¡Holá Amigos! The ninja craze may have been a fusion of Japanese martial and cinematic traditions filtered through American 1980s pop culture, but it spread to every civilized corner of the globe and no geographic or linguistic market was spared shuriken and ninja hoods. I myself first discovered this is the late 80s when Univisión cable aired episodes of El Fugitivo Samurai (aka the mid-70s Lone Wolf & Cub TV series) late night Saturdays and I could watch ‘Itto Ogami y Perro Hijo’ hack up ninjas in Spanish. I filled a dozen VHS tapes on SLP with that shit, grateful for swords and shinobi in any language and was infinitely grateful to the Spanish-language markets for providing that glimpse into Japanese TV we were denied in English at the time.

So let’s take a quick trip across the border and spotlight some of Mexico’s more outstanding accomplishments in the field of ninjery.

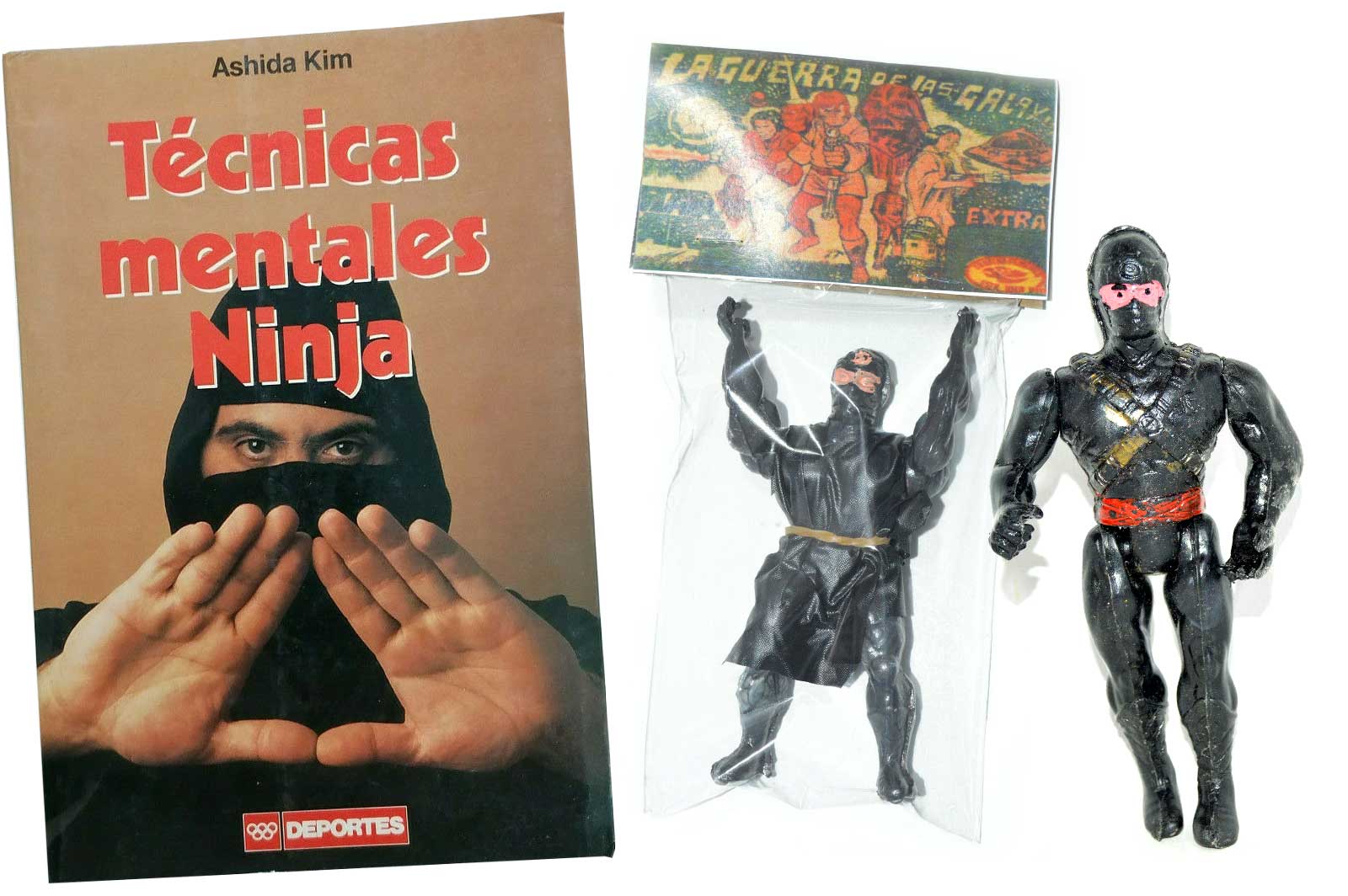

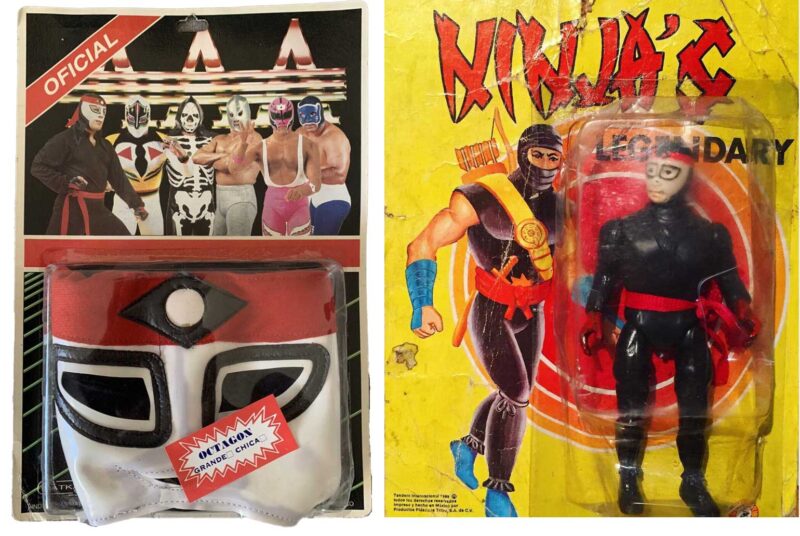

Much of our ninja craze-era output was adapted to Spanish at some point (often 5-10 years behind us, not uncommon for proliferation into Mexico regardless of genre) with the usual suspects from books, films, etc. getting Spanish editions. Bootleg ninja merchandise of a dizzying array has been produced in Mexico for the past four decades with no end in sight, and for collectors of those Turtle-things, there’s no better knock-offs anywhere.

