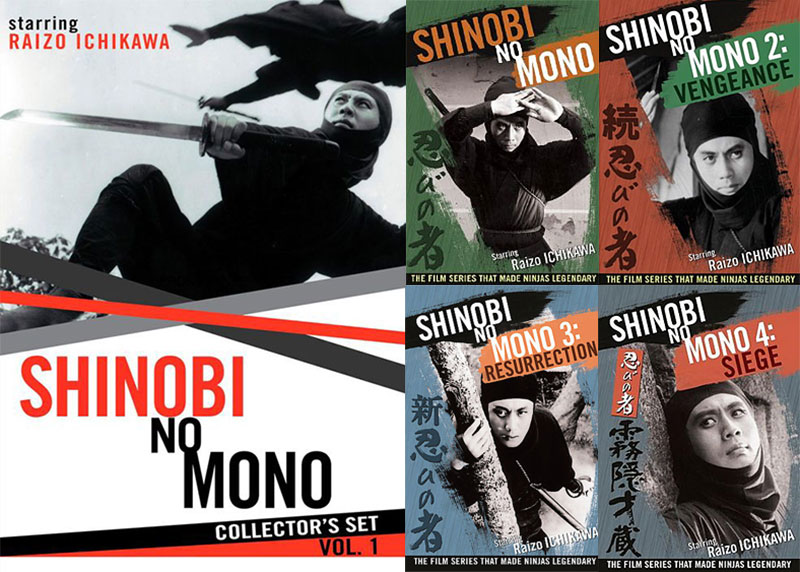

This week I was invited to be a guest on the NERD LUNCH podcast’s annual “Ninja Day” show. The usual panel of three hosts was well schooled in American ninja movies, but had never seen SHINOBI-NO-MONO, the ‘ground zero’ film of the original cinematic boom in Japan. So my role as invited expert became more one of missionary of the obscure.

The Nerd Lunch crew was impressed with the film, having the usual reaction of folks fist discovering the deep end (or high-end) of the the genre — an appreciative “Wow, there were GOOD ninja movies?!?!” exclamation, followed by a desire to see more.

You can here it all HERE:

Glad as I always am when I can share the ‘super-ego’ of shinobi cinema with those who only know the ‘id’ of exploitation, an always irksome question was brought up — WHY don’t we all know this movie and where was it in the 80s?

Frustration at discovering the depth of 60s ninja entertainment we were denied in the 80s boom was core to the founding of this site and all my subsequent efforts, so I truly welcome this opportunity to correct, albeit long afterwards.

So, the below article is intended as a intro to Shinobi-no-Mono for new audiences, and a companion piece to the podcast discussion on Nerd Lunch. And at the end tries to pinpoint why the Citizen Kane of ninja movies was never big deal in the States.

Enjoy!

SHINOBI-NO-MONO: The Lost Essential?

