Comic books never get enough credit for being the vanguards of entertainment movements, and their contributions are almost always overlooked in comparison to the big, break-through movie or TV show. But comics do two huge things that really lay the bedrock for booms to come — they make literate a young generation on something yet to be a household word, and secondly, feature the research and vision of creative types that seeds future creative types higher up the mass-media food chain.

For our purposes here, comics introduced the Western world notions of masked/costumed martial artists (a good decade and a half before the Shaw Bros. unleashed The Five Deadly Venoms), and of ninjutsu masters, to generations of (at the time) kids of the 1960s who weren’t reading Black Belt and ilk or old enough to see You Only Live Twice in the theater. Some of those kids would later go into the comic book industry themselves, so twenty years later ninja were in the quiver so to speak of Marvel and DC creative teams.

A key example of one of these unsung heroes of the ninja boom’s pre-history is the short-lived Judo Master.

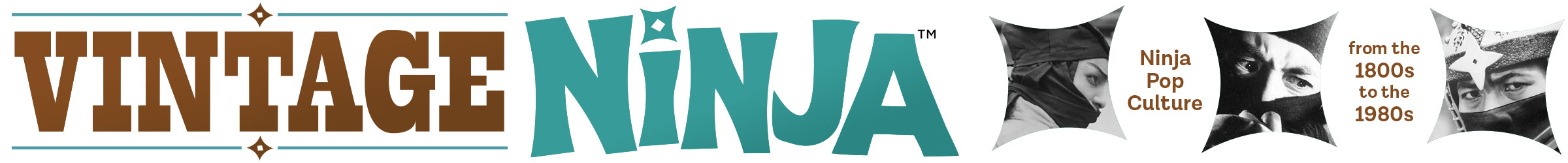

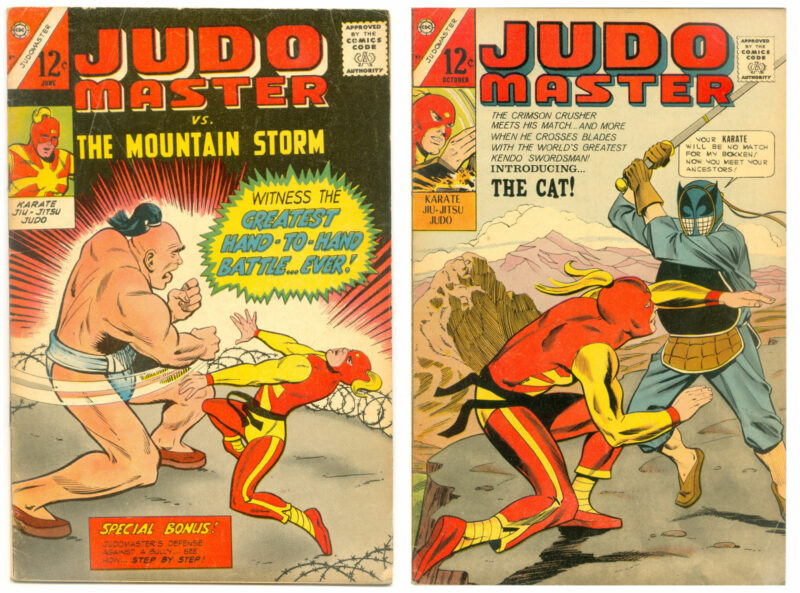

Created by the prolific Joe Gill and writer/illustrator Frank McLaughlin, a long-time martial artist and enthusiast of Eastern combat traditions, “Rip Jagger: Judomaster” (the title name and character name tend to flip-flop between one and two words) first appeared in November of 1965 in the fourth issue of a military-themed anthology comic called Special War Series from Charlton Comics. Charlton was one of many RC Cola-equivalents to the Coke and Pepsi that were Marvel and DC, and would later be bought out by DC for its bank of character rights.