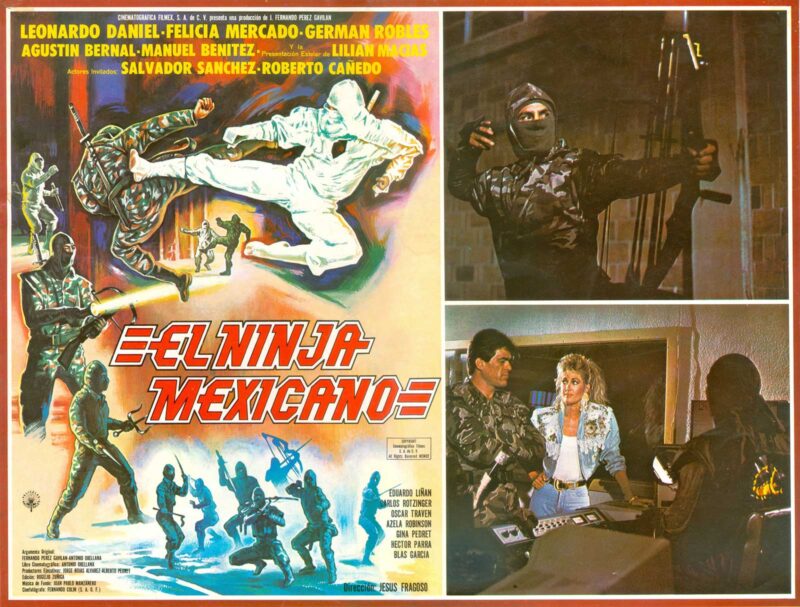

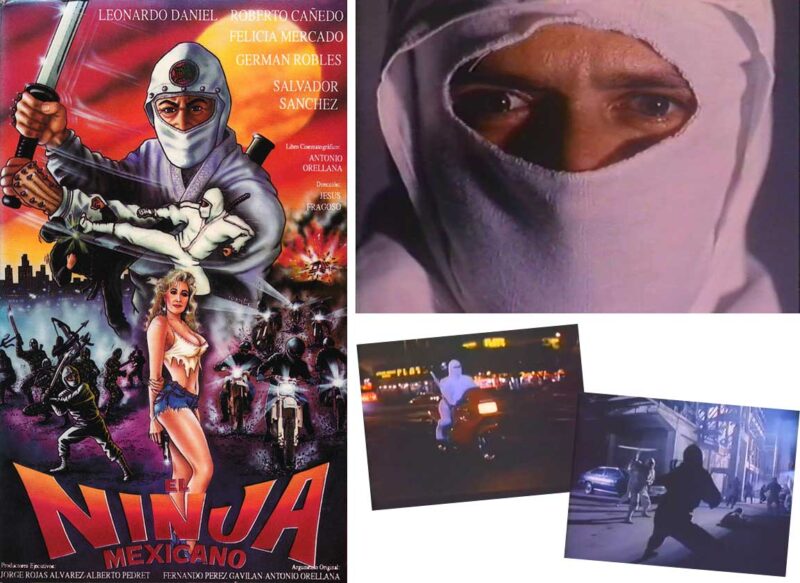

And… properly inspired by American Ninja, Mexico had it very own El Ninja Mexicano:

El Ninja Mexicano is the Ninja Mission of Mexico — a totally homegrown product cashing in on what Cannon did with Kosugi and Dudikoff — and I wish this 1991 film got the same dubbing and international release treatment its Swedish cousin enjoyed. Alas, even a guest appearance by Mexico’s famed Dracula, Germán Robles, can’t save this often too-actionless exploitation flick, but it’s certainly no worse than latter American Ninja sequels.

From a quality standpoint, I’d fairly place El Ninja Mexicano somewhere between Sakura Killers and White Phantom at best, with lower moments swinging towards the IFD/Filmmark realm. But my overall feeling when watching it always Why the hell didn’t this get dubbed and exported?!?!

Sadly, there’s no readily available good release of this, but at the moment it’s available online here.

El Ninja Mexicano is certainly a by-product of Cannon films and episodes of The Master being released on Spanish-dubbed VHS and hitting Mexican TV, so it’s late to the party and lacks the energy of the early craze.

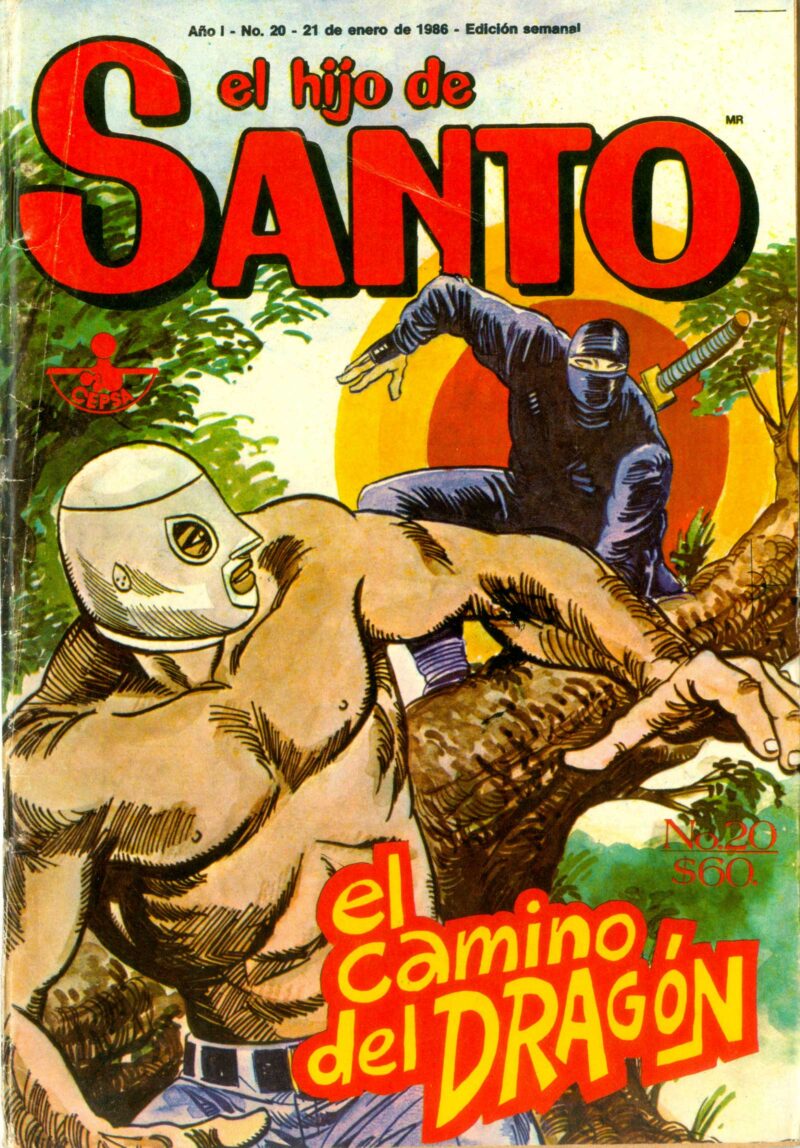

More contemporary to the boom going on in the U.S. was this crossover with Mexico’s most famous multi-media superhero:

For the uninitiated, El Santo was the Elvis of Mexican wrestling (lucha libre), selling out arenas all over the Spanish-speaking world in the 1950s, starring in a photo-collage format comic book series that sold millions of copies a week, then seamlessly transitioning to action films where as himself he fought everything — vampires, mummies, frankensteins, aliens, blobs, time travelers, zombies, axe murderers, evil spies, crime lords and more. Retiring in the 80s, he passed the family’s trademark silver mask to his son who picked up all said multi-media mantles, including this illustrated comic that cashed-in on the ninja boom. In terms of Mexico, the ultimate stamp of cool on a foreign fad was for El Santo to validate it.