by Keith J. Rainville, December, 2016

New Decade, New Ninja

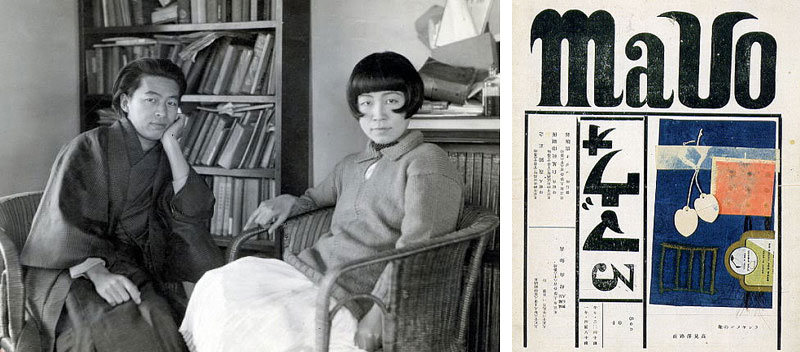

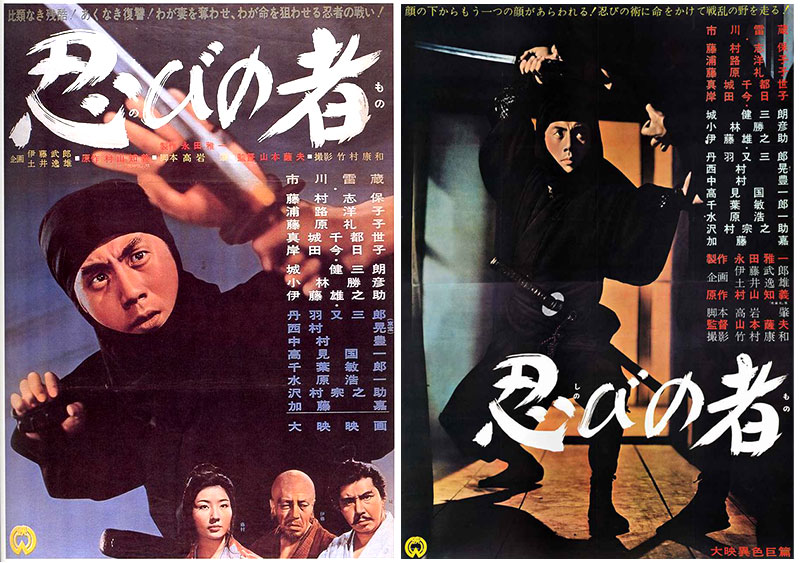

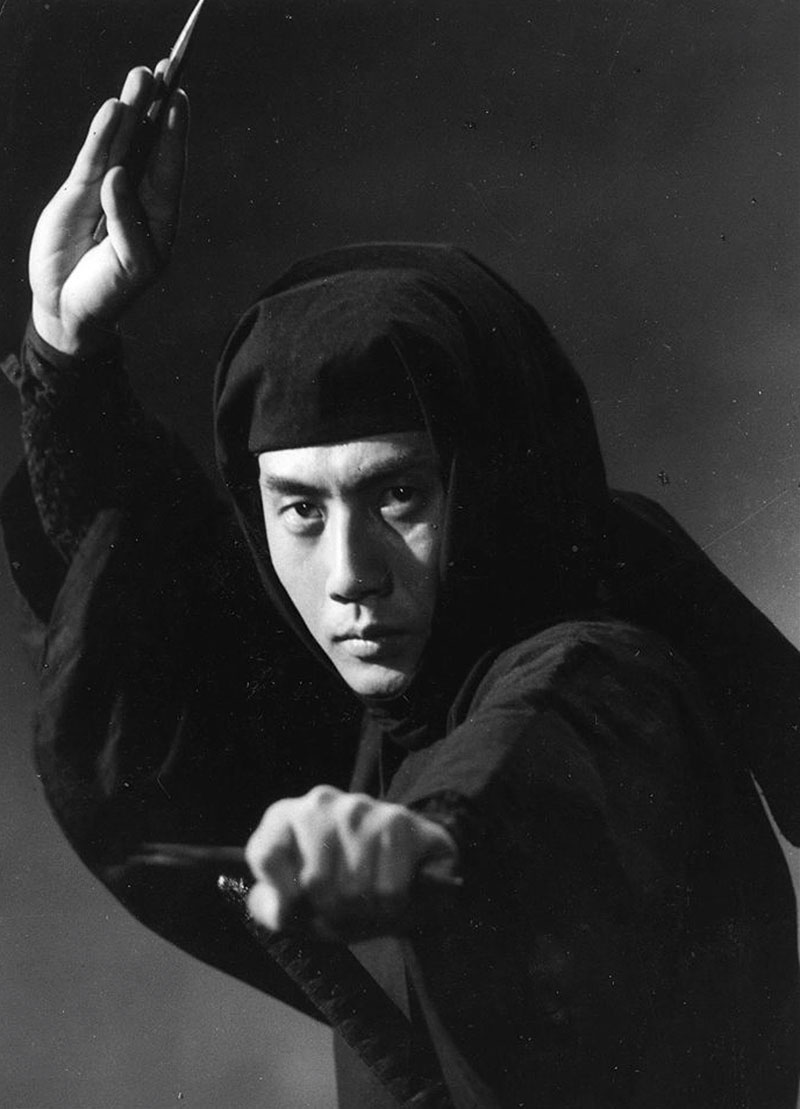

In 1962 subversive director Satsuo Yamamoto (known for his art group and publication Mavo as well as left-wing and anti-war films) and box office idol Raizo Ichikawa set out to tear the Japanese public’s idea of ninja movies a new orifice. Shinobi-no-Mono would become a hit for Daiei Studios, deconstructing the genre of colorful swashbuckling wizard-based ninja that had grown out of kabuki theater. Mirroring trends in popular literature and manga, SnM wasn’t the first black-and-white ninja movie featuring the hoods and commando techniques, but then again Dr. No wasn’t the first British spy movie of the 60s either.

Out were the magical special effects and jaunty heroes, in were gritty, realistic ninja films that saw socially oppressed little guys in black cloth suits with specialized shadow skills trying to shirk the foot of the armored spear-wielding samurai climbing over them for upward mobility. The Murayama Tomoyoshi pulp novels SnM was based on wore its socialist agenda on its sleeve, and director Yamamoto specialized in tales of anti-heroes subverting authority. Feudal warfare would stand-in for the capitalist system, conquest of land doubled for corporate greed, rival ninja were the guys in the next cubicle competing for what should have been your raise, and warlords played with innocent lives like the most jaded of corporate middle management played with careers.

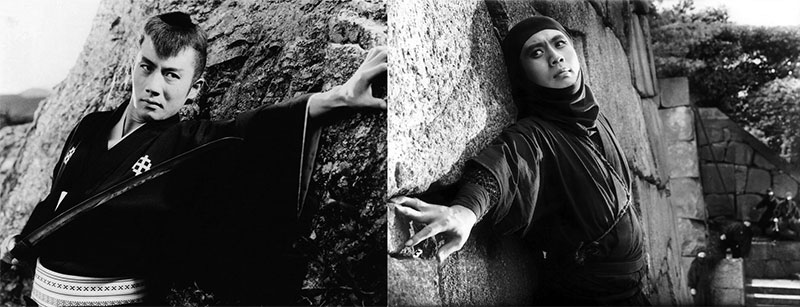