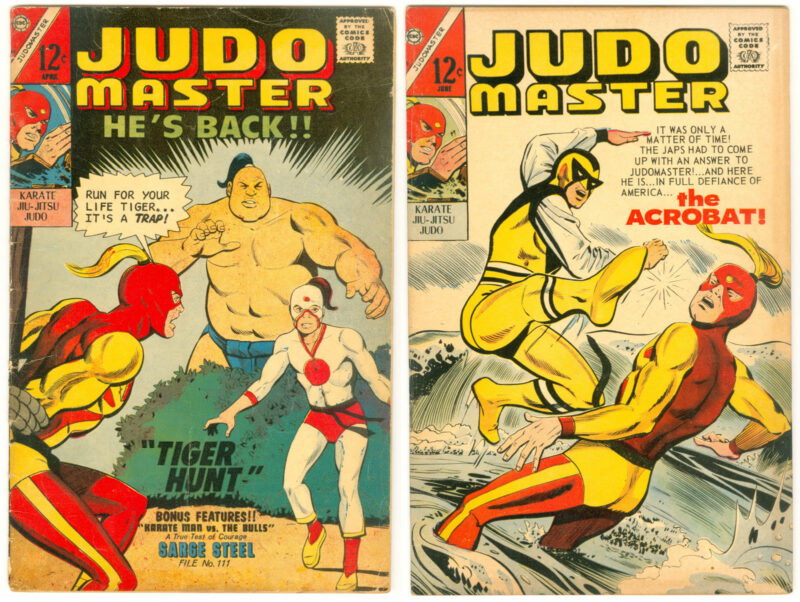

McLaughlin, the company art director, did like most creative types and put a lot of himself in his fictional babies. He had been creating short back-up features in the post-war spy comic Sarge Steel, featuring histories of various fighting arts and self-defense how-to lessons, but now jumped into the fray with a pioneering martial arts superhero.

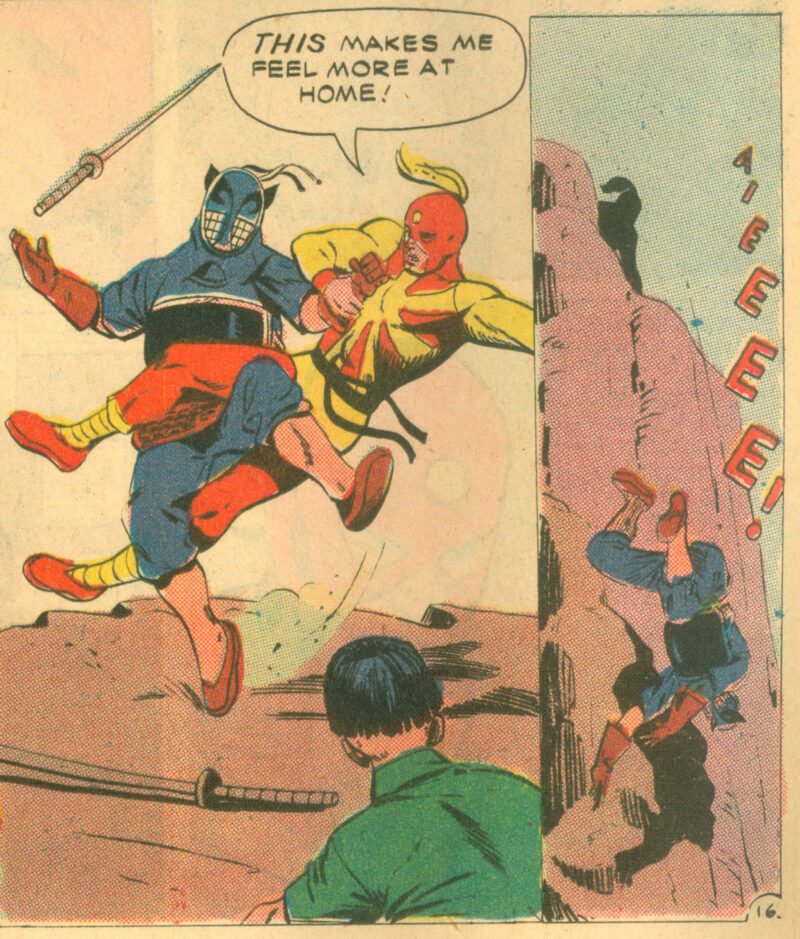

Judo Master was absolutely a product of its time — a two-fisted soldier fighting in the Pacific during World War 2, created by someone who himself had been in the army. When he encountered all that ‘Oriental chop-sockey’ stuff, he liked what he saw and of course became a better practitioner of it than any native-born life-long Asian warrior could ever hope. The attitudes towards the Japanese as categorical villains, and cringeworthy portrayals of them as yellow skinned simpletons, sometimes buck-toothed even, were inevitable. Other dyed-in-the-wool tropes of the day, and the comic book industry — “Mighty Whitey” characters being better at a foreign culture’s thing than anyone actually of that culture, putting teenage kids in danger as costumed sidekicks, etc. — just came with the territory.