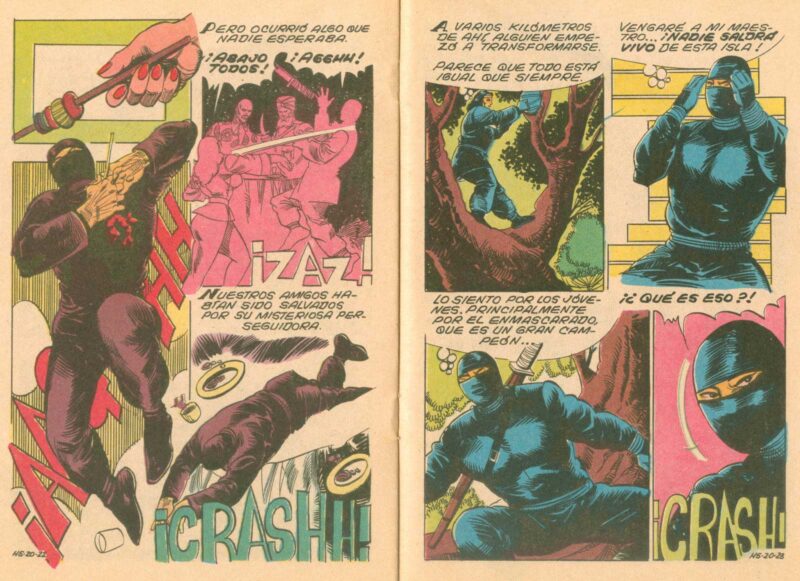

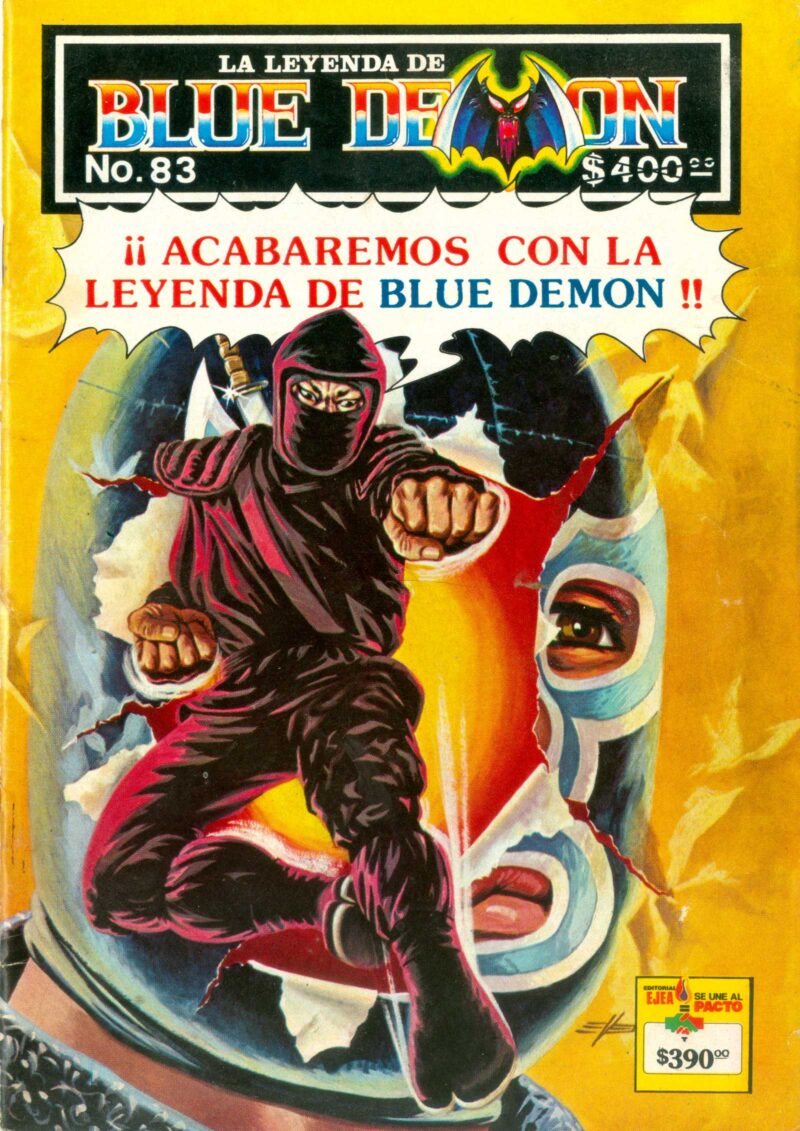

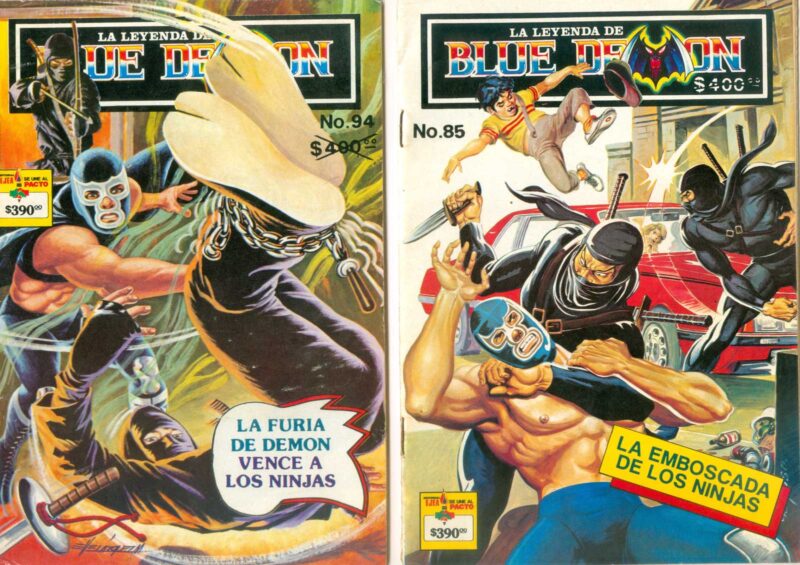

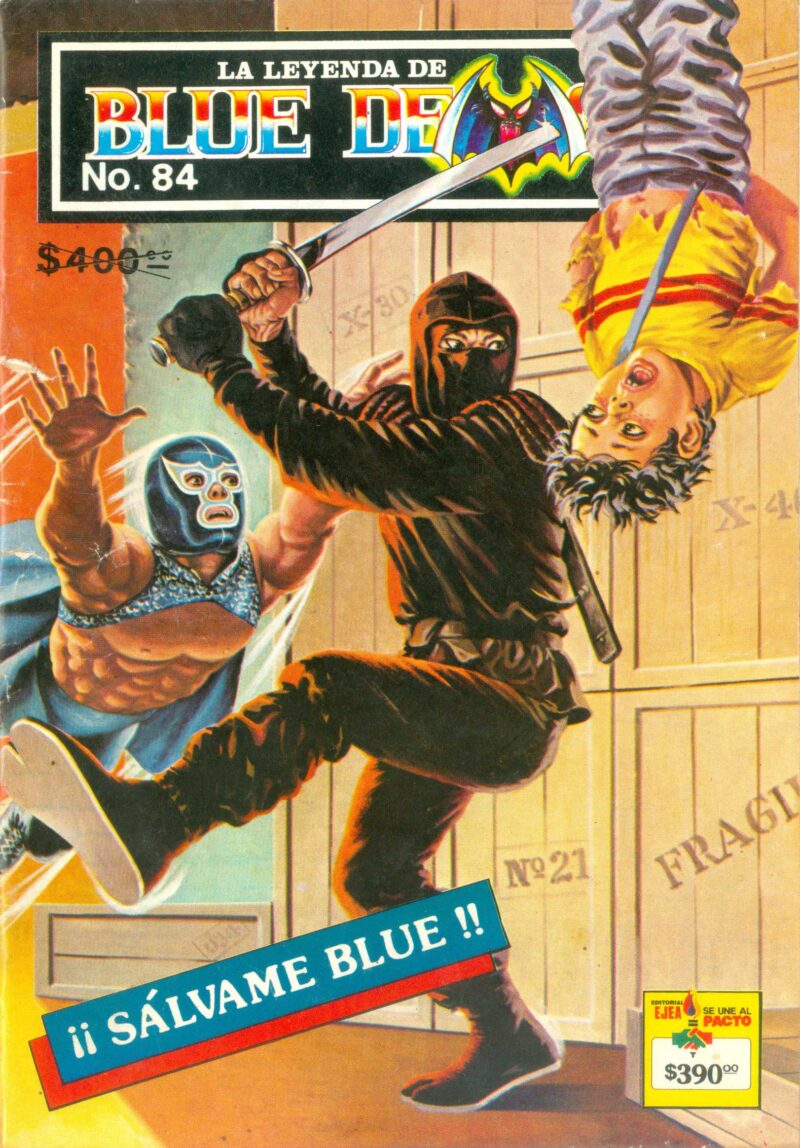

If Santo was Mexico’s Superman, Blue Demon was its Batman.

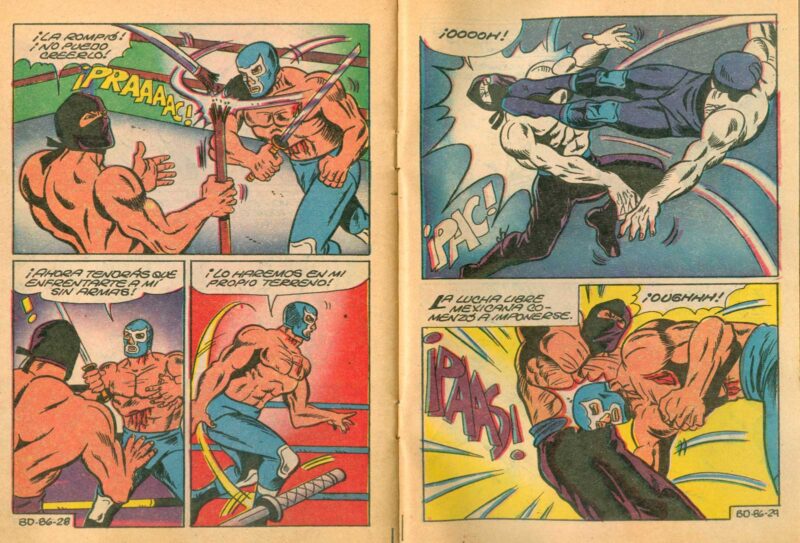

This rougher, arguably tougher, grappler was both rival and partner to Santo for decades, and also passed down the family mask to an heir who took it into comics. Demon had a significant run of comic issues dedicated to warring ninja clans encroaching into Mexico.

Some pretty classic ninja action here, with no shortage of violence and some rather jaw-dropping child endangerment on hand!

The point of adventures like this was always to import an exotic foreign threat, but ultimately prove that good old homegrown lucha libre was the ultimate martial art.