In addition to its socio-political tone, SnM looked like no other ninja movie had. Tomoyoshi’s books were inspired by the research of ninja history pioneer Heishichiro Okuse, and for the film adaptation modern ninjutsu practitioners Toshitsugu Takamatsu and Masaaki Hatsumi (of modern Bujinkan fame) were on set providing outré fight choreography. The new screen ninja they spawned fought different, crouched in unique stances, had unique ways of running, and in general moved and carried themselves differently than the samurai around them. Between the ninja advisors and credited prop masters “Kawaguchi Ryu” audiences were also first exposed to proprietary short swords, bamboo spy gadgets and most iconically, tighter, trimmer, more utilitarian black suits and hoods than previously seen.

The hills of Iga, previously portrayed as wooded paradises where white-bearded old wizards trained their plucky young wards in teleportation and weather manipulation, now became claustrophobic hiding places of secret garrisons that trained generations of spies, saboteurs and assassins in the dirty work richer, nobler samurai were unwilling to do. Prideful as they were in their astounding skills and reputations throughout the land, the farmer-class ninja villages of these movies were essentially ghettos, and were always the target of paranoid warlords unwilling to let the people of these provinces live by their own rules.

For the first time on screen the ninja life was portrayed as hard, unforgiving and spartan. There was no fame or glory for their anonymous work, no reward other than being the best and the secure knowledge that an otherwise impossible mission was executed by the only warriors remotely able. Withstanding torture and the resolve of cutting one’s face off if caught were skills taught alongside demolitions, exotic poisons and chemical weaponry. It was a grave, dark life with no upward mobility and the promise of an anonymous death in servitude to another.