But within that now-regrettable framework, the fact that Judo Master’s Japanese-based fighting skills were always superior to any sort of traditional American fisticuffs, and that he adopted the once-taboo Rising Sun graphical motif of the costume, bespoke of an underlying respect for the material and was actually somewhat groundbreaking. This was one of the earliest examples of “Japanese Cool” in a way.

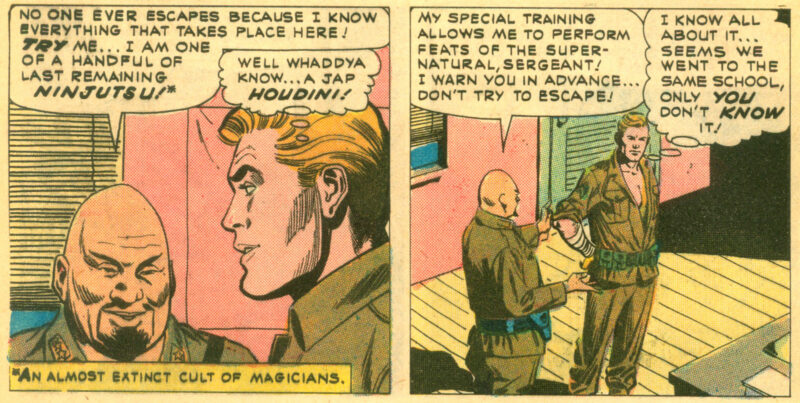

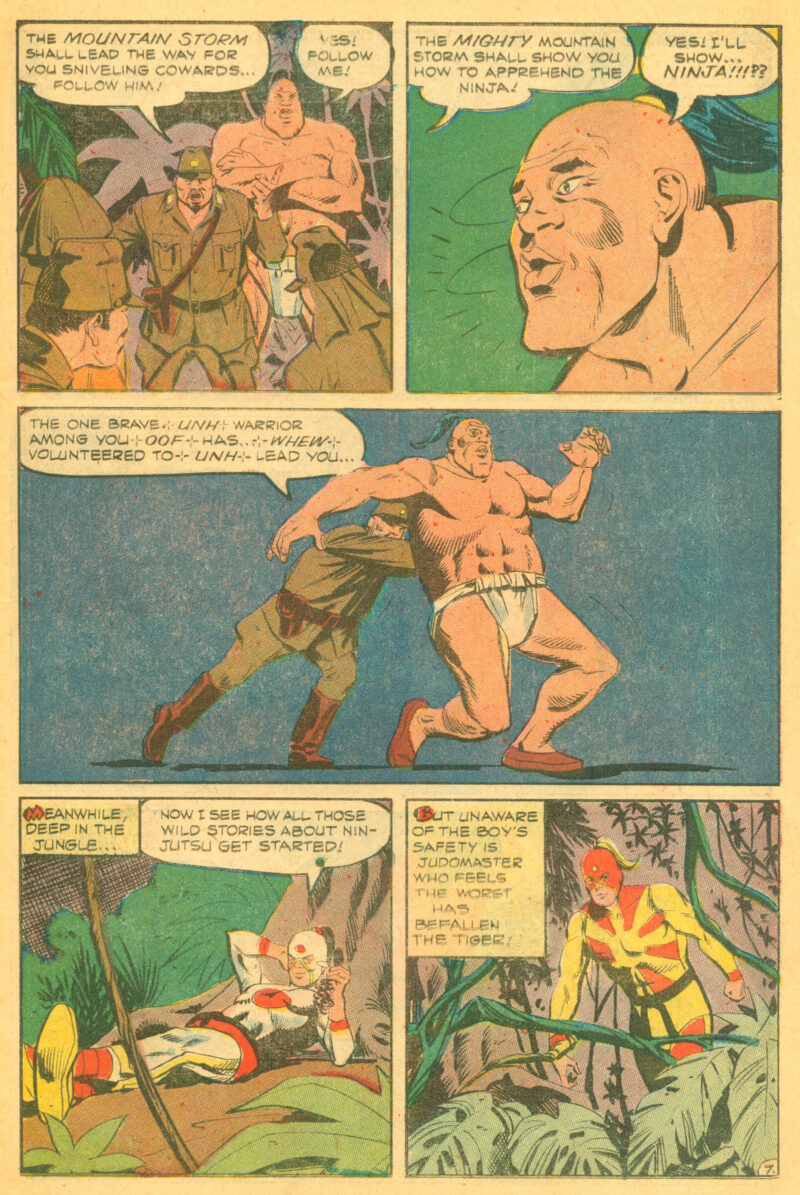

But… it is hard to read stuff like this and not shake one’s head:

That right there is likely the very first mention of ninjutsu in an American comic book. While earlier in the decade, You Only Live Twice was in print as a novel worldwide as well as newspaper comic strips in Great Britain, and ninja-themed articles had appeared in magazines like Argosy and books like Jay Gluck’s Zen Combat, the above panels from Judo Master #89, dated May-June 1966, popped the cherry for a generation of American comic book readers.

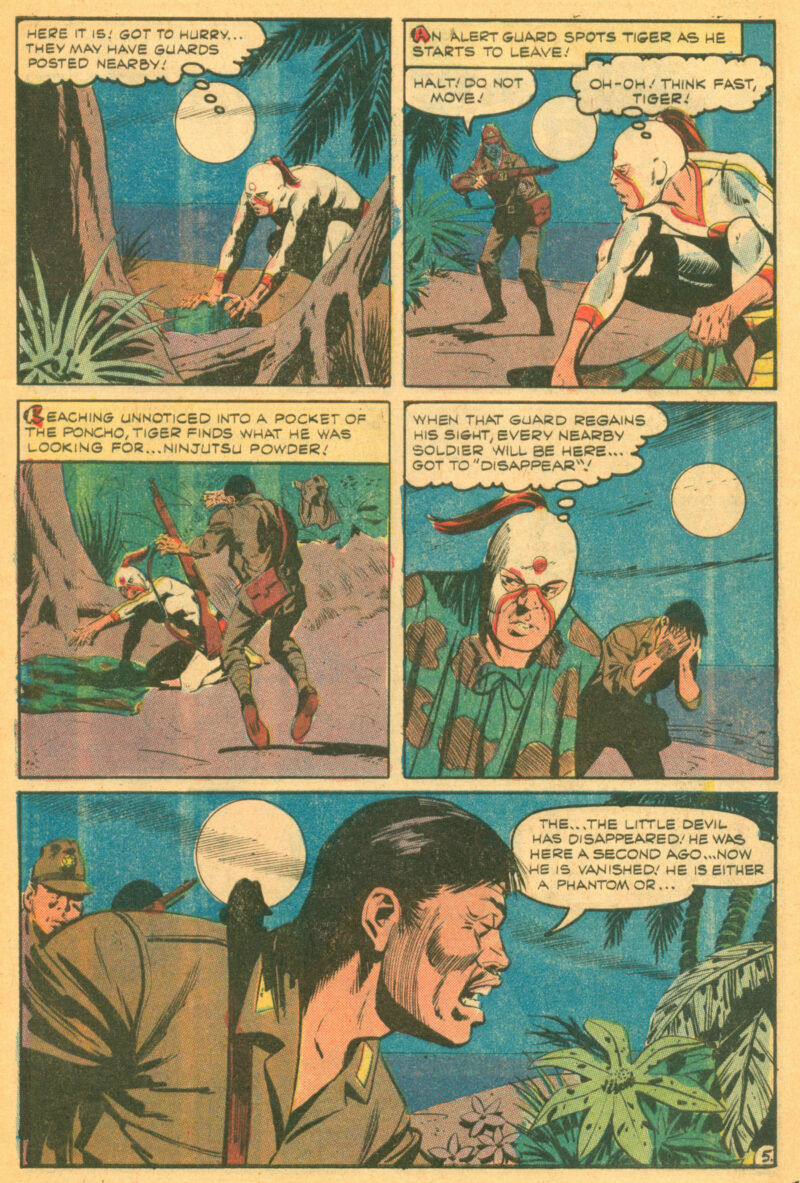

McLaughlin revisited the concepts of ninja a few issues later (#94 – April 1967), focusing primarily on primitive legends and superstitions still being current in mid-40s Japanese culture.