Some luchadores, rather than battle their practitioners, embraced the martial arts themselves. They took the masked wrestler idiom of lucha libre and fused it with martial arts costuming and training gear, creating a phenomenally popular hybrid of Mexican ring tradition and Asian martial and movie arts.

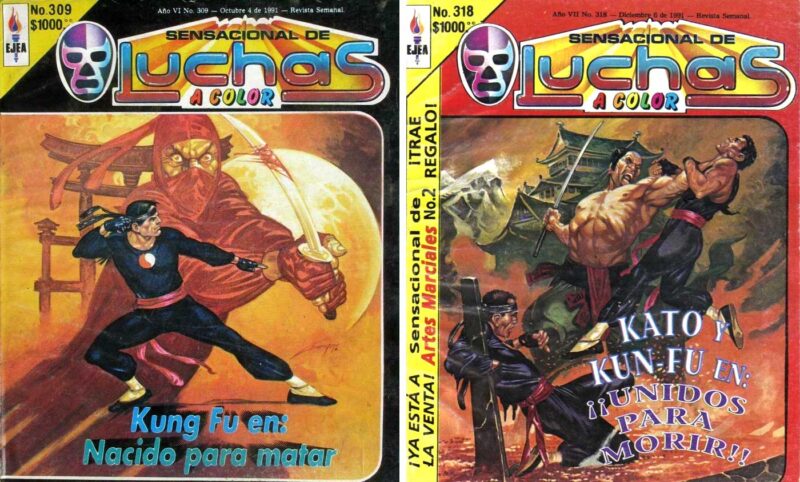

Going all the way back to Bruce Lee, martial arts-themed masked wrestlers — often allegedly stars imported from Asia but more often than not just local talent mimicking the movies they saw — were an absolute sensation in Mexican rings. Kato Kung Lee, Kung Fu and Blackman rocked the satin kung-fu gear and set the trend for decades with that look. Super Kendo was a chip off the old block. Takeda had a somewhat cringe-worthy mask that mimicked a Japanese caricature.