A Story of Shadows

In addition to all of the shinobi genre deconstruction, the first SnM film was loaded…LOADED… with story, both sweepingly historical and intimately dramatic. The protagonist is Ishikawa Goemon (a real-life historical folk-hero / Robin Hood-type scamp / notorious serial criminal depending on myriad portrayals), a young and optimistic ninja of remarkable skill but flawed with ambition and a weakness for the ladies. Above him in the shadow clan hierarchy is his garrison’s chief Momochi Sandayu (another name plucked from foggy history), a grumpy and feeble ruler obsessed with taking down the brutal warlord Oda Nobunaga. Sandayu, however, is not all that he seems, living a double life as the more nimble (and horny) leader Nagata of rival garrison Fubayashi. This remarkable master of disguise is one of the most enigmatic and striking screen villains you could ever ask for. Sandayu plays his ninja groups against each other, two wheels in a revenge and greed fueled machine that grinds Goemon and every woman he’s connected with to a pulp.

Nobunaga, in the meantime, is rightfully paranoid about such a skilled people living beyond his control, and while Sandayu and Goemon play their little game of cat(s) and mouse, he’s winding up tens of thousands of cavalry, spearmen and artillery to level Iga the second he has an excuse to do so. A botched assassination attempt gives him just that, and all the best laid plans of mice and men meant nothing all along.

A-List All the Way

Goemon may be the lowly ninja hero fighting against an impossibly huge machinations, but he was played by anything but a lowly actor. Raizo Ichikawa is often referred to as the Japanese James Dean, being the looker who melted women’s hearts and had a magnetic screen presence, only to die too young of cancer in 1969. However his career spanned over 100 films, hardly the tiny sample of work of Dean’s that left audiences with the greatest ‘what-if’ in American cinema history.

Career-wise Raizo leapfrogged mega-franchise roles in eight SnM films and twelve Nemuri Kyoshirō (Sleepy Eyes of Death / Son of the Black Mass) adaptations the same way multi-franchise mega-stars like Harrison Ford or Sylvester Stallone alternated between Han Solo and Indiana Jones and Rocky and Rambo respectively.

And just like all of those franchises, Shinobi-no-Mono was A-list BANK. Yamamoto would return to helm an immediate sequel Zoku Shinobi-no-Mono, which was bleak as hell with a brutal downer of an ending that saw his hero come to the end history actually recorded — caught by the law and boiled alive in oil. But remember, ninja are masters of escape, and escape Goemon returned for a third adventure, followed by a series reboot as Raizo Ichikawa became “Saizo the Mist” for another four films. Meanwhile a concurrent 52 episode Shinobi-no-Mono TV series starring Ryuji Shinagawa aired by Toei in 1964-65, competing with the mega popular ninja-filled series Onmitsu Kenshin (aka The Samurai in Australia).

Every studio in Japan was cranking out ninja movies by mid decade — derivative noir-ish fare and gorgeous color adventures, kids’ manga adaptations to experimental art-house to soft porn. The movies and TV fed more and more ninja manga, which led to toys and merchandise, and interest increased in tourism to historical ninja locations with new museums popping up, martial arts manuals littered the shelves, dojo business boomed — it all fed each other and snowballed.

As the series went on, the grave, morose plots and socialist agendas took a backseat to lighter-toned action spectacles, more ‘black-suit’ time on screen than melodrama, and increasing emphasis on gadgets and arcane commando techniques. Screen ninja were being codified and the formula just kept selling.

An eighth theatrical SnM film would see Raizo return as yet another hooded hero in 1966, but this reboot was never followed up. Raizo Ichikawa would die of cancer in 1969.

