Dateline: Hollywood, CA — 9-14-2014

It’s not often I talk ninja cartoons with college educators, but today was the exception.

Jonathan M. Hall, a Japanese film scholar from Pomona College screened three episodes of Shirato Sanpei shinobi TV treasures at the storied Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood as part of the LA Eigafest film festival. Interesting crowd primarily of academics, and me as probably the biggest ninja nerd in the room. Come to think of it, I’m usually the biggest ninja nerd in the room regardless of circumstance.

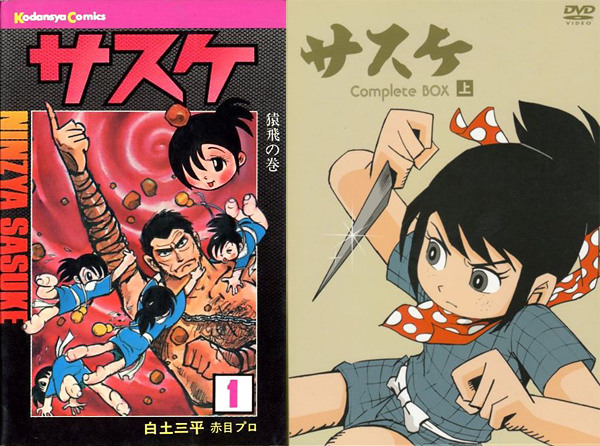

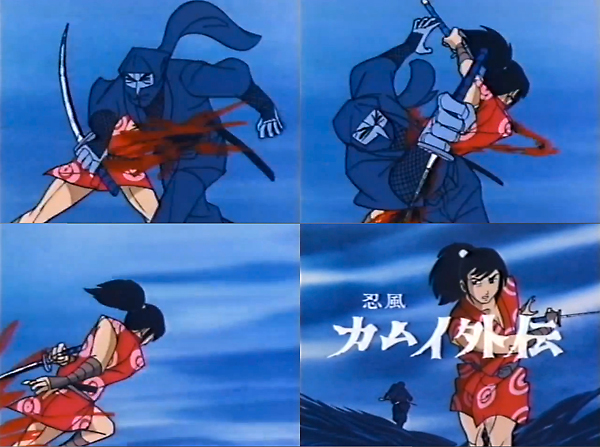

Anyway, there I am seeing two episodes of Sasuke (1968) and one of Kamui the Lone Ninja (Ninpo Kamui Gaiden, 1969) on the big screen. One of the primary motivations behind this site’s creation was frustration of being a product of the 80s American ninja craze and never having the superior Japanese source media of decades previous available. Now, I was seeing these anime classics in a bigger and better format than any TV-glued kid in Japan ever did.

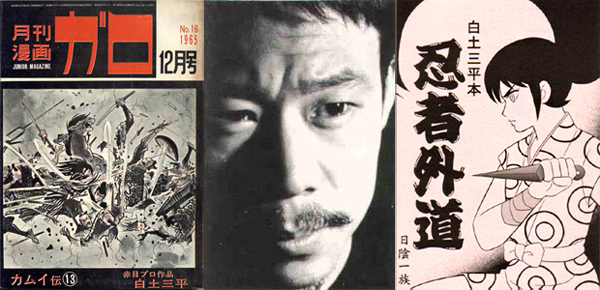

In a pre-show lecture, and post-show Q&A, Hall discussed the unique background of Sanpei — trying to live up to his father, a fine arts painter raising a son in tumultuous waters of left-wing politics and Marxist movements. (take a minute to Google some of this socio-political stuff if you want, I had to…) Somehow Sanpei comes out of it doing kamishibai performance art then manga and anime, replacing the marching proletariat with masked ninja.

Sanpei never looked to samurai or large scale feudal-era military action as a source for content of his epics, but rather redefined ninja as warriors of uncanny skill that despite living a brutal, lonely and disenfranchised existence became what millions of Japanese youth idolized. His shinobi were decidedly of the lower-class, victims of the system around them and oppression from a privileged minority above, but they had the tremendous strength and resolve to live-on as outcasts and loners — rebels even to their own kind and hunted for it. They were fantasy refuge for young kids struggling through school and office workers stuck in cubicle farms.

It also didn’t hurt that they had cool-ass exotic weapons and espionage gadgets right at the same time the James Bond movies went super-nova in popularity.

