version of the cheap and cheesy samurai sword to pawn-off on us martial arts marks (and before you ask, yes, guilty as charged, right here).

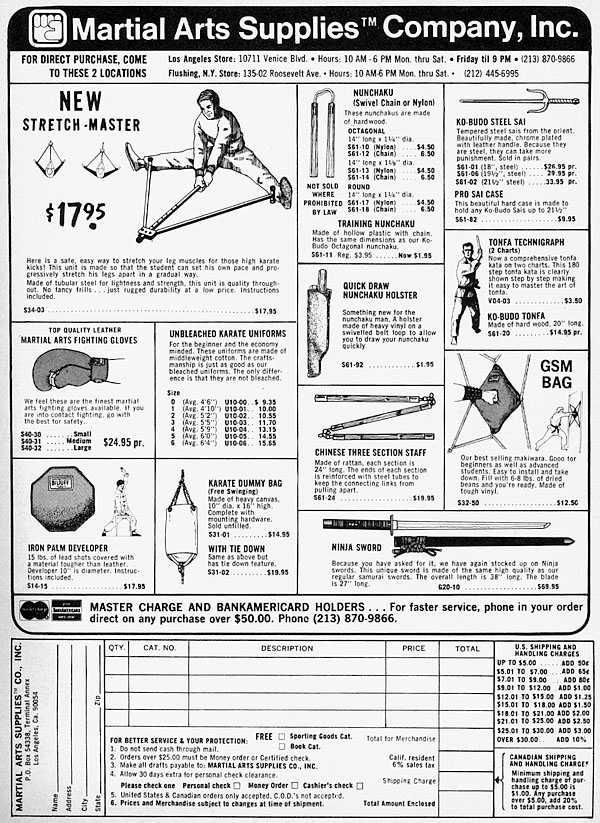

Tim and I were wondering just when this standardized “ninja sword” entered the retail vernacular, and I just found a pretty damn early mail-order ad for one in this 1977 issue of Black Belt:

Note the costuming on the cover – nothing off-the-rack here, definitely before the common mail order “ninja suit” became standard garb for such shoots. And although Stephen Hayes was becoming a fixture in these mags, the Kosugi-feuled craze was really three or four years away still. I can’t imagine we’ll find another ad a whole lot earlier. (See bottom of post!)

Also interesting to note the $69 price-point, which pretty much stood throughout the 80’s craze, and is still seen today in fact (guess inflation and changing world markets are no threat to the frugal ninja). There are cheap-as-hell sets of three you can score in any city’s Chinatown for $39, some “full-tang” display pieces of varying degrees of ridiculousness around that $70 point from online shops, and then a whole range of high-end stuff using the same design but with ‘battle-ready’ execution. You can see reviews of several superior-made versions of the this maybe-mythical classic at the Sword Buyers Guide.

UPDATE:

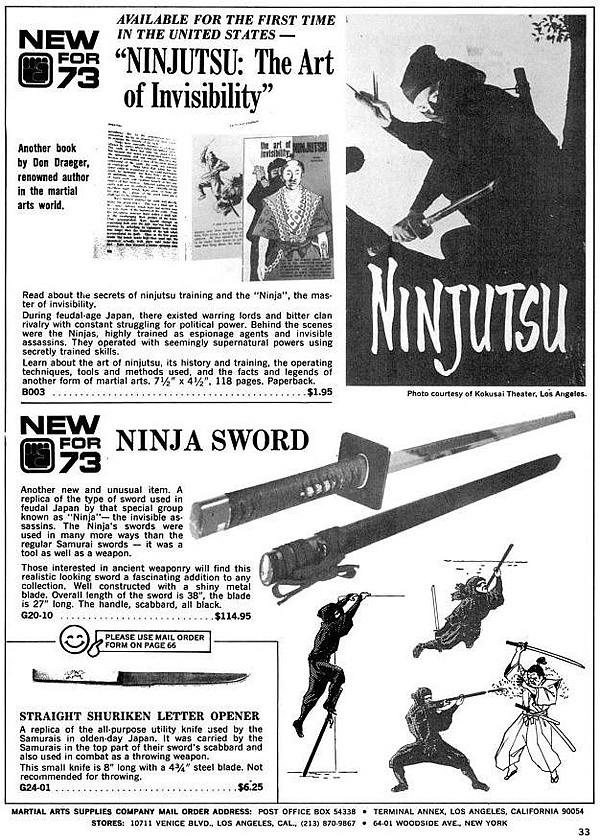

Don Roley at the BudoSeek info board, as part of an exhaustive post and series of over three dozen responses on the ‘Ninja-To’ debate found this ad from a 1973 issue of Black Belt!

Damn… 1973?!?!

Take a look at the sword, LOTS of conventions we’ve all previously attributed to the 1980s. And that photo is certainly from the 60s Japanese craze era. This Los Angeles importer was waaaaaay ahead of the curve.

3 Responses