And like many other colorful ring characters, the squared circle was only the beginning of their exploits…

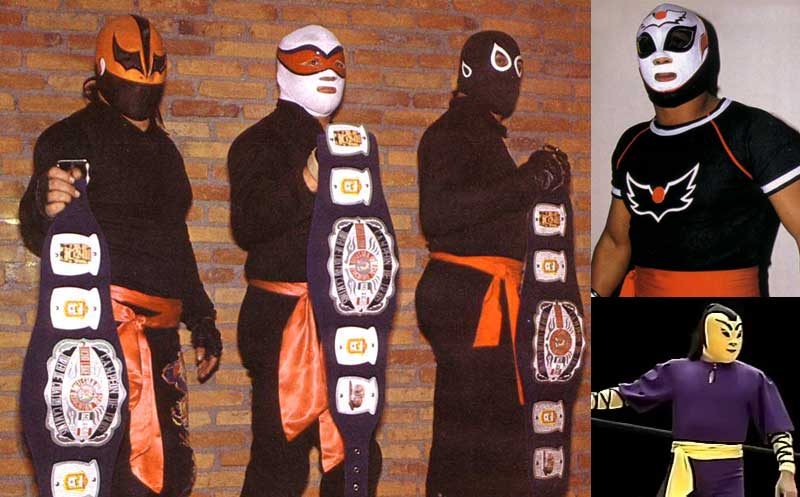

But the apex of Mexico’s martial-masked-men was an absolute product of the American ninja craze — Octagón!

Antonio Peña was a visionary promoter who looked at where 1980s wrestling had gone in the States — mega glitz and glam, over-the-top muscle men and outré characters galore — and saw potential to upset the apple cart of Mexico’s largely tradition-laden and conservative wrestling industry. Colorful as lucha libre had always been, he took his product up a notch and embraced MTV-like television production and glommed onto anything cool and foreign he could, 80s ninja being an easy pick.

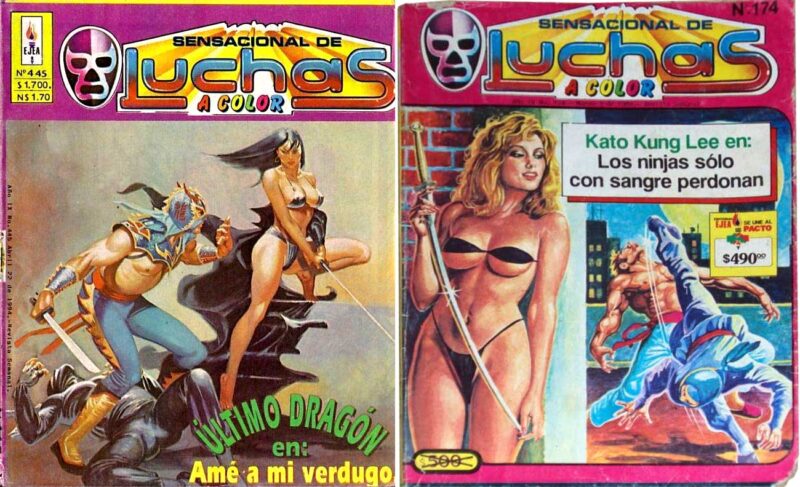

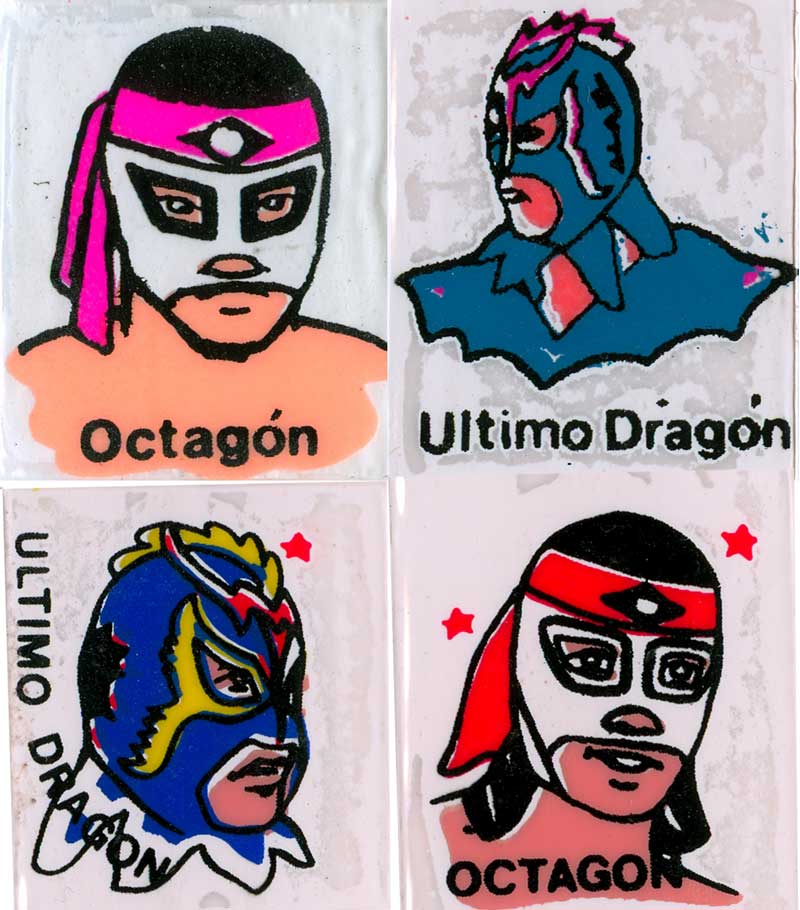

Peña was a character creator par-excellence, fostering the Bruce Lee homage El Ultimo Dragón and the outright ninja-knock-off Octagón.

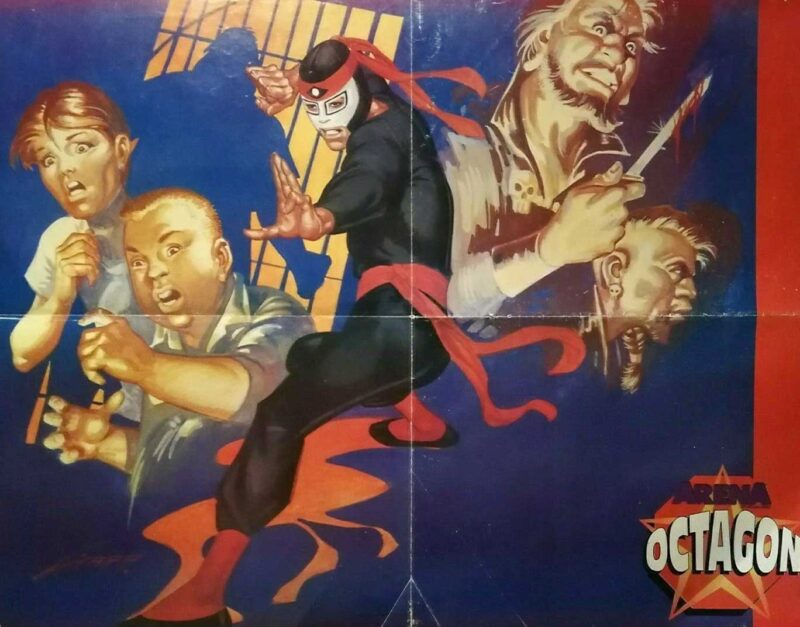

The man under the Octagón mask had some martial arts background — certainly enough to throw some convincing kicks and kata-like posing — and his wrestling skills and athleticism were first rate too. He became an instant sensation and would go on to be one of if not the most marketed and merchandised ring stars of the 1990s.