But it seems to me Sanpei was somewhat above the 60’s Japanese ninja boom. Sure, it can be argued that his Ninja Bugeicho manga, starting in the late 50s, was the compass of both editorial theme and a standard of excellence for a lot of the comics, cartoons and movies that would follow en masse, and yes, the offspring of that series — Sasuke and Kamui — were hugely popular and influential. But I think he would have created those properties regardless of whether ninja were popular mass media or not. Hall pointed out that the legendary GARO magazine that originally carried the Kamui manga, had a circulation of merely 80,000 per month, tiny compared to the more popular juggernauts that sold 4-5 million per week. GARO was a publication by artists and intellectuals for artists and intellectuals, and if the ninja explosion had never occurred he probably would have found an outlet in those niche-market pages anyway.

But ninja did explode in pop culture, and four-plus decades later are a household word on every continent, have been redefined by American exploitation cinema, again by animated turtles and then again by video games and so on and so on. Hall’s presentation had a slant of exposing the political roots of fictional ninja to audiences more familiar with Mortal Kombat and Naruto, and indeed most of those on hand were seeing the 60s craze media for the first time. There was some surprise in the audience at how layered and emotionally complex even a kids cartoon could be, and universal shock at how violent and brutal they routinely were. One of the Sasuke episodes ends with a pack of copy-cat children trying to duplicate the ninja kid’s explosive tricks, and blowing themselves to death in the process, leaving a weeping father to bury the charred corpses.

That very quality is likely what kept these series off American shelves in the 1980s, when otherwise, anything ninja was squeezed for every dollar it could yield. Both series were rife with children wielding bladed weapons, innocents being killed, bursts of hyper-violence and despondent anti-heroes walking off into the gloom of night knowing tomorrow would only bring more of the same. While Japan’s parents were evidently fine with their kids watching such after school, there’s no way that stuff was going to play in the States.

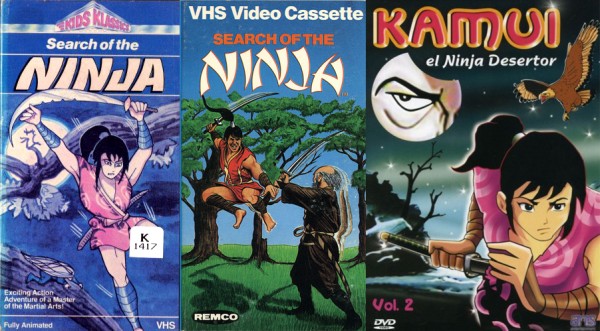

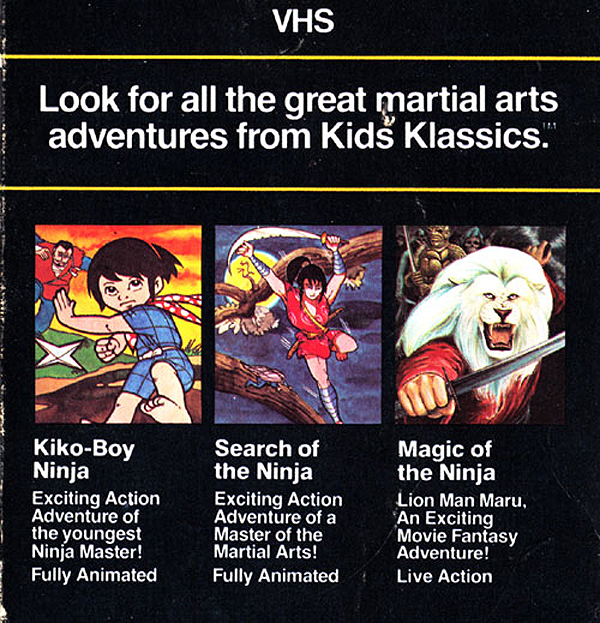

However, chunks of Sasuke and Kamui were actually licensed for release outside of Japan in the 80s. English dubs found limited priced-to-sell VHS releases under names like Kiko-Boy Ninja and Search for the Ninja, and episodes were included with Remco’s Secret of the Ninja action figure play sets. The pictures were rather wretched quality then, haven’t aged well, and will likely never see the light of day in any sort of remastered official release.

The entire run of Kamui was syndicated to TV in Mexico and South America under the title Kamui: El Ninja Desertór, and I believe both series saw the light of day in Italy as well. Then of course VIZ released The Legend of Kamui, albeit at the end of the craze. Most of us back then didn’t even realize it was a ninja comic based on the lack of black hooded assassins on the covers, plus tastes were changing. It was a good thing too late to be the ‘super-ego’ the craze had needed all along.

SO… some four decades later there we are in a packed theater, marveling at the brilliance that was Shirato Sanpei. The themes of the lone warrior fighting the good fight despite the societal machinery around him resound just as strongly. I mean, who hasn’t idly fantasized about just saying F-this to the gigantic soul-grinding world we know we can’t change, packing a sack of shuriken and living out in the woods with your pet falcon? We all have, right? Right?

Keith J. Rainville