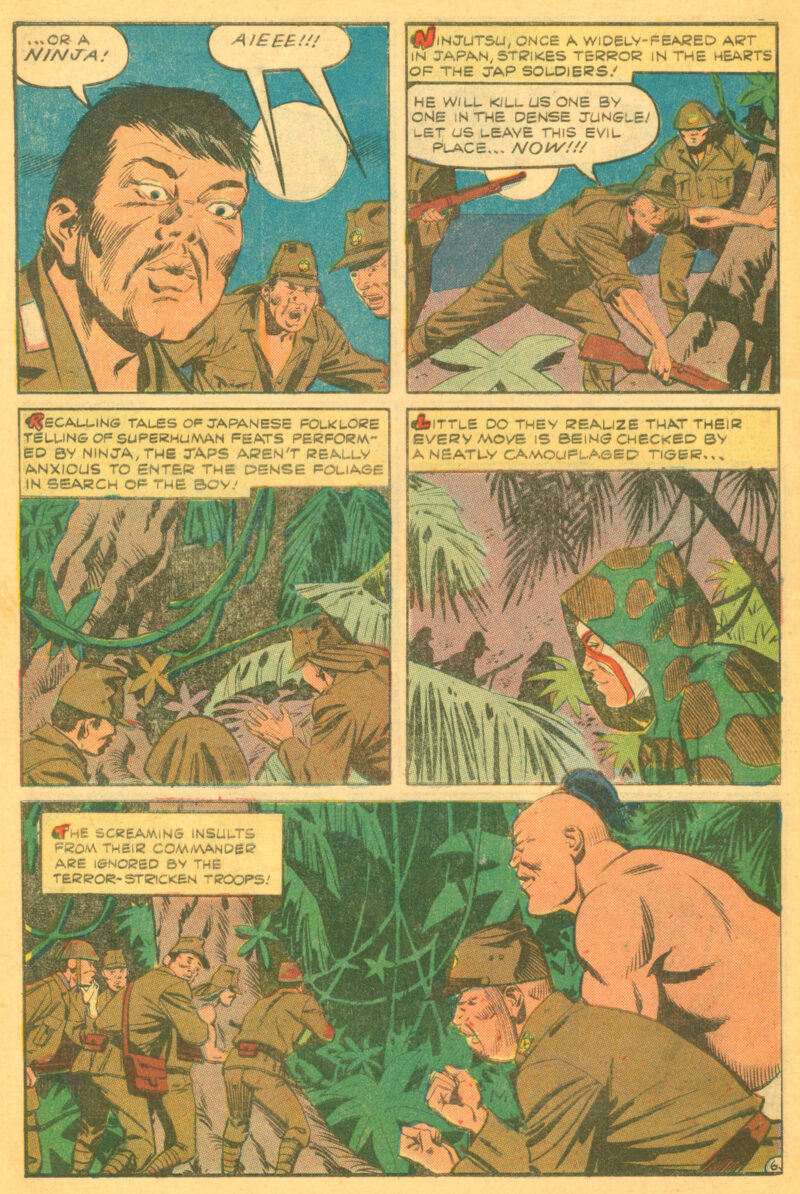

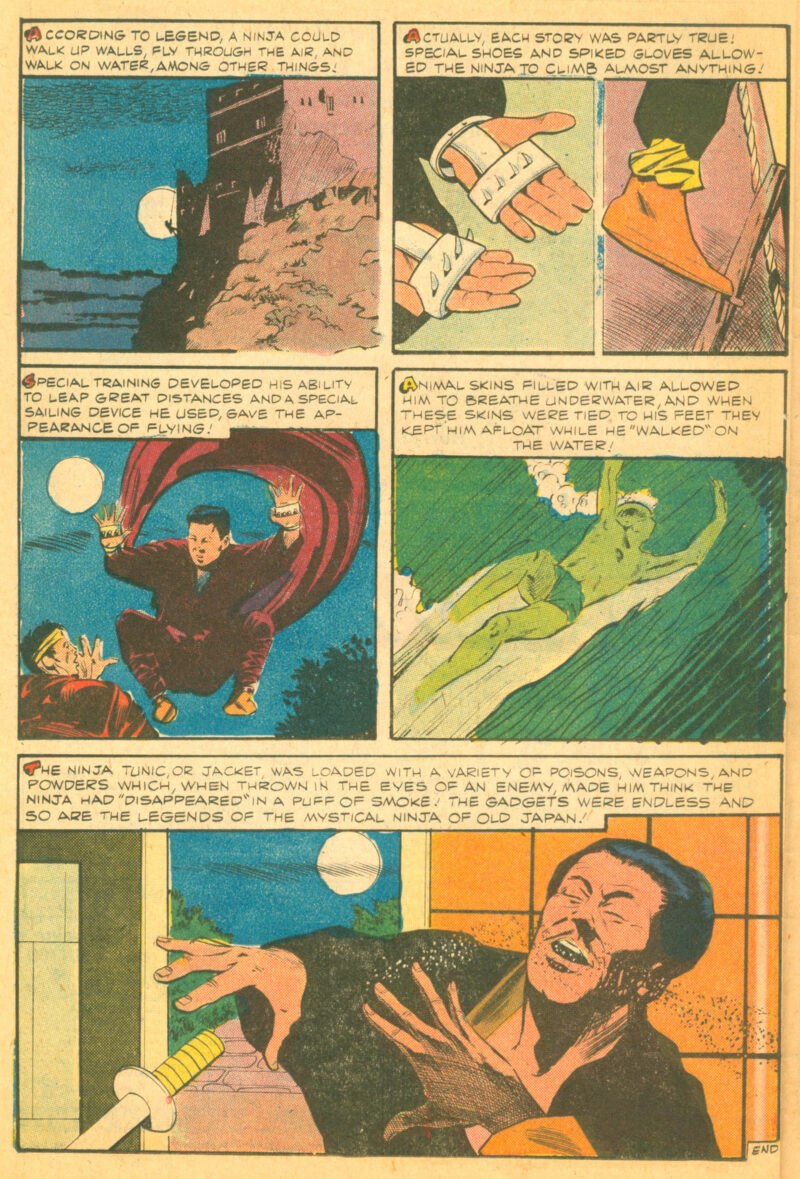

Then in June of 1967, with six months of Andrew Adam’s breakthrough articles having appeared in Black Belt and You Only Live Twice about to hit movie screens, McLaughlin created this two-pager which showed a marked improvement in the depth of knowledge and perspective, albeit sourced from hot-and-cold running visual reference.

Despite looking more like a Franciscan monk or a Jedi than what we’d come to know and love a ninja (although the costumers on The Octagon must have had this on hand?), some of the below is clearly from a qualified Japanese source:

Judo Master was cancelled at the end of 1967 alas, with the company on the rocks. The company held on by fingernails until the early 80s, when it’s “universe” of characters was bought out by DC, originally with the intent to be killed-off in a new meta-aware mature-readers series centered around commentary on the superhero idiom itself. But when the bean-counters saw the potential of characters like Blue Beetle, they held the copyrights for later exploitation and gave Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons carte blanche in creating, yes, The Watchmen.

But while Judo Master was saved from being newly portrayed as a sexual impotent with a mask fetish ultimately disintegrated by one of his own teammates, or whatever, it seems the character was just too dated to thrive various flirtations with rebooting in latter decades. Just as Bruce Lee was redefining martial arts in popular media, Marvel took the lead on martial-supermen with cinema-inspired heroes like Shang Chi Master of Kung Fu and the Judo Master-like Iron Fist (each facing various easily-disposed-of ninja characters throughout the 1970s). DC’s own WWII-era ninja Kana would follow, while Frank Miller would solidify ninja-cool in comics with The Hand in the pages of Daredevil and Storm Shadow would steal the show at GI Joe.

But none of that would have happened without the groundwork laid out by the largely unsung journeyman efforts of one Frank McLaughlin in the pages of Judo Master.

Keith J. Rainville — May 2019

Special thanks to David Goode for the assist with this piece. Check out his and Vance Copley’s Goode Stuff blog and copious Facebook posts encompassing multiple hero-centric genres.