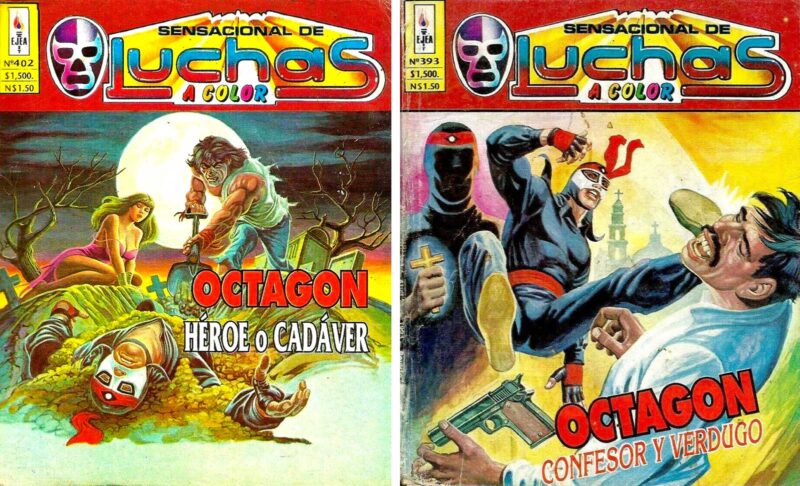

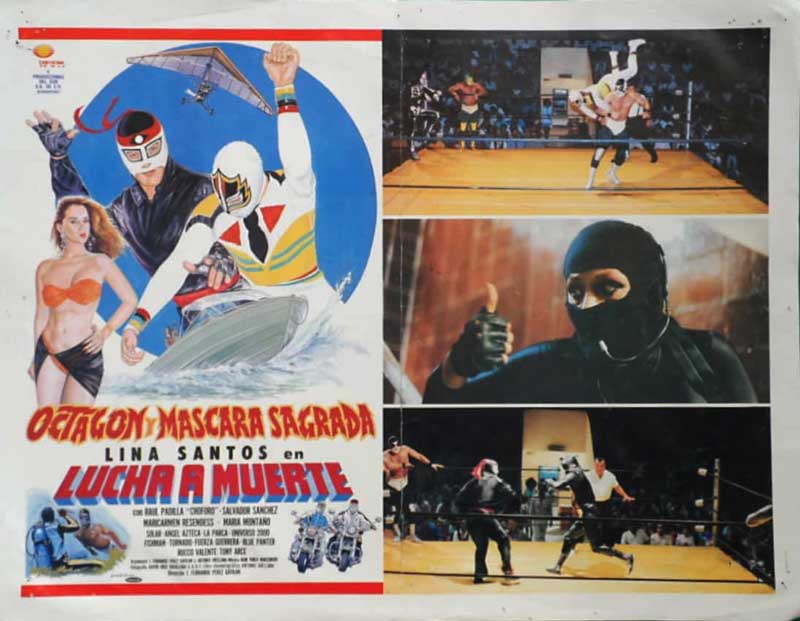

Octagón also starred in three movies, paired with other champion luchadores, in which he always had at least one honest attempt at a full-on martial arts fight. These were nowhere near your average Shaw Bros. flick in terms of choreography or execution, but for kids in Mexico he was karate god.

While Ultimo Dragón would go on to fame in the U.S. and return to his Japanese roots, Octagón remained a huge star in Mexico, eventually feuding with evil doppelgänger Pentagón (a gimmick-descendant of which is current AEW sensation Penta El Zero Miedo albeit with more of a Mortal Kombat than 80s ninja boom influence), and there is currently an Octagón Jr. to perpetuate the lucha-ninja lineage.

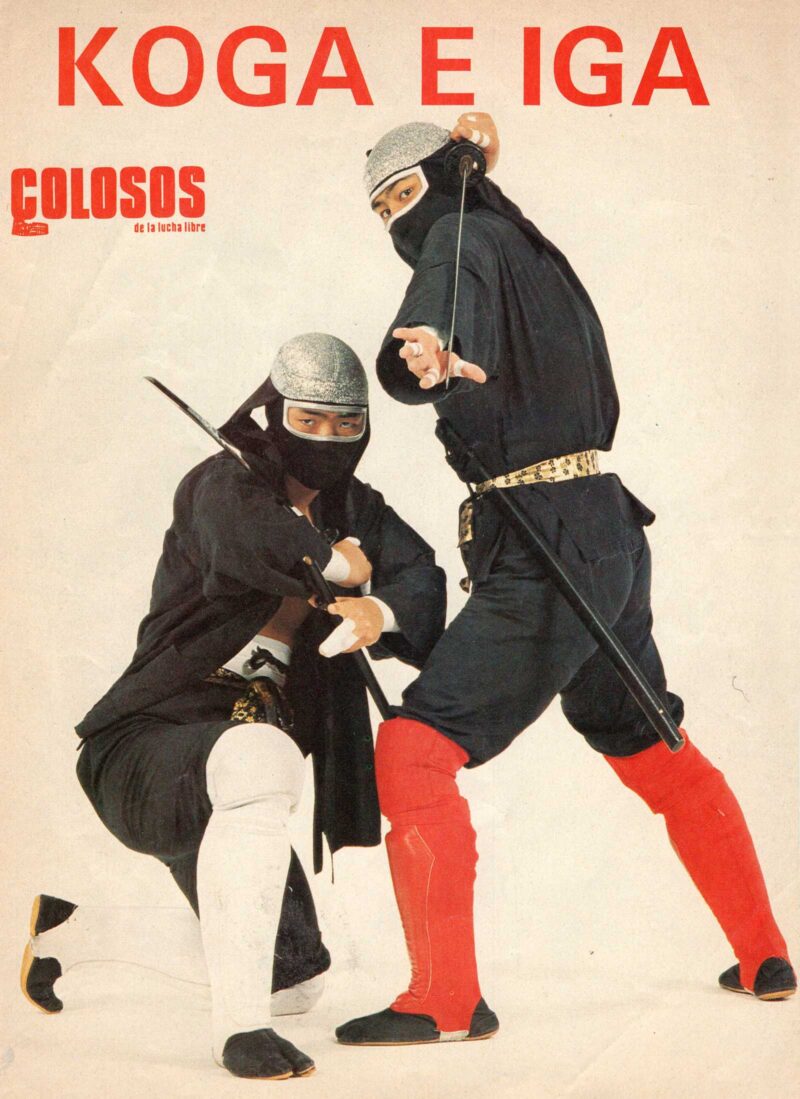

My personal all-time favorite lucha-ninjas were two rookie Japanese wrestlers sent to Mexico to gain experience in the 90s (I’ve found conflicting info as to their real identities). They embraced their roots and became two outright ninja — Koga and Iga. Their run was short-lived and is merely a footnote in lucha history, but they were probably the most legit outright ninja characters Mexican rings ever saw.