New Decade, OLD Ninja

Daiei Studios, trying to extend the 60s craze into the 1970s, sort of rebooted the series yet again with a film called Shinobi no Shu (aka Mission: Iron Castle) — sometimes billed as the ninth film, sometimes not considered part of the series at all. Ill-timed with the dawning of the new decade, and ill-advised in invoking the franchise name soon after the nation’s heart was ripped out by the death of its beloved screen icon, the film failed to swell the mega audience its predecessors did, and fell into obscurity even among fervent collector circles for the longest time. But removed from that context, Mission: Iron Castle is arguably one of if not the best isolated examples of grim and gritty black-and-white ninja shinobi cinema. Prolific screen legend Hiroki Matsukata leads an elite band of ninja to rescue a kidnapped noblewoman from an ingeniously ninja-proofed castle loaded with traps. It’s wall-to-wall action, bolstered by familiar themes of wanting to escape the shadow life but knowing you never can, followed by a noir-as-hell ending. Just great.

But it was 1970, and everyone wanted color movies, and Raizo was dead…

Daiei would go bankrupt within a year, and the original Japanese ninja boom was essentially over.

So why?

Shinobi-no-Mono‘s reach went further than Japan, and much further than the 60s. British writer Roald Dahl cribbed several scenes from SnM for his script for the Bond film You Only Live Twice — the western world’s first cinematic exposure to the idiom. SnM‘s costumes, sets and ninja techniques (both martial and cinematic) were dusted off for 1980’s Shogun mini-series. Then a man named Sho Kosugi, who as a kid watching Shinobi-no-Mono was taught every lesson he’d need to know, came to America and became the icon of an entirely new ninja craze.

But during that mega boom in the U.S. and the rest of the world, the seminal Shinobi-no-Mono itself was largely unseen, and for all purposes “lost” to a potential international audience, as were the rest of its gritty black-and-white ilk. These movies sat in a distribution no-man’s land in the early 1980s. In a decade of garish neon color and post-Star Wars special effects excess, no English-language home video label was looking for something as complex, heady and monochromatic as SnM. But at the same time, an art house distributor like Janus Films, who’d scoop up any back catalog of Kurosawa, Inagaki, Ozu, Teshigahara and any other Japanese cinema elite wasn’t going to touch anything to do with “ninja,” as Cannon had placed the genre firmly in the exploitation/grindhouse camp, and cartoon turtles were on the horizon.

So instead of getting the best the original genre had to offer in English, we got a small, weird assortment of imported titles that looking back now makes no sense. There was no subtitled Shinobi-no-Mono, no dubbed Castle of Owls or Warrior of the Wind, no airings of The Samurai on late night cable. Instead, an illogical assortment of special effects epics (like Kadowkawa’s Iga Ninpocho — ironically a return to pre-60s ninja wizardry) were dubbed and given new titles like Ninja Wars, Legend of the Eight Ninja and Renegade Ninjas. Largely bereft of the black suits and signature arsenals we’d been trained to expect by Kosugi and Dudikoff, these outré Japanese films didn’t exactly whip up demand for the older stuff either.

The English-speaking world’s best exposure to SnM wouldn’t come until the early 2000s when bootlegged Japanese home video releases subtitled by fans in homemade DVD sets were gobbled up by people like, well, ME. Sadly, this piracy took the wind out of the sails for the superb efforts of Animeigo years later, whose officially licensed and superbly restored DVD boxed set of the first four movies evidently didn’t sell enough to merit the rest of the release of the rest of the films.

And now what?

There are now more years separating the 1980s American ninja boom films from a modern audience than there were years separating us 80s kids from the 1960s Japanese originals. So now that it’s ALL vintage, all antique media from an arcane decade, I wonder if new viewers will find the old films more — or maybe less — alien. Both decades’ product are equally available streaming, subtitles have conquered the language barrier, and newer properties like Naruto have actually expanded the public’s definition of ninja to include both the old models of magic spell-casters and the black hooded commandos alike. Maybe an old black-and-white movie about Sarutobi Sasuke would be more interesting to a Naruto-literate populace than it would have been to us in the 80s who just wanted to see ninja stars thrown into people’s eye sockets? Or maybe the current fetish the younger generations have with the ‘retro 1980s’ will make that decades’ ninja-sploitation even more delicious than it was back in the day?

My hope, as always, is that BOTH the 60s and 80s flavors find new audiences and an ongoing appreciation.

There’s no better place to start than Shinobi-no-Mono.

KR