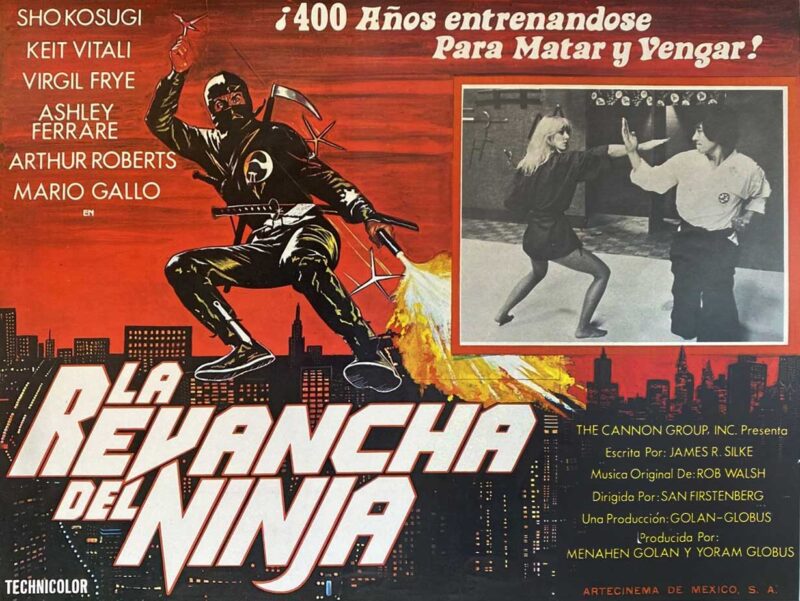

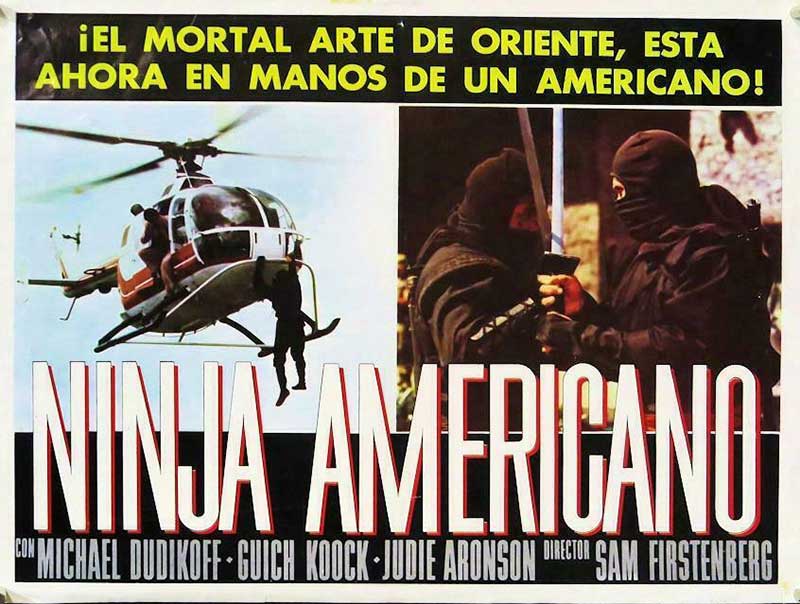

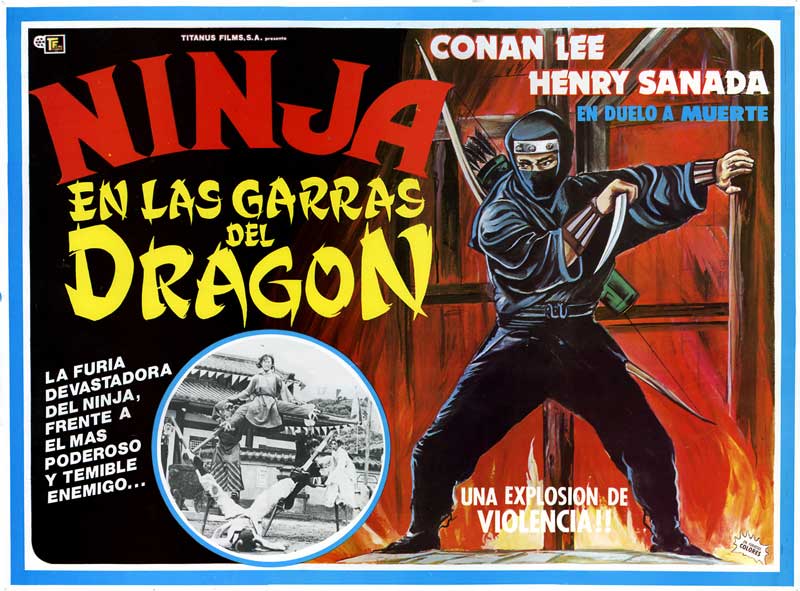

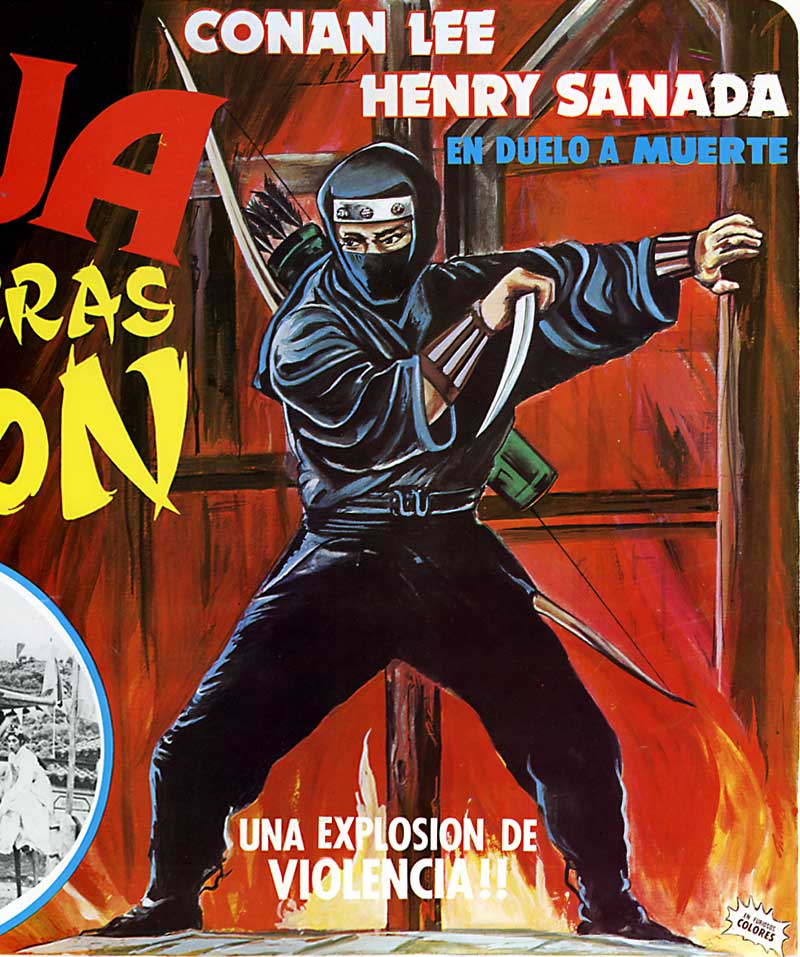

But if you’re not a wrestling fan, nor a comics reader (sorry, I cannot relate), collecting the Mexican versions of international ninja movie ephemera can be a real blast. There’s always some variant photo you’ve never seen before, and sometimes outright new art unique to the Spanish-language marketing campaigns.

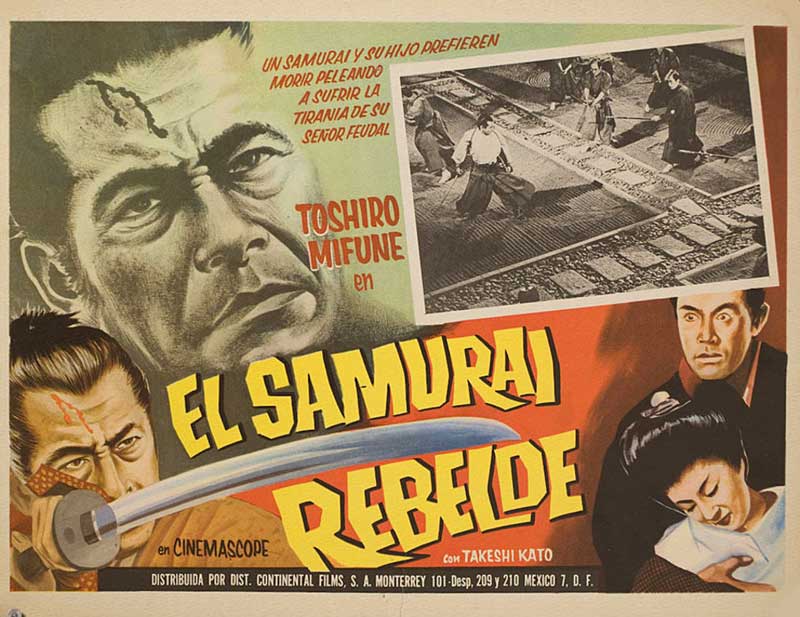

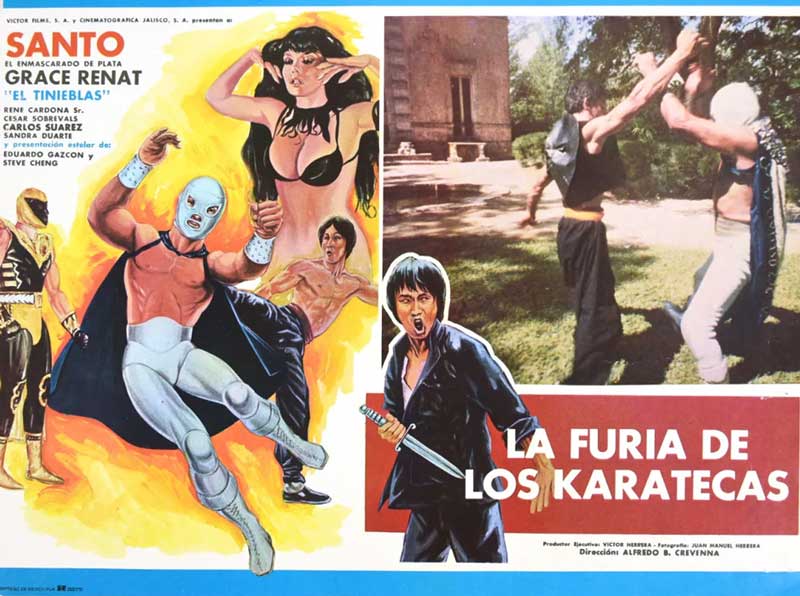

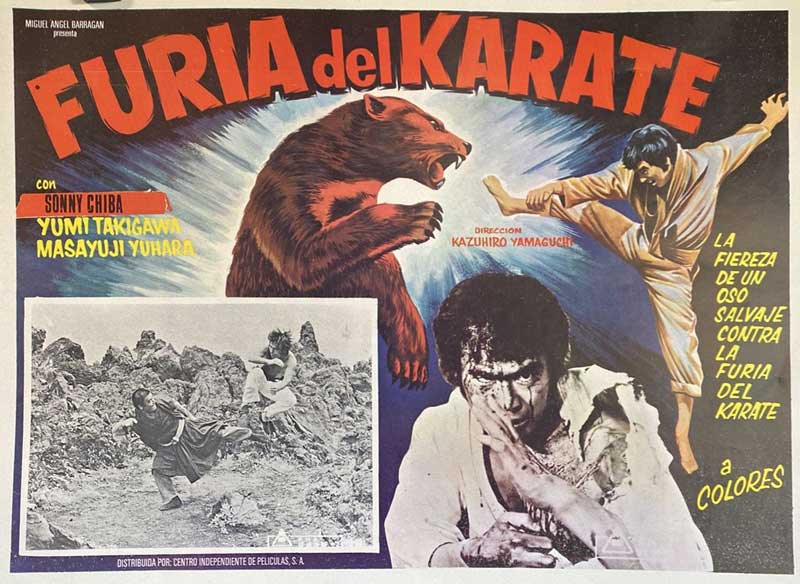

Tangental, if you collect any realm of martial arts posters, there’s always some curious mutation to be found in Mexican markets:

So whether it is the completist in you hunting down variant movie posters, the curious collector wanting to see what’s behind those lush and lascivious comic book covers, the wrestling fan who never knew Great Kabuki-like action was always happening down South, archeologists of horrendously bad knock-off action figures, or that movie hound who needs to see every ninja movie ever, there are plenty of shadow-y corners of old Mexico to explore! And f’n amazing street tacos… god I’m hungry…

Keith J. Rainville — August, 2022